Summary by James R. Martin, Ph.D., CMA

Professor Emeritus, University of South Florida

Capital Markets Main Page |

Organization Structure Main Page

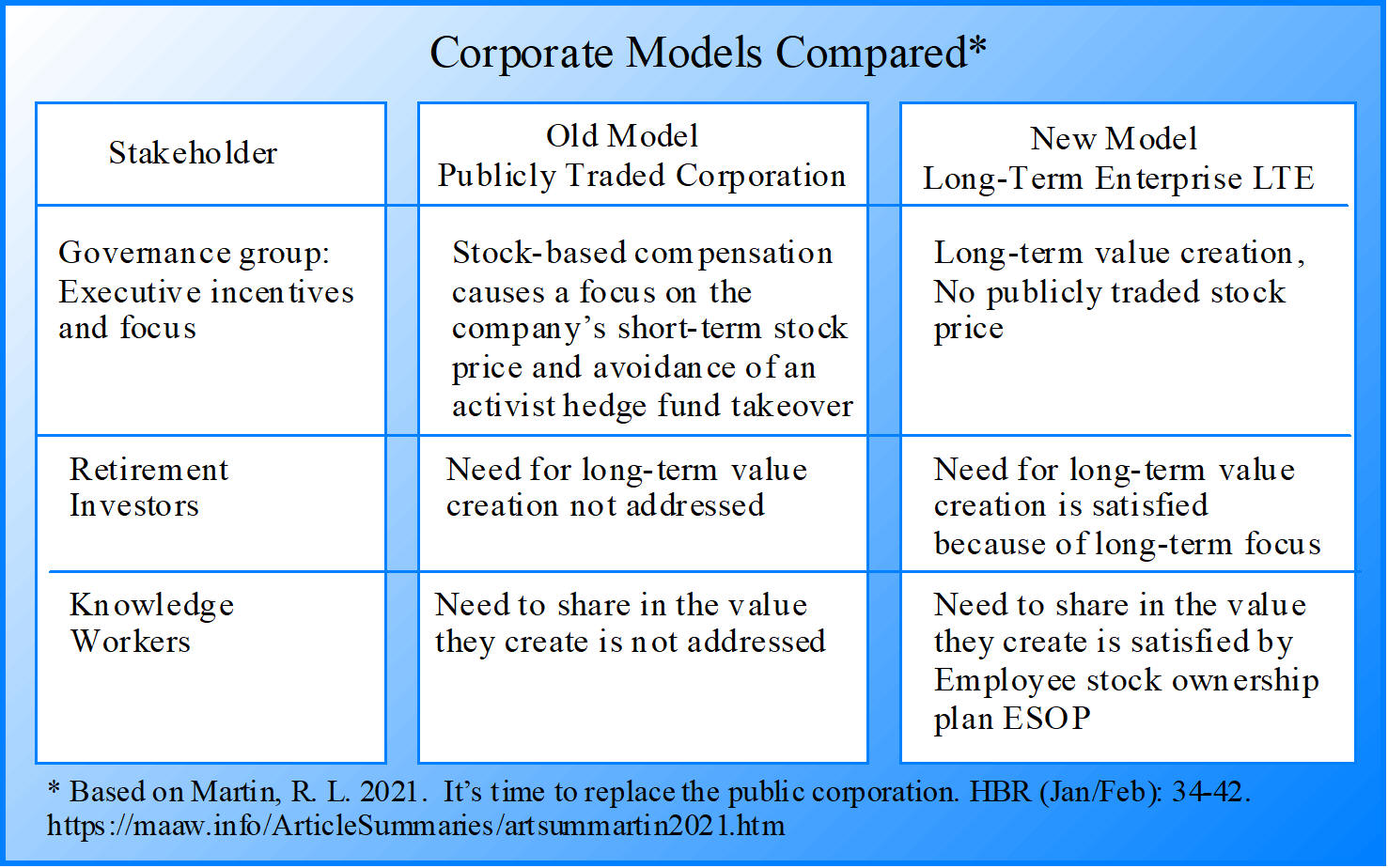

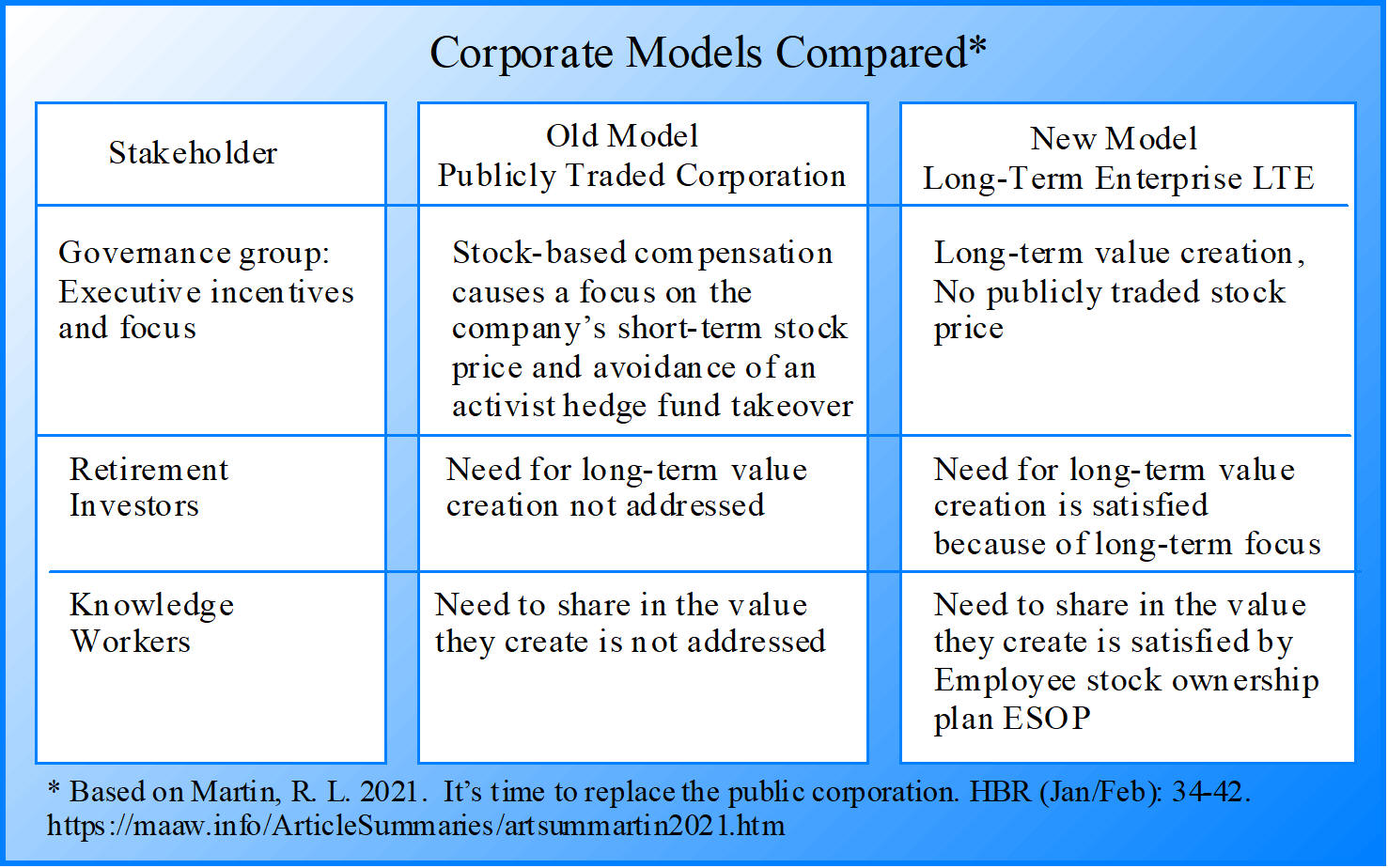

The purpose of this article is to track the decline of the professionally managed, publicly traded corporation, explain why it no longer serves the needs of critical stakeholders, and present a new model that could displace the public corporation as the dominant structure in business.

The current public corporation model developed in the wake of the Great Depression and has been the dominant structure for the past 100 years. It was an effective way to mobilize capital from private investors, but in more recent years the model has provided the incentives for executives to focus on short-term gains to enhance their stock-based compensation, and attempt to avoid activist hedge fund takeovers.

The Turning of the Tide

As early as the 1970's critics argued that professional managers were imperfect agents because they were inclined to maximize their own welfare rather than that of the shareholders. Stock-based compensation was developed as a solution, and this triggered an explosion in stock and stock-option grants over the following years. Unfortunately, the emphasis on stock-based compensation caused executives to focus on short-term movements in the firm's stock prices rather than long-term value creation. Corporate raiders amplified the effect of these trends providing executives with an additional incentive to focus on the company's stock price. Some executives have even engaged in fraud to boost their stock price. This resulted in a number of accounting scandals in 2001 and 2002, e.g., Enron, Adelphia, Global Crossing, WorldCom, and Tyco.

The Failure of the Public Corporation

There have been attempts to improve the governance of public corporations, e.g., the 2002 Sarbanes-Oxley Act, but these attempts to solve the problem have not addressed the underlying cause. The root of the problem is that public corporations no longer serve the interests of their most important stakeholders, i.e., retirement investors and knowledge workers. Today, people saving for retirement make up the largest group of investors. These investors typically have a very long-term outlook with the goal of high long-term returns for retirement income. But executive incentives are not consistent with the retirement investors long-term goal of value creation. On the other hand, knowledge workers who are the primary driver of a company's value are asked to work for the benefit of its shareholders. They are expected to make sacrifices to satisfy executives' whose welfare is determined by the company's stock price, and in the interest of stockholders who no one knows.

A New Model - The Long-term Enterprise or LTE

Private equity ownership might appear to be a candidate to replace the publicly held corporation. Its growth has been fueled by the major pension funds, but private equity is not a substitute for public corporations because it is based on their existence. PE funds must sell the companies they buy within a five to seven year period to turn their investments into cash. If public corporations and capital markets did not exist, PE funds would not exist.

Finding a model to displace the public corporation requires an understanding of the needs of knowledge workers and retirement investors. A new model must overcome the governance problems that CEO's incentives conflict with the long-term interest of those stakeholders, and the ability of activist hedge funds to extract gains at their expense. The author's recommended model is referred to as the long-term enterprise or LTE, a private company where ownership is limited to the stakeholders with the greatest interest in long-term value, i.e., retirement investors and employees.

A long-term enterprise would include an employee stock ownership plan (ESOP) and partner with one or several pension funds to acquire the company and take it private. Since there would be no stock price, governance would focus on long-term performance rather than short-term stock price fluctuations. Employee stock ownership plans would also provide knowledge workers with a much needed long-term stake in the company. An example is provided by Publix Super Markets that is 100% owned by an ESOP. Other large supermarkets that have ESOPs include WinCo Foods, Brookshire Brothers and Metcash. Others outside retail include W.L. Gore & Associates, the creator of GoreTex, Graybar, a distributor of electrical, communications and data-networking products, and Gensler an architectural firm. Many of the largest companies with ESOPs are either retailers, or professional firms focused on architecture, engineering, or consulting.

An employee stock ownership plan is not equivalent to an employee retirement plan because employee retirement plans should not be wholly or largely invested in company stock. An ESOP is instead a way to reward and motivate employees to create value. Ownership shares would vest after six years and a third party would establish the fair value of those shares when an employee leaves so that the shares could be bought by the plan at a fair price. Retiring employees would roll the proceeds into their retirement accounts.

The long-term enterprise or LTE model would satisfy the primary needs of both retirement investors and knowledge workers without removing any of the advantages of the public corporation's structure. The focus for both executives and employees would be on creating long-term value rather short-term results to influence the company's short-term stock price.

__________________________________________

Related summaries:

Collingwood, H. 2001. The earnings game: Everyone plays, nobody wins. Harvard Business Review (June): 65-74. (Summary).

Dechow, P. M. and D. J. Skinner. 2000. Earnings management: Reconciling the views of accounting academics, practitioners, and regulators. Accounting Horizons (June): 235-250. (Summary).

Healy, P. M. and J. M. Wahlen. 1999. A review of the earnings management literature and its implications for standard setting. Accounting Horizons (December): 365-383. (Summary).

Healy, P. M. and K. G. Palepu. 2003. How the quest for efficiency corroded the market. Harvard Business Review (July): 76-85. (Summary).

Porter, M. E. and M. R. Kramer. 2011. Creating shared value: How to reinvent capitalism and unleash a wave of innovation and growth. Harvard Business Review (January/February): 62-77. (Summary).

Schilit, H. 2002. Financial Shenanigans: How to Detect Accounting Gimmicks & Fraud in Financial Reports. 2nd edition. McGraw Hill. (Summary).

Waddock, S. 2005. Hollow men and women at the helm ... Hollow accounting ethics? Issues in Accounting Education (May): 145-150. (Summary).