Summary by James R. Martin, Ph.D., CMA

Professor Emeritus, University of South Florida

Management Theory Main |

Organization Structure Main |

Process Design Main

Many U.S. companies are unprepared to compete against Japanese companies and entrepreneurial ventures that are proving every day that drastically better levels of performance are possible. Although some of these companies have made heavy investments in information technology, they have used technology to automate the old existing processes. But this does not address the fundamental deficiencies of their old job designs, work flows, control mechanisms, and organization structures. The old processes should not be automated. Instead, they should be obliterated and radically redesigned, or reengineered to achieve dramatic improvements in performance. This requires breaking the old rules and developing new imaginative ways to perform work. The good news is that some companies have successfully reengineered their processes. The purpose of this paper is to describe some of these efforts and to provide some rules of thumb for other companies who embark on the reengineering path to change.

Ford and Mutual Benefit Life Insurance

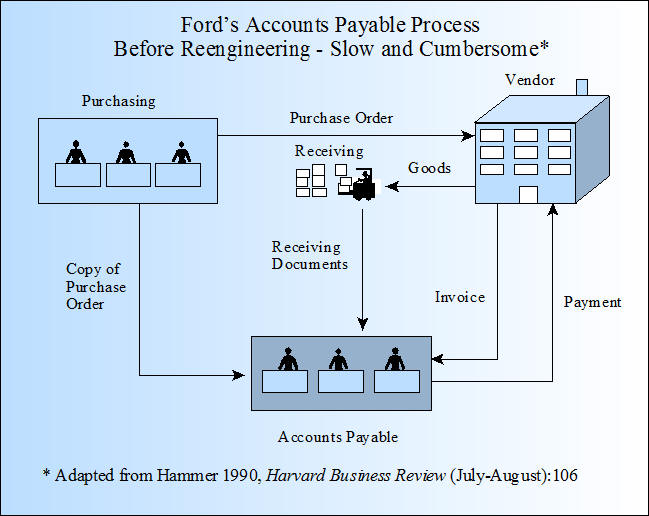

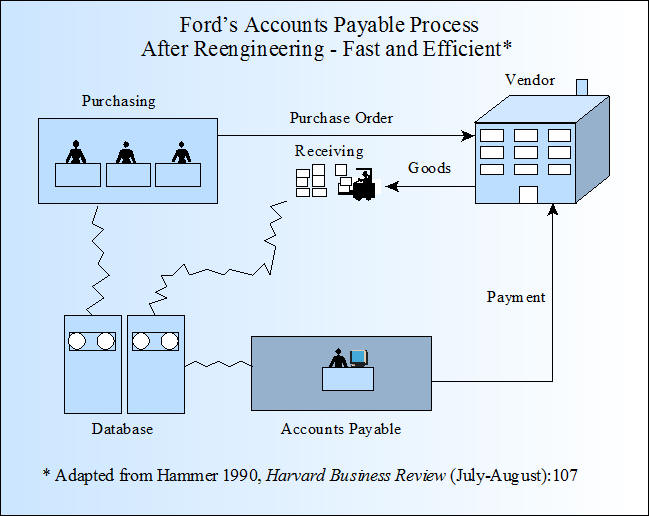

Ford Motor Company reengineered its accounts payable process. The old process required the accounting department to match 14 data items between receipt record, purchase order, and invoice before it could pay a vendor. The new process requires matching only 3 items - part number, unit of measure, and supplier code between purchase order and receipt record - performed automatically before the computer prepares a check. This redesign reduced head count by 75% , simplified materials control and produced more accurate financial information.

Mutual Benefit Life Insurance reengineered its insurance application process from a 30 step, 5 department, 19 people process to one where a case manager (using a PC-based workstation and expert system) performs all of the tasks associated with an insurance application. The company eliminated 100 field office positions, reduced processing time from 5-25 days to 2-5 days, while doubling their capacity to process applications.

The Essence of Reengineering

The old rules of work design are based on assumptions about technology, people, and organizations that are no longer valid. Work has been organized as a sequence of separate tasks that require complex mechanisms to track and measure based on the industrial revolution concepts of labor specialization and economies of scale. This has resulted in fragmented processes that lack the integration required to maintain quality and service. Instead they promote tunnel vision oriented towards narrow goals of individual functions or departments, rather than the goals of the process as a whole. Reengineering involves looking at business processes from a cross-functional perspective and breaking away from conventional wisdom and constraints to achieve dramatic levels of improvement.

Principles of Reengineering

1. Organize around outcomes, not tasks.

The idea is to design a person's job around an outcome or completed process, e.g., Mutual Benefit Life's use of one person (a case manager) to perform all the tasks required for a completed insurance application. Another example is where a company redesigned its equipment sales and installation process from one that involved a number of departments and steps to one where a single customer service representative oversees the whole process of selling, delivering, and installing equipment.

2. Have those who use the output of the process perform the process.

An example of this principle is where each department makes their own purchases with the aid of an expert system and a database of approved vendors, rather than using a specialized purchasing department. Another example is where spare parts of an electronic equipment manufacturer are stored at their customer's sites through a computerized inventory system. When a customer has an equipment problem, these spare parts and a diagnostic support system allows the customer to make their own simple repairs.

3. Subsume information-processing work into the real work that produces the information.

An example of this principle is Ford's redesigned accounts payable process where receiving processes the information about goods received rather than sending it to accounts payable.

4. Treat geographically dispersed resources as though they were centralized.

For example, Hewlett-Packard designed a system where a corporate purchasing unit maintains a shared database on vendors, and coordinates the purchases of 50 manufacturing units allowing each unit to issue its on purchase orders. The corporate unit uses the database to negotiate contracts for the company and to monitor the units.

5. Link parallel activities instead of integrating their results.

Using communication networks, shared databases, and teleconferencing, independent groups involved in activities such as product development can be brought together to coordinate their work.

6. Put the decision point where the work is performed, and build control into the process.

The idea is to use information technology and expert systems to enable people to make their own decisions. The workers become self-managing and self-controlling which eliminates the old management hierarchy and bureaucracy to compress and flatten the organization. The manager's role changes to supporter and facilitator. Mutual Benefit Life's redesigned insurance application process provides an example of this principle.

7. Capture information once and at the source.

This is a simple idea where previously independent systems can be integrated by using an on-line relational database, bar coding, and electronic data interchange. Ford's redesigned accounts payable process provides an example.

Think Big

Reengineering triggers all sorts of changes in job designs, career paths, recruitment and training programs, promotion policies, management systems, and organization structures. These changes create a considerable strain on everyone in the organization, and the inevitable resistance to change requires executive leadership with a real vision and commitment. U.S. companies need fast and dramatic improvements to compete against streamlined Japanese companies and sleek startups. Vision and reengineering will provide the way.

_________________________________________________

Related articles, books and summaries:

Champy, J. 1995. Reengineering Management: The Mandate for New Leadership. Harper Business.

Champy, J. and H. Greenspun. 2010. Reengineering Health Care: A Manifesto for Radically Rethinking Health Care Delivery. FT Press.

Elliott, R. K. 1992. The third wave breaks on the shores of accounting. Accounting Horizons 6 (June): 61-85. (Summary).

Hammer, M. 2001. The Agenda: What Every Business Must Do to Dominate the Decade. Crown Pub.

Hammer, M. 2001. The superefficient company. Harvard Business Review (September): 82-91. (Summary).

Hammer, M. 2002. Process management and the future of six sigma. MIT Sloan Management Review (Winter): 26-32.

Hammer, M. 2004. Deep change: How operational innovation can transform your company. Harvard Business Review (April): 84-93.

Hammer, M. 2007. The process audit. Harvard Business Review (April): 111-123. (Note).

Hammer, M. and J. Champy. 1993. Reengineering the Corporation. Harper Business. ("The core message of our book... It is no longer necessary or desirable for companies to organize their work around Adam Smith's division of labor. Task-oriented jobs in today's world of customers, competition, and change are obsolete. Instead companies must organize work around process."... "Companies today consist of functional silos, or stovepipes, vertical structures built on narrow pieces of a process. ... The contemporary performance problems that companies experience are the inevitable consequences of process fragmentation." p. 28).

Parker, L. D. 1984. Control in organizational life: The contribution of Mary Parker Follett. The Academy of Management Review 9(4): 736-745. (Note).