Chapter 1

Introduction to Managerial Accounting, Cost Accounting and Cost Management Systems

James R. Martin, Ph.D., CMA

Professor Emeritus, University of South Florida

MAAW's Textbook Table of Contents

After you have read and studied this chapter, you should be able to:

1. Explain the difference between conceptual definitions and

operational definitions.

2. Provide conceptual definitions for public accounting, management accounting

and governmental accounting.

3. Discuss the various components of management accounting and relate them to

the focus of this textbook.

4. Explain the importance of recognizing the interactive relationships between

systems, performance measurements, human behavior and variability.

5. Discuss the concept of control.

6. Discuss the relationship between the matching concept and cost accounting.

7. Provide conceptual definitions for some basic cost terms such as

manufacturing costs, selling and administrative costs, variable costs, fixed

costs and mixed costs.

8. Discuss two global variants of capitalism in terms of the major concepts and

assumptions underlying the economic system.

9. Explain how the major business concepts, attitudes and practices differ for

the two global variants of capitalism discussed in learning objective 8.

10. Discuss why the two global variants of capitalism provide an important

underlying framework for the study of management accounting and related

management concepts.

Although bookkeeping can be traced back to the thirteenth century, accounting historians place the origin of management accounting around 1812. Around this time, textile mills began to perform many processes inside the organization that had previously been performed outside the company by independent craftsmen.1

This internalization of processes such as spinning, weaving and assembly created a need for determining the cost of performing these activities inside the company. From this modest beginning, management accounting has evolved into a dynamic and extremely important, although controversial part of business and economics. As a result, this discipline provides a great many opportunities for students who seek careers in accounting and other areas of management. The purpose of this book is to help you develop an understanding of the concepts, techniques and controversial issues associated with what most accountants refer to as cost and managerial accounting. Although your initial perception of this course may be somewhat different, this is a very broad discipline with rich conceptual linkages to economics, finance, statistics, production management, management science, marketing and engineering. If you pursue it diligently, this course of study will become an invaluable experience regardless of your particular career path.

The purpose of this chapter is to introduce the concepts that provide a foundation for our excursion into the domain of cost and managerial accounting. More specifically, the objectives are to: 1) discuss the difference between conceptual definitions and operational definitions, 2) provide conceptual definitions for the three broad specialty areas of accounting including public accounting, management accounting and governmental accounting, 3) outline the components of management accounting to identify the focus and scope of this book, 4) discuss the interactive relationships between systems, variability, performance measurements and human behavior, 5) define and discuss the concept of control, 6) present some basic terminology, and 7) introduce an underlying framework for the study of management accounting concepts and techniques.

CONCEPTUAL VERSUS OPERATIONAL DEFINITIONS

Before proceeding to the various definitions presented below, it is useful to consider two types of definitions: 1) conceptual definitions and 2) operational definitions2. Conceptual definitions are those typically found in a dictionary and usually represent generalizations. On the other hand, operational definitions are very specific. Operational definitions contain sufficient clarity so that they cannot be misinterpreted. Therefore, conceptual definitions and operational definitions are on opposite ends of a continuum. For example, a conceptual definition of clean is "free from dirt." We might say, the carpet is clean after vacuuming and a visual inspection. But suppose we are talking about cleaning the instruments needed for brain surgery. Then we will need an operational definition. Another more relevant example in the area of accounting is the term "net income". Conceptually, net income is defined as the difference between revenues and expenses, but this is just a generalization. Net income has no operational meaning until we know precisely how revenues and expenses are measured3. In fact, one accounting researcher calculated that there were over thirty million ways to calculate net income based on the number of combinations of generally acceptable accounting alternatives (Chambers, 19664). This distinction between conceptual definitions and operational definitions will help us avoid some confusion while we are building an understanding of the discipline.

The definitions presented in this chapter are conceptual definitions. However, as we move through this textbook, we will use these concepts to define and integrate the components of accounting more specifically. In other words, the conceptual definitions in this chapter provide a foundation for building operational definitions in later chapters.

Accounting is made up of several specialty areas that might be defined in a variety of ways. Generally, there are three broad areas of accounting that include public accounting, governmental accounting and management accounting. These specialty areas are illustrated in Exhibit 1-1 and discussed individually below.

PUBLIC ACCOUNTING

Public accounting, although the most familiar area of accounting to the general public, is a relatively narrow part of accounting that places major emphasis on auditing general purpose financial statements, i.e., income statements, balance sheets, and cash statements. Certified public accountants (CPA's) also provide tax and other types of advisory services to their clients, but this is still rather narrow when compared to the whole range of activities performed in the accounting discipline. Although important, public accounting is outside the scope of this textbook.

GOVERNMENTAL ACCOUNTING

Governmental accounting is non-accrual accounting5 used to account for governmental agencies, and nonprofit seeking organizations such as state universities. It is completely different from the material studied in financial and managerial accounting courses and is also outside the scope of this textbook.

MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING

Management accounting is the broadest area of accounting and includes tax accounting, financial accounting, managerial accounting and internal auditing.6 Each of these areas is discussed below and illustrated in Exhibit 1-1. Management accounting is expanded in Exhibit 1-2 to include cost accounting, cost management, activity management and investment management. The concept definitions and relationships between these branches of management accounting are also discussed below. The CMA designation that appears in the exhibits represents "certified management accountant". The requirements for obtaining this professional credential are outlined in an appendix to this chapter.

Tax and Financial Accounting

Tax accounting and financial accounting both involve generating financial reports for external users, although the two reports may be very different. Tax returns are required for reporting to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and must conform to a specific set of rules. Financial accounting, on the other hand, involves preparing general purpose financial statements for stockholders and creditors. In addition, a family of K-statements (e.g., 8K, 10K) are prepared for the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Financial accounting statements must conform to generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). This requirement causes external financial statements to be of limited usefulness for internal purposes. The previous statement is not meant to be a criticism of external financial statements, but merely to recognize that different audiences (e.g., stockholders, creditors, plant managers) need different types of information. Internal statement users tend to need more timely, less aggregated information than external statement users. The specific requirements of GAAP and the SEC are outside the scope of this textbook.

Internal Auditing

Internal auditing is an area of accounting that is mainly concerned with the organization's internal control system. Internal auditors may examine, or audit, all of the organization's accounting and management systems. Although internal auditing is an important area in accounting, it is also beyond the scope of this text.

Managerial Accounting

Managerial accounting and the connecting branches highlighted in Exhibit 1-2 provide the focus of this textbook. As indicated in the exhibit, managerial accounting is linked to cost accounting, cost management, activity management and investment management. Managerial accounting involves generating information for internal users including all levels of management and others within the organization. Some of the same information is reported that appears in the external financial statements, but frequently the information provided to internal users is in more detail, provided more often, and in many different forms depending on how the information is to be used. A key difference between financial accounting and managerial accounting is that managerial accounting reports are not directly constrained by GAAP.

Cost Accounting

Cost accounting is linked to tax accounting, financial accounting and managerial accounting in Exhibit 1-2 because it is an important component of each discipline. Why? Because cost accounting involves determining the cost of something, such as a product, a service, an activity, a project, or some other cost object. These costs are needed for several purposes. For example, the costs of products and services produced and sold are needed for both tax and external financial statements. In other words, tax and financial accounting depend on cost accounting to provide cost information. Information about costs is also needed for a variety of management decisions. For example, cost estimates are needed to determine whether or not a product or service can be produced and sold at a profit. Unit costs of a product (or service) are also needed for product pricing and product discontinuance decisions. In addition, accurate cost information is required to determine whether or not a company should make (produce) or buy the raw materials, parts and subassemblies that become part of its major products and services. From this perspective, cost accounting is perhaps underrated as a discipline since none of the other disciplines including tax accounting, financial accounting or managerial accounting could exist without cost accounting.

Cost Accounting’s Changing Emphasis

Prior to 1950, cost accounting courses emphasized generating cost information for tax and financial accounting purposes. These courses had a fairly narrow orientation towards inventory valuation for external reporting. However, in 1950 a textbook by William Vatter placed more emphasis on the internal user of accounting information, rather than the external user.7 After 1960, most cost accounting textbooks had a distinctive managerial decision orientation. Vatter’s work was definitely a turning point. Two other very influential books, although they are not textbooks, were published in 1987 and 1988. These works include Relevance Lost: The Rise and Fall of Management Accounting by H. Thomas Johnson and Robert S. Kaplan and Cost Management for Today’s Advanced Manufacturing edited by Callie Berliner and James A. Brimson.8 These two books represent another turning point for management accounting. Both publications sharply criticize traditional accounting and propose substantial changes in internal accounting systems. These important publications introduced the concepts of cost management, activity management and investment management that have become important components of management accounting.

Cost management is a term that has been popularized by CAM-I (Consortium of Advanced Management - International).9 Cost management is said to be a more comprehensive concept than cost accounting in that the emphasis is on managing and reducing costs rather than reporting costs.10 In other words, it is a long run proactive approach rather than a short run reactive approach. For example, a great deal of attention is given to reducing costs at the design stage of a product's life cycle rather than simply attempting to measure and control cost during the production stage. James Brimson, who originally served as CAM-I's Cost Management Systems (CMS) project director, defines cost management as, "the management and control of activities to determine an accurate product cost, improve business processes, eliminate waste, identify cost drivers, plan operations, and set business strategies.11 Based on Brimson's definition, the concept of activity management is part of the cost management discipline originally defined by CAM-I, although the term cost management might be interpreted differently as indicated below.

Activity management, or activity based management, places emphasis on continuously improving the activities and tasks, or work that people perform in an organization. The main idea is to find and eliminate waste. Conceptually, activity management is somewhat different from cost management in that it focuses on the waste itself, not the cost of waste.12 It is a process oriented approach rather than an accounting results oriented approach. Activity management also has a long run, rather than a short run emphasis. Although activity management is part of the cost management system (CMS) advocated by CAM-I, it is important to make a distinction between managing costs (accounting results) and managing activities (processes or work). This distinction is important because placing too much emphasis on costs (or any other short run results oriented measurement) may cause managers to make decisions that reduce costs, but are not in the best interest of the organization's long run performance and competitiveness. A few examples include a manager's decision to reduce research and development, employee training, and preventive maintenance just to improve short term accounting results. This conceptual distinction provides the reason cost management and activity management are presented as separate concepts in Exhibit 1-2.

Investment management involves the planning and decision process for the acquisition and utilization of an organization's resources, including human resources as well as technology, equipment and facilities. The concept of investment management includes the capital budgeting discounted cash flow methods traditionally studied in accounting and finance courses, but is more comprehensive in that the organization's portfolio of interrelated investments is considered as well as the projected effects of not investing. Investment management is more of a holistic concept than capital budgeting in that it considers the effects of an investment decision on the entire organization rather than simply the local areas such as individual departments or individual divisions where the investments are made.

SYSTEMS, PERFORMANCE MEASUREMENT, BEHAVIOR AND VARIABILITY

A system has been defined as "a group of interacting, interrelated, or interdependent elements forming or regarded as forming a collective entity".13 A performance measurement system is part of an overall system, (i.e., it is a subsystem) because it not only measures performance within the system, but simultaneously affects performance within the system. Performance measurements are interacting, interrelated or interdependent elements within the system.

THE DUAL PURPOSE OF ACCOUNTING MEASUREMENTS

The realization that accounting is part of the system helps one understand why accounting measurements must have a dual purpose that includes influencing behavior14, or performance, as well as measuring performance. Management accounting is a powerful method of influencing behavior because, in many organizations, much of the information that is used to evaluate performance is generated by the management accounting systems briefly described in the preceding sections. The manner in which segments of a company (departments, plants, divisions, product lines, managers, and workers) are evaluated has a very strong influence on behavior. Thus, it is important for those who develop and use performance measurement systems (or subsystems) to understand the overall system and the interactive nature of the company’s performance measurements. It is also important that developers and users of performance measurement systems understand the concept of variability and the tools of measuring variation within a system.

Walter A. Shewhart, and more recently W. Edwards Deming, explain that there are two types of variation within a system.15 These include variation that results from common causes and variation that results from special causes. Variation that results from common causes is attributed to the faults or randomness of the system, while variation caused by special causes might be attributed to a particular worker, group of workers, a specific machine, or some local condition. Deming estimated that ninety-four percent of the variation within a system is attributable to common causes, i.e., problems caused by the system itself, although most of the blame is placed on the people working in the system.

Control relates to the concept of variability briefly discussed in the section above. An understanding of the concept of control requires the realization that there will always be variation in any cost or process measurement. Generally, control refers to influence over an outcome and involves an evaluation to determine if the object to be controlled, such as a cost, or process measurement, is inside or outside an acceptable range, i.e., whether it is considered to be "in control", or "out of control". A cost (or process measurement such as a quantity of input) that is outside the acceptable range, is viewed as potentially out of control. This condition may require an investigation to determine the cause of the problem. Then, if the cause can be determined, some action may be taken to correct the situation. The control procedure is the basis for management by exception which is a key concept in the business world.

Control Charts

The acceptable range referred to above may be established intuitively, (not recommended) or by using a tool referred to as a statistical control chart. Although intuition is not a reliable way to establish control limits, the statistical control chart is based on the work of Shewhart and the concepts of common (or random) causes and special (or assignable) causes. Observations that are plotted within the statistical control limits on the chart are attributed to common causes, i.e., variation caused by the system, while observations that are plotted outside the control limits are attributed to special causes that may need to be investigated. Further discussion of the control concept is provided in subsequent chapters.

THE MATCHING CONCEPT AND COST ACCOUNTING

The costs associated with a manufacturing firm are separated into two broad categories. These include manufacturing costs and selling and administrative costs. This functional separation is important because each category of cost is treated differently in the accounting records. The different treatments are required to obtain proper matching.

There are three types of manufacturing costs. These include: 1) direct material or raw material, 2) direct labor, and 3) indirect manufacturing costs, or factory overhead. Direct material becomes the product, or becomes a part of the product. Direct labor converts the direct material into a finished product. Factory overhead represents all the other factory costs that cannot be directly identified with a particular product. This indirect category includes a variety of costs that are discussed in more detail in subsequent chapters. These three types of costs are also referred to as product costs, or inventoriable costs, because they are capitalized in (or charged to) the inventory, i.e., they become assets.

Accountants capitalize manufacturing costs to obtain proper matching. The matching concept is pervasive in accrual accounting and requires that costs and benefits are matched or brought together on the income statement. In a production setting, the idea is to match the costs of producing a product (or service) against the benefits, i.e., revenue derived from the sale. When the inventory is sold, these costs are charged to an expense account referred to as cost of goods sold. At the end of the accounting period, cost of goods sold is closed to the income summary where, theoretically, matching takes place. Remember that unexpired costs represent assets. Expired costs represent expenses. When the inventory is sold, we say these costs have expired, i.e., the benefits to be obtained (from the effort that generated the costs) have been recognized. Thus, manufacturing costs become expenses when they reach cost of goods sold, but represent assets until the sale takes place.

Selling and Administrative Costs

In traditional accounting systems16, selling and administrative costs are expensed in the period in which they are incurred. Theoretically, if there are future benefits associated with a cost, the cost should be capitalized as an asset rather than expensed. Certainly there are some future benefits associated with costs such as research and development, training, market promotion and advertising. However, these costs are expensed as incurred because it is difficult if not impossible to relate them to the future benefits. As a result, these costs are referred to as period costs.

In addition to separating costs into categories such as direct and indirect and manufacturing and non-manufacturing, costs are also frequently identified by their behavior in relation to changes in an activity level. This separation is helpful for planning and budgeting purposes. The major types of costs, in terms of cost behavior, are: 1) variable costs, and 2) fixed costs, 3) semi-variable costs and 4) semi-fixed costs. These concepts are illustrated graphically in Exhibit 1-3 and discussed individually below.

Variable Costs

Variable costs are those costs that vary with changes in the level of activity. Variable costs tend to increase at various rates that generate linear (straight line) or a variety of non-linear cost functions when the costs are plotted on a graph. Some examples are illustrated in the top left panel of Exhibit 1-3.17 The major activity that affects manufacturing costs is production volume, i.e., producing output. Production volume is frequently measured in terms of units produced, direct labor hours used, machine hours used, materials costs or some other production volume related measure. However, other activities that are not related to production volume might also be important in analyzing cost behavior. The recognition that non-production volume related activities also cause, or drive costs is a fundamental idea associated with activity based costing (ABC). ABC is introduced in the next chapter in connection with the various components of a cost accounting system and discussed in more detail in Chapter 7.

Fixed Costs

Fixed costs are defined as those costs that do not vary with changes in the activity level. Some horizontal cost functions are presented in the top right panel of Exhibit 1-3 to illustrate the idea. However, this does not mean that fixed costs remain constant. If a production volume based measure is used as the activity, a cost that changes for some reason other than a change in production activity is considered fixed. This simply means that the cost is driven by a non-production volume related phenomenon. For example, property taxes are considered fixed in traditional cost accounting systems that are typically based on production volume related activities. However, property taxes change when the taxing authority changes the tax rate or reassesses the property. The idea to grasp is that the designation of a particular cost as fixed or variable can change when it is analyzed in relation to a different activity. It is also important to understand that the notion of fixed and variable costs is a short run concept. All costs tend to be variable in the long run.

Semi-Variable and Semi-Fixed Costs

Semi-variable costs are part fixed and part variable. There is a minimum cost (the fixed portion) and a variable portion that increases as activity increases. Some examples of these mixed costs appear in the lower left panel of Exhibit 1-3.The point where the cost function intersects the vertical axis represents the fixed portion of the cost. There are also semi-fixed costs that do not change continuously as the level of activity changes, but do increase in steps as activity increases beyond various levels. These costs are sometimes referred to as step cost and step functions. For example, a single production supervisor (who's salary normally represents a fixed cost) might be adequate until production reaches a certain level, then a second supervisor would need to be hired. Supervisory costs might be driven by the number of production shifts. Step functions can take on many forms as illustrated in the lower right panel of Exhibit 1-3.

Cost Behavior Techniques

There are a variety of techniques for analyzing cost behavior. Some of the methods for estimating linear cost functions are discussed and illustrated in Chapter 3. More descriptive discussions of the various types of cost behavior are provided in Chapter 11.

FRAMEWORK: TWO GLOBAL VARIANTS OF CAPITALISM

Before we proceed any further into the domain of management accounting, it is important to consider the global environment in which firms now compete. In two fairly recent books, George Lodge and Lester Thurow provide a structure for understanding the global economy.18 According to these authors, there are two very different variants of capitalism. One familiar variant is the system traditionally practiced in the United States. This is referred to as individualistic capitalism. The other variant is the system practiced in Japan and in the unified European community. This system is referred to as communitarian capitalism. These two variants of capitalism are important because most of the assumptions and practices underlying the individualistic system are incompatible with the assumptions and practices underlying the communitarian system. The particular variant of capitalism embraced by society, determines to a large extent how individuals interact with each other, how businesses interact with other businesses and government, how companies are managed and more specifically for the purposes of this text, how internal accounting systems are designed and used to measure and evaluate performance. As a result, the dichotomy of capitalism provides a broad framework for the study of management and management accounting. This framework is discussed below and referred to frequently in subsequent chapters.

UNDERLYING CONCEPTS, CHARACTERISTICS AND ASSUMPTIONS

According to George Lodge, most countries display a mix of individualism and communitarianism. However, the United States has tended to be the most individualistic and Japan has tended to be the most communitarian. Other nations are somewhere between the two extremes.19 A brief sketch of the key economic concepts, characteristics and assumptions underlying the two conflicting competitive models is provided in Exhibit 1-4. These include: 1) how to optimize the performance of a system, 2) the key driving force in the economy, 3) the motivation for work, 4) the responsibility for training prior to employment, 5) the relationship between government and business, and 6) the purpose of government policy.

How to Optimize the Performance of a System

Perhaps the most important philosophical difference between the two variants of capitalism is the assumption concerning how to optimize the performance of a system. In the communitarian model, a system can be optimized only when cooperation exists at all levels within the system. There must be cooperation between individuals, departments and functional areas within a company, union and company, companies, industry groups and business and government. The source of this philosophy is not entirely clear, but it was promoted by W. Edwards Deming for at least forty years before his death in 1993 and practiced in Japan since 1950.20 The assumption underlying the individualistic model is that competition at all levels will lead to optimizing the performance of a system. The source of this philosophy is easily traced to the classical school of economics founded by Adam Smith. Smith wrote that an "invisible hand" leads individuals to unintentionally promote the good of society while seeking their own self interest.21 Although the classical economists were concerned mainly with the macroeconomic system, their views spilled over into microeconomic theory and business practices. For example, the neoclassical micro economists, who followed Smith, supported individualism and a "laissez faire", or free enterprise market. To both classical and neoclassical economists, a free market was self regulating and produced the maximum social benefits. Similar ideas can be found at the practice level in the works of Frederick W. Taylor and the scientific management movement where individual specialization and performance were emphasized to the extreme.

To summarize the key concepts, success in a communitarian system is believed to come from the collective efforts, or teamwork of all members of the system, while success in an individualistic system is believed to come from the efforts of individuals seeking their own self interest. In an individualistic system, optimizing the parts is assumed to optimize the whole. However, the assumption in a communitarian system is that optimizing the parts will automatically produce sub-optimization of the whole because of the interdependences among individuals and groups within the system.22

The Key Driving Force in the Economy

The driving force in the economy, according to the communitarian viewpoint, is the desire for long term growth and improvement of the system. On the other hand, the driving force in an individualistic system is the individual's desire for consumption and leisure in the present. These driving forces influence the goals and behavior of organizations and governmental units as well as individuals within the system. For example, during the five year period from 1985 to 1989, Japanese investment, as a percentage of its gross national product (GNP) was over twice that of the United States, i.e., 35.6% compared with 17%.23

The Motivation for Work or Work Ethic

The communitarian model includes the assumption that work itself provides intrinsic motivation and that being part of a winning team provides considerable rewards and satisfaction. People mainly live to contribute, to accomplish, to create and to gain respect from others for their efforts. Consumption and leisure are less important considerations for the individual.24 However, the individualistic system is based on the assumption that people are motivated to work mainly to increase consumption and leisure and to avoid unemployment. This hedonistic attitude can also be traced back to the neoclassical economists (or marginalist) who assumed that workers would attempt to maximize pleasure and minimize pain. This idea translates into maximizing the utility obtained from consumption and minimizing the disutility associated with work. Although the lack of work ethic associated with American workers has been challenged by behavioral scientist for a number of years, the structure of most American organizations (discussed below) has reflected this "lazy man" view until recently.25

The Responsibility for Training Prior to Employment

In a communitarian system, skills and training prior to employment are primarily viewed as the responsibility of society. For example, strong high schools with very low drop out rates of six or seven percent are typical in Japan and West Germany.26

Government and business supported apprenticeship programs are used to insure that the less capable high school students (academically) become functional members of society. In contrast, public schools are relatively weak in an individualistic system. For example, in the U.S., the high-school drop out rate is around twenty-nine percent and apprenticeship programs are much less common27. Although colleges are relatively strong in the American individualistic system, many non-college bound students (the "neglected majority") do not receive a marketable education.28 Although a discussion of the reasons for these differences is not within the scope of this textbook, the skill levels of individuals entering the workforce is an important determinant of competitiveness for the organizations who rely upon their skills. It is also important for any organization contemplating a change from an individualistic to a team oriented system.

Relationship between Government and Business

In the communitarian system, government works to support business and to promote cooperation between businesses and industry groups within the system. Government is responsible for a strong infrastructure including education, communication and transportation systems. Government in an individualistic system also recognizes the need for a strong infrastructure, but the classical view of government is still present in individualistic systems. To the classical economists, the best government was the government that governed least.29

Purpose of Government Policy

In a communitarian system such as Japan, government policy is designed to increase investment and savings (through tight credit controls) to generate long term growth in supply. However, in an individualistic system such as the United States, government policy is designed to promote as much competition as possible. Cooperation is viewed as detrimental to the economy because it leads to monopoly power. Thus, cooperation between companies and industry groups is to a large extent illegal in the American individualistic system. U.S. government policy is also used to promote growth in demand through easy credit, as opposed to promoting substantive growth and improvement in the infrastructure.30

MAJOR BUSINESS CONCEPTS, ATTITUDES AND PRACTICES

Exhibit 1-5 provides a summary comparison of twelve major business concepts, attitudes and practices underlying the two competitive models. These include: 1) the organization’s dominant objective and focus, 2) organizational structure, 3) how profits are used, 4) the hierarchy of the organization’s constituencies, 5) employment and job security, 6) responsibility for training after employment, 7) the route to management, 8) management’s attitude towards teamwork, 9) management’s behavior in an economic recession, 10) management’s view of leadership, 11) management’s attitude towards problems and 12) the tools of management.

Dominant Objective and Focus

The primary business objective in a communitarian system is the long term growth and improvement of the organization. Thurow refers to this idea as "strategic conquest". Profitability is secondary and viewed mainly as a requirement for future growth. Individualistic organizations, on the other hand, tend to emphasize short run profitability as the dominant objective.

In a survey of U.S. and Japanese companies, (227 U.S. and 291 Japanese) U.S. executives ranked a measure of profitability first, stock price second and market share third, while the Japanese executives ranked market share first, profitability second and new products third.31 Although this survey was conducted during 1980, American executives still appeared to be emphasizing short term objectives ten years later. In a 1990 world competitiveness report, U.S. firms were ranked next to last out of twenty-three industrial countries in terms of future orientation. The Japanese were ranked number one.32

Communitarian organizations tend to emphasize a concept referred to as employee empowerment where self regulated teams make consensus decisions at the work level. These so-called bottom-up organizations tend to be horizontal, flat or lean in that there are relatively few layers of management. In contrast, individualistic organizations tend to be structured vertically in a top down manner with a hierarchy of management layers. Specialized jobs involving a few simple repetitive tasks are designed at the work level using the concepts of scientific management. Even so, the individualistic system includes a relatively large number of supervisory positions to compensate for the "lazy man" work ethic mentioned above. For example, a study comparing the cost of producing Ford Escorts in different countries indicated that forty percent of the Japanese cost advantage resulted from lower white-collar costs in the Japanese organizations.33

How Profits Are Used

In an organization structured around the communitarian philosophy, profits are used mainly to build for the future. This follows naturally from the "strategic conquest" objective mentioned above. However, the individualistic enterprise mainly uses profits to enhance the consumption of stockholders. These ideas are supported by a comparison of dividend payout ratios. In 1990, dividends accounted for only thirty percent of after tax profits for Japanese companies while U.S. companies distributed eighty-two percent.34

Hierarchy of Organization’s Constituencies

From the communitarian viewpoint, employees are the most important key to global competitiveness, customers are second, shareholders are third and suppliers are fourth. The idea is that if the company’s employees are not satisfied, this dissatisfaction will affect the quality of their work and their relationships with customers. Employees, customers, and suppliers work together as a family to achieve a common goal. All constituencies along the value chain are important as well as the company’s stockholders. In individualistic organizations, on the other hand, the organization’s top three constituencies are reversed. Stockholders are viewed as the most important group, customers are second and employees are a distant third. Employees are treated more as a factor of production like buildings and equipment to be acquired and disposed of as needed. Suppliers likewise are expendable and must compete with each other for the company’s business. The four constituencies are definitely not part of the same family.35

Employment and Job Security

The position of employees in the hierarchy discussed above is clearly reflected by an organization’s employment policies. Communitarian firms tend to provide lifetime employment, promote from within the organization and emphasize job enrichment. Companies in an individualistic system do not provide a comparable level of job security. Labor turnover rates in the U.S. and Japan provide considerable support for this statement. The Japanese labor turnover rate is around 3.5% per year. In contrast, the U.S. labor turnover rate is around 4% per month.36 The Japanese, according to one observer, view the employee-employer relationship as a marriage, while Americans tend to view the relationship as a casual date.37

Responsibility For Training After Employment

In communitarian companies, cross training and job rotation are essential to support self regulating teams and to promote bonding with the organization. It is reasonable to assume that relatively large training expenditures will pay off due to the very low labor turnover rates in these environments. Individualistic companies logically spend less on training because of high labor turnover coupled with the influence of scientific management. If jobs are limited to a few simple repetitive tasks, employees can be laid-off, or fired and easily replaced when needed. These ideas are supported by the world competitiveness report mentioned earlier. In the category of quantity and quality of on-the-job training, Japanese companies were ranked number 1, German companies number 2 and U.S. companies number 11 out of twenty-three industrial countries.38

Route To Management

The route or career path to a management position is also very different in the two economic variants of capitalism. In a communitarian company, broadly educated college graduates develop a cumulative multi-function knowledge of the organization before they become managers. In other words, they become company generalist through a long internship program, rather than functional specialist. Since communitarian managers develop company specific knowledge, they are not particularly mobile or marketable outside the organization. However, this company specific orientation and the policy of promoting from within the organization increases the manager’s internal mobility. The combination of internal mobility and life time employment establishes a bond between the manager and the organization. From the company perspective, the resulting low labor turnover rates support the relatively heavy expenditures on management training.

The individualistic system is quite different. College graduates who have specialized in a particular area of study such as industrial engineering, accounting or marketing are hired by organizations to work in that particular functional area. After acquiring experience in their particular specialty, they become managers. Their orientation to a specific business function enhances their mobility in the external labor market, but they are frequently locked into their chosen specialty area. Of course some managers do break out of their narrow specialty areas to move up the management hierarchy. External mobility is clearly an advantage to the individual in an environment where employees are treated as factors of production or commodities. Disloyalty to the company is not an insoluble problem for the organization in an individualistic system however, because a functional specialist can be fairly easily replaced with another functional specialist. Company specific knowledge is less important in a system organized around specialists rather than generalists.

Management’s Attitude Towards Teamwork

In communitarian organizations, teamwork and cooperation are viewed as the only way to optimize the performance of the system. Competition among individuals, departments or segments within an organization and management control techniques that emphasize individualistic performance, are viewed as detrimental to the system. If the performances of the subsystems are optimized, the system will not be optimized. On the other hand, individualistic organizations tend to view teamwork, or any organized group of workers with suspicion. For example, American companies have had a long adversarial relationship with labor unions. American national unions tend to require a large number of job classifications, prohibit cross-training and use the strike as a weapon to obtain higher wages and benefits for union members. In comparison, Japanese unions are company sponsored and promote teamwork by supporting a small number of job classifications, considerable cross-training and a no-strike policy.39

Management’s Behavior In Economic Downturn

During a recession or economic downturn, a communitarian organization tends to reduce dividends first, then management compensation. Employees’ wages and jobs are reduced only as a last resort. Workers are viewed as part of the family, so they are retrained and relocated within the company. In an individualistic organization, workers tend to be viewed as replaceable parts. Therefore, in recessionary periods, worker’s pay and jobs are cut first, then management compensation. Dividends are reduced only as a last resort.

Management’s View Of Leadership

The communitarian view of leadership is probably articulated best in the works of W. Edwards Deming. To Deming, leadership requires knowledge of processes and an understanding of the variability within the system. From Deming’s perspective, leaders know that most of the problems within a system are created by the variability within the system itself, not by the people working in the system. However, individualistic managers tend to view leadership from a top down control perspective. The leader specifies the desired results and then rewards or punishes workers on the basis of these specifications. The communitarian leader views workers as colleagues in an adult-adult relationship, while the individualistic leader views the relationship more in terms an adult-child orientation. In a communitarian company, employees work with management. In an individualistic company, employees work for (and sometimes against) management. Notice that a manager’s view of leadership follows logically from the company’s overall structure and policies towards employees. (See Deming's New Economics summary and the Hayes & Abernathy summary for more on the problems associated with the individualistic form of leadership).

Management’s Attitude Toward Problems

A communitarian leader tends to blame the system first, not the people working in the system. The communitarian approach emphasizes continuously seeking to improve the system. In an individualistic environment, according to Deming, managers blame people for problems because they do not understand the system. Another way to state this idea is to say that the communitarian management style is process oriented, while the individualistic management style is results oriented. Communitarian managers tend to manage the processes and work that people do, while individualistic managers tend to manage by results, frequently financial results.40

Tools Of Management

Managers in a communitarian company manage by promoting a bottom up approach referred to as employee empowerment. Self directed teams monitor their own performance with techniques such as statistical control charts. The manager facilitates, counsels and teaches to promote continuous improvement, job enhancement and teamwork. The system depends on trust, not fear. According to Deming, a leader does not judge or rank employees.41 The traditional individualistic approaches include management by objectives, merit ratings, incentive pay, quotas, standards and piecework systems. Deming argues that these tools, common in the individualistic organization, are fear oriented and destroy cooperation and teamwork. Of course, cooperation and teamwork provides the foundation of a communitarian organization.

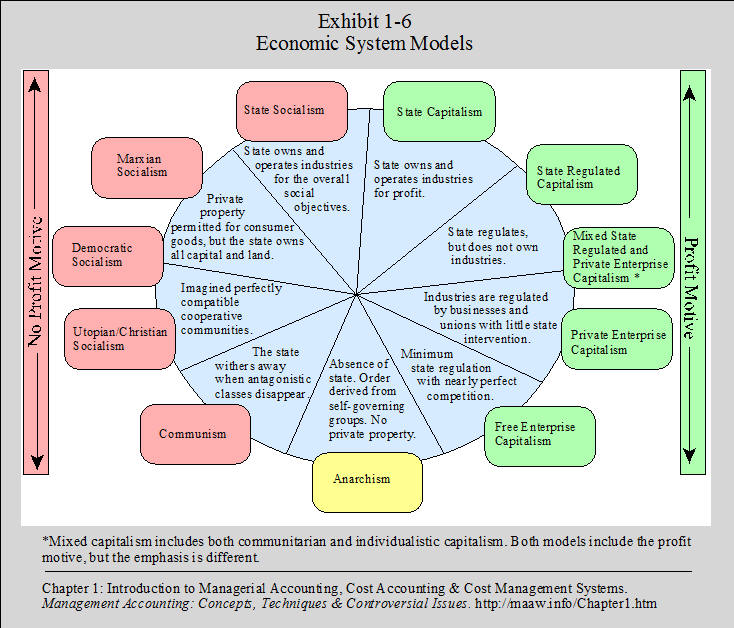

PLACEMENT WITHIN THE LARGER ECONOMIC SYSTEM

Although the individualistic and communitarian capitalist models may appear to be radically different, they are very similar when placed within the whole array of possible economic systems. Consider the variety of alternatives that appear in the economic system models illustration presented in Exhibit 1-6. The models at the top of the illustration represent maximum government ownership of capital and land, while the models at the bottom represent the absence of government. The models on the left-hand side exclude the profit motive, while the models on the right-hand side include the profit motive.42 On the lower right-hand side, free enterprise capitalism represents the maximum individual freedom within a capitalist system, while state capitalism represents the minimum individual freedom. On the left-hand side, communism represents the maximum individual freedom for a socialist system, while state socialism represents the least individual freedom. Notice that both communitarian capitalism and individualistic capitalism fall into the same category. Both systems include a mixture of state (i.e., government) regulation and private enterprise. In terms of the whole scheme of possible economic systems, the two models are very close together. These two models mainly differ in terms of the amount of emphasis placed on individual freedom. It is important to understand that while individual freedom represents the greatest strength of capitalism, it also represents the greatest potential weakness. Finding the optimum mix of individual freedom and cooperation within a larger community is the goal of both systems.

Mixed Versus Pure Organizations

Today there are few, if any pure systems. Although some have argued that by the year 2000 all workers would be part of a team43, it is likely that there will always be a mixture of cooperation and competition within any system. Until recently most American companies have emphasized individual skills and performance. However, since 1980 many American organizations have redesigned their systems to emphasize cooperation and teamwork and to de-emphasize competition between individuals and segments within an organization.44 Currently the World Economic Forum ranks countries on the basis of 12 pillars of competitiveness. The 11th pillar is business sophistication defined as follows: "Business sophistication concerns two elements that are intricately linked: the quality of a country’s overall business networks and the quality of individual firms’ operations and strategies."45

Relevance Of Framework To Accounting

Many of the ideas and concepts associated with communitarian capitalism are linked to attempts to develop new and better approaches to accounting and management such as activity management, activity costing, activity based product costing (ABC), just-in-time (JIT), investment management, the expanded use of statistical control charts and total quality management (TQM).46 As we proceed through this textbook we will return to these ideas frequently to emphasize that accounting is not a generic set of rules that fits all firms under all circumstances. To be useful to management, internal accounting systems must be designed, and redesigned when necessary, to fit the organization’s structure, strategy and competitive orientation. Accounting systems that were designed to support an organization competing under the assumptions of individualistic capitalism are not likely to be as useful to organizations that are restructuring around the communitarian concepts. Many companies are evolving in this way, from a system based on individualistic values to a system based on cooperation and teamwork47. Accounting scholars agree that accounting systems must continue to evolve to complement these changes. However, questions concerning what to change and how to change it have created a considerable number of controversial issues. We will consider many of these issues in subsequent chapters. (See a graphic view of the Evolution of Management Accounting).

APPENDIX 1-1: THE CERTIFIED MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTANT

Obtaining the CMA designation can enhance your marketability48. It should be of special interest to those who do well in accounting courses, but who do not want to become public accountants. Consider the following.

In 1972, the National Association of Accountants (NAA) established the Institute of Management Accounting to administer the CMA program. The original IMA became the Institute of Certified Management Accountants and NAA changed its name to the Institute of Management Accountants. The CMA program was developed to provide recognition and credibility to Management Accounting as a professional discipline.

The New CMA Exam Structure for 2010

In May 2010 the CMA exam changed to a two part format emphasizing the critical skills related to financial planning, analysis, control, and decision support. There are two four-hour exams each consisting of 100 multiple choice questions and two 30-minute essay questions.

Part 1: Financial Planning, Performance and Control

Planning, budgeting, and forecasting

Performance management

Cost management

Internal controls

Part 2: Financial Decision Making

Financial statement analysis

Corporate finance

Decision analysis and risk management

Investment decisions

Professional ethics

All topics in both sections will be tested up to level "C", i.e., a candidate's ability to synthesize information, evaluate a situation, and make recommendations. Levels "A" (knowledge and comprehension), and "B" (application and analysis) are also tested. The increased emphasis on "C" level knowledge is a change from the previous four part exam.49

The New CMA Exam Structure for 2020

The new 2020 structure places more emphasis on technology, ethics, strategy, and decision analysis.

Part I: Financial Planning, Performance, and Analytics

Cost Management

Internal Controls

Technology and Analytics

External Financial Reporting Decisions

Planning, Budgeting, and Forecasting

Performance Management

Part 2: Strategic Financial Management

Risk Management

Investment Management

Professional Ethics

Financial Statement Analysis

Corporate Finance

Decision Analysis

The following link provides more specific information about the current CMA exam. Imanet cma-certification?

There are many different certifications for accountants that support a variety of specialty areas. For a list and links see Accounting Certifications.

1See H. T. Johnson and R. S. Kaplan, 1987, Relevance Lost: The Rise and Fall of Management Accounting (Harvard Business School Press): Chapter 2. (MAAW's Relevance Lost section); Johnson, H. T. 1983. The search for gain in markets and firms: A review of the historical emergence of management accounting systems. Accounting, Organizations and Society 8(2-3): 139-146. (Summary); Garner, S. P. 1947. Historical development of cost accounting. The Accounting Review (October): 385-389.); and Garner, S. P. 1954. Evolution of Cost Accounting to 1925. Tuscaloosa, AL. University of Alabama Press.

2 For a thought provoking discussion of operational definitions, see W. Edwards Deming, 1986, Out of the Crisis, (Massachusetts Institute of Technology Center for Advanced Engineering Study): Chapter 9. (See MAAW's section on Deming).

3 See Bedford, N. 1971. The Income Concept Complex: Expansion or Decline.Asset Valuation, ed. Robert Sterling. Lawrence, Kansas: Scholars Book Company: 142.1. Why is the distinction between concept definitions and operational definitions important? (See section on definitions).

2. In Exhibit 1-1, financial accounting is defined as part of management accounting. Discuss the logic underlying this concept definition.

3. Conceptually, how do public accounting, governmental accounting and management accounting differ? (See Exhibit 1-1 and subsequent discussion).

4. Explain how cost accounting is linked to tax accounting, financial accounting and managerial accounting. (See Exhibit 1-2 and subsequent discussion).

5. Explain how and why the emphasis of cost accounting education changed around 1950? (See cost accounting changing emphasis).

6. Explain how cost accounting education began to change again in 1987. (See cost accounting changing emphasis).

7. How does cost accounting differ from cost management?

8. What is the conceptual difference between cost management and activity management?

9. How is investment management more comprehensive than capital budgeting?

10. In your opinion, should performance measurement systems be designed to influence behavior, or should they be neutral? Explain your reasoning. (See Dual Purpose of accounting measurements).

11. Discuss how performance measurements affect performance? (See Dual Purpose of accounting measurements).

12. Explain the concept of variation or variability.

13. Consider the concept of variability in connection with your performance in the following areas: academic, athletic and employment if applicable. How much control do you think you have over your performance ranking, stated as a percentage? Why?

14. Based on your experience, what percentage of the variation in grades in school is caused by the system (broadly defined as economic, social and educational) as opposed to the individual efforts of students? Do you think faculty and administrators would agree with your percentages? Why?

15. What does control mean statistically? (See concept of control).

16. Distinguish between common causes and special causes of variation. How are these concepts used to develop a control chart? (See concept of control and subsequent discussion).

17. Conceptually, what is the difference between direct and indirect costs? (See the management accounting terminology section and the Gordon & Loeb summary).

18. In traditional cost accounting systems, what is the difference between product cost and inventoriable cost?

19. What is the matching concept? (See Matching Concept).

20. How do the terms expired and unexpired relate to the matching concept? (See Matching Concept).

21. What is the difference between an asset and an expense? (See Matching Concept).

22. Why is cost behavior analysis a short run concept? (See cost behavior).

23. Provide concept definitions for: variable costs, fixed costs, semi-variable costs and semi-fixed costs. (See cost behavior).

(Go to a similar set of Framework Questions with links related to the answers for questions 24-50).

24. What is a system?

25. Describe the main assumptions underlying the two variants of capitalism.

26. When is teamwork or cooperation needed to optimize a system, i.e., what system characteristics cause a need for teamwork?

27. Where did the emphasis on competition originate?

28. What is the most cooperative form of life?

a. Humans, b. Wolves c. Army ants d. Killer bees e. Some other species

29. Compare McGregor’s concepts of Theory X and Theory Y to the two variants of capitalism.

30. What is the driving force underlying the two types of economic systems?

31. What does the term infrastructure mean?

32. Why is infrastructure important?

33. Who should pay for education?

34. Should the federal government promote supply or demand?

35. Which type of capitalist system is oriented more towards short term profits? Why?

36. What is a flat organization?

37. Which system promotes a flat organizational structure?

38. What is needed to support a flat organization?

39. Are the concepts of individualistic organization and flat organization compatible?

40. What advantage does a flat organization have over a vertical organization?

41. Who should be first in the hierarchy of an organization’s constituencies, employees, customers, or stockholders?

42. Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of the individualistic system of capitalism, first from the employee’s point of view and then from the employer’s point of view. Some areas for consideration include employee acquisition, internal and external mobility, training costs and cost of supervision. (See the table in the Framework questions).

43. Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of the communitarian system of capitalism from the employee’s view point and then from the employer’s view point in the same areas mentioned above. (See the table in the Framework questions).

44. How does the concept of leadership differ in the two systems?

45. Which type of leader blames the system for problems first? Why?

46. Which type of leader would rank employees? Why?

47. Do you think Americans tend to be reluctant to accept the idea of teamwork? Do you think this tendency is controlled more by the system, or the individual?

48. Which type of leader believes that employees are mainly motivated by money?

49. What is the key difference between socialism and capitalism? (See the Economic system graphic)

50. Why are the global variants of capitalism relevant to the study of cost and managerial accounting? (See Relevance of Framework to Accounting, the Quality or Else summary and Handy summary).

Problem 1-1

Circle the letter of your choice for each of the multiple choice questions below.

1. Which of the following represents part of Management Accounting?

a. Financial Accounting.

b. Tax Accounting.

c. Cost Accounting.

d. Managerial Accounting.

e. All of the above.

2. The broad conceptual definition of management accounting presented in the

text excludes

a. public accounting.

b. financial accounting.

c. governmental accounting.

d. a and c.

e. all of the above.

3. Conceptually, the difference between cost management and activity

management is that

a. cost management is proactive and activity management is reactive.

b. cost management places emphasis on costs while activity management places emphasis on the work that causes the costs.

c. cost management is designed for external users while activity management

is designed for internal use.

d. a and b.

e. all of these.

4. Managers in which type of economic system tend to place greater emphasis

on long term growth?

a. Communitarian capitalism.

b. Individualistic capitalism.

c. Both systems.

d. Neither system.

5. In cost accounting, costs are classified as variable costs if they

a. change during the accounting period.

b. change as the activity level changes.

c. are indirect costs.

d. are not related to the activity measurement.

e. none of these.

6. In cost accounting, fixed costs are those costs that

a. are constant.

b. are closely related to the activity measurement.

c. are not affected by the level of activity during the accounting period.

d. include all the indirect costs.

e. c and d

7. Conceptually, the main difference between financial accounting and

managerial accounting is that

a. public accountants are engaged in financial accounting and private

accountants are

engaged in managerial accounting.

b. financial accounting information is mainly designed for external users

while managerial

accounting information is designed for internal users.

c. cost accounting is required for managerial accounting, but not for

financial

accounting.

d. GAAP can be used for financial accounting, but not for managerial

accounting.

e. none of these.

8. In accounting, the matching concept refers to

a. assigning costs to the type of production process in which the company is

engaged.

b. assigning costs to the products that cause the costs.

c. assigning costs to expense in the time periods when the benefits

associated with the

costs are recognized.

d. separating variable costs and fixed costs so that variable costs can be

matched with

products and fixed cost can be matched with time periods.

e. none of these.

9. Theoretically, short term profit maximization is the main objective in

a. Communitarian capitalism.

b. Individualistic capitalism.

c. Both systems (a and b.)

d. neither system.

10. An underlying assumption of the system is that work mainly provides

disutility, thus workers will tend to avoid work if possible.

a. Communitarian capitalism.

b. Individualistic capitalism.

c. Both systems (a and b).

d. neither system.

11. The hierarchy of an organization's constituencies is: employees first,

customers second, and stockholders third. This is consistent with

a. Communitarian capitalism.

b. Individualistic capitalism.

c. Both systems (a and b).

d. neither system.

12. Promoting competition between individuals is viewed as a way to improve

efficiency in

a. Communitarian capitalism.

b. Individualistic capitalism.

c. Both systems (a and b).

d. neither system.

13. Managers tend to blame the system for most of the variation in

performance in

a. Communitarian capitalism.

b. Individualistic capitalism.

c. Both systems (a and b).

d. neither system.

14. The desire for consumption and leisure is viewed as the main driving

force in the economy in

a. Communitarian capitalism.

b. Individualistic capitalism.

c. Both systems (a and b).

d. neither system.

15. Where managers tend to manage processes by facilitating and counseling

workers, rather than ranking workers based on numerical results.

a. Communitarian capitalism.

b. Individualistic capitalism.

c. Both systems (a and b).

d. neither system.

16. Which of these statements is true?

a. The matching concept requires that we distinguish between expired and

unexpired costs.

b. To say that a cost has expired means that the benefits associated with the

expenditure have been recognized.

c. Most costs that represent future benefits are classified as assets.

d. Matching is required for external reporting.

e. All of the above.