Chapters 19-21

Study Guide by James R. Martin, Ph.D., CMA

Professor Emeritus, University of South Florida

Oser Summary Main Page

Chapter 19: Monetary Economics

Some of the schools of economics emphasized monetary phenomena more than others, but there is no distinct or separate school of monetary economics. Money was viewed by the classical, Marxist and the early marginalists schools as a veil to be overcome to examine the real world. Mitchell and Keynes combined monetary analysis with other fundamental economic processes. As the growth of banking, credit, business fluctuations, and monetary policy grew, money became more important in economic theory. This chapter includes the work of Wicksell, Fisher, and Hawtry who were all in the neoclassical or marginalist tradition. These authors developed an area that had been neglected, but growing in importance, helped integrate monetary analysis into general economic theory, and in the process may have exaggerated the role of money in the economic system.

Wicksell

John Gustav Knut Wicksell (1851-1926) was a scholar and a social reformer. His major contributions to economic theory were his analysis of interest rates in achieving an equilibrium in prices, or in generating inflation or deflation, his recognition of the potential for the government and central bank to promote price stability, and his savings-investment approach to monetary phenomena that was a precursor of Keynesian economics.

Wicksell analyzed interest rates to explain price fluctuations. The money rate of interest depends on the supply and demand for real capital. The supply of capital flows from people who save to accumulate wealth. The demand for capital depends on its potential profits or marginal productivity. The normal or natural rate of interest is where the demand for loan capital and the supply of savings exactly agree. The normal rate more or less corresponds to the expected yield on newly created capital, and is applicable to individuals. Banks are more complicated because they create credit. Where banks lend money at lower or higher rates than the normal rate, equilibrium is disturbed. Prices will rise without limit if the bank rate of interest is lower than the normal rate, and fall if the bank rate of interest is above the normal rate. When the normal and bank rates are equal, the banking and credit system will be neutral, and prices will be stable. In Interest and Prices published in 1898, Wicksell was perhaps the first to advocate stabilizing wholesale prices by controlling discount and interest rates.

Business cycle fluctuations are caused when technological and commercial progress does not keep up with the increase in needs. Attempts to convert large amounts of liquid capital into fixed capital creates a boom, but if no new technology provides a potential profit in excess of the margin of risk, depression occurs.

Banks have an obligation to society to provide the public with a medium of exchange in an adequate amount to stabilize prices. The free coinage of gold should be suspended. This would prevent the growing production of gold which would, if allowed to continue cause the expansion of currency, interest rates to fall, and prices to rise. Wicksell argued that the world should adopt an international paper standard.

Wicksell also analyzed the theory of forced savings. Bentham, Mill, and Walrus had written about the idea of "forced frugality" earlier. If a bank loan is made to finance a new enterprise with no corresponding accumulation of capital, more land and labor would be employed at producing capital goods, leaving less for consumer goods, although the demand for consumption would increase. With rising pricing, consumption would be restricted, and entrepreneurs would require fewer capital goods than originally expected. The forced restriction in consumption would represent the real accumulation of capital that is needed for capital investment to increase.

Wicksell accepted the idea from the marginalist and classical schools that equilibrium at full employment was the normal tendency of the economy. Depressions were viewed as monetary phenomena and secondary imbalances in a dynamic economy. His historical significance is that he combined general and monetary theory, and developed a theory of the cumulative process of expansion and contraction of business activity.

Fisher

Irving Fisher (1867-1947) was a mathematician who became an economist. He restated the quantity theory of money based on the equation of exchange. According to Fisher, the purchasing power of money or its reciprocal, the level of prices have five determinants: the volume of currency in circulation, its velocity of circulation, the volume of bank deposits subject to check, its velocity, and the volume of trade. His equation was as follows:

MV + M'V' = PT

M = the quantity of currency

V = the velocity of

circulation of M

M' = the quantity of demand deposits

V' = the

velocity of circulation of M'

P = the average level of prices

T = the

quantity of goods and services sold

Prices vary directly with the quantity of money (M and M') and their velocity of circulation (V and V'), and inversely with the volume of trade (T). The first part of these relationships represents the quantity theory of money. Fisher assumed that the volume of deposits (M') had a definite relation to the quantity of currency in circulation (M).

The cause and effect relationship between the quantity of money and the price level required the assumption that the velocity of circulation and the volume of trade were constant. Fisher recognized that the volume of trade grows in the long run, but in the short run, with a fully employed economy, the currency in circulation would normally determine the price level. If the quantity theory of money is valid, the price level and the economy could be stabilized by controlling the quantity of currency in circulation. His plan was to make paper money redeemable on demand in a quantity of gold that would represent constant purchasing power. Gold coinage would be abandoned, and gold certificates or paper money would be redeemable in gold bullion. To maintain stability, the government would adjust the quantity of gold bullion it would give or take for a paper dollar.

After the stock market crash of 1929, when Fisher and his wife lost eight to ten million dollars, he saw the growth of debts as the greatest cause of deflation and depression. Excess debts causes liquidation and the dumping of goods on the market. He believed that the fluctuations in demand deposits, based on bank loans was the greatest cause of business fluctuations. His solution was to require 100 percent reserves behind demand deposits, which would eliminate the process of creating and destroying money from the banking business. A government currency commission would buy liquid bank assets for currency, or lend banks currency using those assets as security up to 100 percent of a bank's checking deposits. Banks could lend out their own money or money put into savings accounts. This would eliminate bank failures, most government debt, most bank earnings, and most importantly, great inflations and deflations, alleviating booms and depressions. As a substitute for the gold price variations that Fisher had advocated earlier, the currency commission would buy securities when the index was below par and sell when above, a mechanism of open market operations now used by the Federal Reserve System.

Fisher believed that factors such as over-production, under-consumption, over-confidence, over-investment, over-capacity, over-investment, over-savings, and over-spending played a subordinate role as compared to over-indebtedness (the "debt disease") and deflation (the "dollar disease") in causing booms and depressions.

Fisher was a pioneer in developing the new field of economics and was honored by being elected president of the American Economic Association, the American Statistical Association, and the Econometric Society.

Hawtrey

Ralph George Hawtrey (1870-1975) was a British treasury official who wrote several books about monetary economics and business fluctuations which he attributed to the instability of credit. Hawtrey's key figure was the wholesale merchant, and his key factor was the interest rate. The effect of credit restrictions on producers was thought to be small, but the wholesaler was believed to be very sensitive to the rate of interest since his markup was small. Business fluctuations occurred because of the instability of credit working through the merchants to disturb the rest of the economy. The central bank could regulate credit and promote stability. Central bank open-market operations, changes in the rediscount rate, and varying the reserve requirements of commercial banks are the appropriate remedies for the instability of credit and economic activity. Raising interest rates and restricting bank reserves can reduce inflation, but lowering interest rates and greater bank reserves may not stimulate a revival. After the depression of the 1930's Hawtrey wrote that direct government expenditures might be the only way to keep consumer and investment spending from declining further. The effect of public works is obtained more slowly, but deficit spending may produce some positive results.

Chapter 20: The Departure From Pure Competition

Theories concerned with monopoly and with monopolistic or imperfect competition arose because the theory of pure competition became increasing indefensible. Pure competition had some relevance in relation to agriculture, but even there with only a few buyers in markets such as tobacco, meat, grain, and milk, along with government intervention in agriculture, the theory becomes irrelevant to the real world. In terms of industrial production, pure competition has even less relevance since the theory assumes many buyers and sellers who deal with a homogeneous product so that no individual has any perceptible influence on the market. This is an abstract world that does not exist. The monopolistic and imperfect competition theories show how monopolies could raise prices above the competitive equilibrium to produce a permanent monopoly profit. This leads economists toward a greatest willingness to accept government antitrust policies and regulation of public utilities, and reverse the trend toward big business. But even without monopoly profit, prices are likely to be higher and output lower than under perfect competition, and monopolistic or imperfect competition theory has no solution. "Workable competition" has replaced pure competition as the goal, a compromise between pure competition and oligopoly. (Note: A monopoly is one firm, duopoly is two firms, and an oligopoly is two or more firms).

The theory of monopoly was developed by Augustine Cournot in 1838, nearly a hundred years before the work on monopolistic competition was published.

Cournot

Antoine Augustin Cournot (1801-1877) was a French mathematician who published papers on mathematics, philosophy, and economics, and the first to apply math to economics. Cournot developed a system of equations to illustrate general equilibrium, and defined and described the down-sloping demand curve. He also proved that the equilibrium price is where the quantity supplied is equal to the quantity demanded. Increasing returns or decreasing costs as the scale of a firm increases, will increase their advantage over smaller competitors and lead to monopoly. Seeking maximum profit, the monopolist will select the combination of price and quantity that will provide the greatest profit.

Cournot's theory of duopoly included a step-by-step adaptation of output by each producer to obtain a stable equilibrium with each duopolists selling equal quantities at a price that was above the competitive price, but below the monopoly price. If there was collusion among the duopolists, they would charge the monopoly price. Cournot developed a case with two proprietors who each owned a mineral spring that provided waters that were perfect substitutes for each other. He assumed that there were no cost of production, and price times sales quantity was equal to their respective incomes. Total sales was a function of price, and price was a function of total sales. Using calculus and a graphic illustration he demonstrated that the quantities sold by both duopolists would be equal based on the assumed conditions.

Although Cournot has been criticized for his unrealistic assumptions and omission of many other possible solutions, he was a pioneer in developing a theory of imperfect competition, as well as a theory of pure competition.

Sraffa

Piero Sraffa (1898-1983) was the editor of Ricardo's collected works and correspondence. He published an article (The laws of returns under competitive conditions) in the 1926 issue of the Economic Journal that helped stimulate a critique of the theory of pure competition. Sraffa pointed out that the unit costs of production may decrease as a firm increased its scale of production because of internal economies or because overhead costs are spread over a larger number of units. This is incompatible with pure competition. Although pure competition and monopoly are extreme cases, two forces are frequently found in industries where competitive conditions prevail that break up the unity of markets. A single producer can affect market prices by varying the quantity supplied, and each producer may produce with decreasing unit costs. These conditions are more in line with monopoly than pure competition, and are derived from the fact that the producer faces a down-sloping rather than a horizontal demand curve.

For business men who are subject to competitive conditions, the main obstacle to increasing production is not increased cost, but the difficulty of selling a larger quantity without reducing the price or incurring additional marketing expenses. Each producer enjoys special advantages, or monopoly elements in his own market. If he raises his price, he will not lose all his business, and if he lowers his price he will not take away all his competitor's business. His demand curve slopes downward to the right. Buyer preferences for a particular firm's product may be caused by long custom, personal acquaintance, confidence in the quality of the product, proximity, obtaining credit, or other factors that distinguish it from the products of other firms. When each firm producing a commodity is in such a position, the market is subdivided into a series of distinct markets and each firm obtains advantages that are equal to those of the monopolist.

In a stable industry, a firm can lower its price and increase its sales and profits. A more acceptable way for a firm to increase its profits is to raise prices without injuring competition. Rival firms gain from the increase in prices and are not provoked to retaliate.

Chamberlin

Edward Hastings Chamberlin (1899-1967) was a Harvard professor who published The Theory of Monopolistic Competition in 1933. Chamberlin combined the theories of monopoly and pure competition and attempted to explain the wide range of possible market situations that are in between these two extremes. A key concept of monopolistic competition is that the firm's demand curve in down-sloping causing the marginal revenue curve to lie below the demand or average revenue curve. Chamberlin was one of the first to discover and apply the idea of marginal revenue, i.e., the addition to total revenue from selling an additional unit of output. Under pure competition, marginal revenue is equal to price since the firm can sell all it produces at the going market price. Both demand and marginal revenue curves are horizontal lines.

With a down-sloping demand curve, the marginal revenue curve will also slope downward, but more steeply than the demand curve. For example, if a entrepreneur can sell one pair of shoes per day for $20, two pair per day for $18, and three pair per day for $16, the marginal revenue from selling the third pair is $12 or 3x$16 less 2x$18.

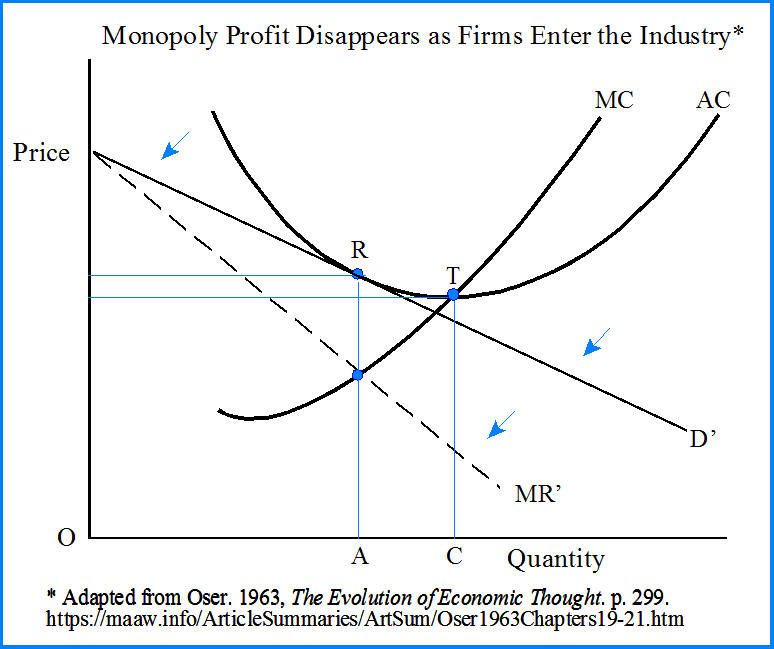

Marginal cost is the addition to cost as a result of producing one more unit of output. The marginal cost curve crosses the average cost curve at its lowest point. The profit maximizing output for each firm is where the marginal cost and marginal revenue curves intersect, i.e., where marginal revenue is equal to marginal cost. At that point, the price will be BN, output will be OB units, and the extra profit will be LSNM as illustrated in the graphic below. If the firm has long-run monopoly power, e.g., can exclude new firms from entering the industry, this will represent the long-run equilibrium for the demand and cost structure illustrated, and the extra profit is monopoly profit.

Where there are many firms under monopolistic competition, free entry into the industry will cause monopoly profits to disappear. In the long-run the demand curve will fall to D', OA will be produced, and sell for AR per unit as illustrated in the revised graphic below.

According to Chamberlin, if we assume pure competition exits in the industry, the demand and marginal revenue curve would be horizontal and identical. OC units would be produced and sell for the price indicated by CT. Chamberlin concluded that the price would be higher and the scale of production smaller under monopolistic competition than under pure competition, and this would result in excess productive capacity. However, an underlying assumption is that the cost curves would be the same in each situation which is unrealistic. The cost curves of a small firm in pure competition would be far above those of giant firms. Therefore pure competition would not necessarily provide the largest volume of output and the lowest prices.

Robinson

Joan Violet Robinson (1903-1983) was a professor of economics at Cambridge University and a student of Alfred Marshall. Robinson's book The Economics of Imperfect Competition was published in 1933 shortly after Chamberlin's book appeared, and covered the same concepts. She added to monopoly the concept of monopsony, or a market with a single buyer. One case of a monopsony would be where all the buyers of a commodity form an agreement to act together. Assuming both the combined demand curve, and supply curve remain unchanged, the buyer under monopsony will increase his purchases up to the point where marginal cost is equal to marginal utility. If an industry is experiencing increasing or decreasing supply price, marginal cost to the monopsonist will not be equal to the price of the commodity. In such cases the monopsonist will buy less or more than under competition. For example, if suppliers are pushed beyond their lowest-cost output, the industry supply curve (average cost) would be up-sloping, and the marginal cost curve would lie above the average cost curve as illustrated the graphic below. With monopsony, OA would be purchased at price AR per unit (average cost) where the buyer's marginal utility (represented by the demand curve) is equal to marginal cost. Monopsony profit would be LRNM. If a competitive market existed, rather than monopsony, OB would be purchased at a price of BS.

Robinson also analyzed the productivity theory of distribution in imperfect competition. Using labor as an example, the marginal physical productivity of labor is the output produced from employing an additional unit of labor with a fixed quantity of other factors. This she said will decrease as more workers are employed because of diminishing returns. Where demand is not perfectly elastic (horizontal), the firm has to lower its price to increase sales. Exploitation occurs where the wage is less than the marginal physical product of labor valued at the selling price. Robinson concluded that exploitation of labor occurs under both monopsony in buying labor, and under monopoly or imperfect competition in selling the products produced by labor. The remedy for exploitation under monopsony would be a minimum wage imposed by a trade union or trade board. To eliminate exploitation under monopoly the selling price would have to be controlled to be equal to average cost.

Later Robinson wrote that her book and other similar economic theory failed to deal with time. Although a system moves toward equilibrium, equilibrium also moves before it can be reached, so there is no such thing as long-run equilibrium. She went on to develop a more realistic analysis of the economic world after Oser's book was written.

Chapter 21: Welfare Economics and Social Control

Welfare economics cannot be called a school because it does not represent a unified system of ideas. It is instead an area of economic thought that interests economists from various schools. It raises questions about how the economy functions, the adequacy of its system of distribution, and to what extent the laissez faire system needs to be regulated to promote welfare. Liberal economists have argued that laissez faire requires government intervention to produce more equitable results, and their ideas are permeated with value judgments. Most liberal economists agree that laissez faire does not produce the best results, and that some government intervention is necessary, but they disagree about how much is required. The conservative view is that too much regulation toward the redistribution of wealth and income may destroy the ability to accumulate income and kill the incentives to invest. They argue that it is only through the pursuit of profit, and an unequal distribution of income that maximum growth is possible. The most impartial economists make value judgments such as: price stability is a good thing, rising national income is desirable, the allocation of resources through competition and consumer choice provides the best results, productivity is the most ethical basis for rewards, and increased productivity is applauded. The different views of economists related to welfare economics and social control are mainly based on the degree to which their value judgments are recognized and accepted, and their degree of reliance on individualism and laissez faire, as opposed to collective or communitarian social regulation over the production, distribution, and consumption of wealth.

Hobson

John Atkinson Hobson (1858-1940) was a journalist, popular lecturer, and author of thirty-seven books. One of his major themes was the interdependence of politics, ethics, and economics. Imperialism was one of his most famous books. He rejected the classical and neoclassical ideas that pure competition was the typical competitive market situation, that a harmony of interest existed, and that laissez faire was the best economic policy. He developed a program of reform, mainly through government intervention, that he referred to as welfare economics.

Oser discusses three strands of Hobson's thought:

1. That underconsumption and oversaving leads to overinvestment,

2. That the inability to keep the economy fully employed leads to imperialism, and

3. That there should be greater equality of income for ethical reasons and to increase consumption spending.

Hobson stated that the central problem in society was the recurring unemployment of labor, capital, and land. He did not accept the classical doctrine that the more thrifty a nation, the more wealthy it becomes. An increase in capital requires a subsequent increase in consumption of the commodities that the capital will produce. To answer the question of why there could be too much saving and not enough consumption, Hobson developed a theory of income. Income received by labor includes two parts: one increment for maintenance or subsistence, and an another increment for growth in the economy. If wages are above the level to cover subsistence and the cost of growth, the remainder will be an unproductive surplus or unearned increments. Wages are too high and unproductive if they do not induce a greater supply of labor. Likewise, if interest and profit are above the level required to maintain worn out capital and produce a healthy growth of capital, the surplus will be unproductive and unearned. Genuine economic rent on land is also an unproductive surplus. Failures of competition to work effectively toward raising wages and lowering property incomes cause too much saving and not enough consumption. The rich save too much of their incomes because they are motivated to invest and accumulate wealth. Saving is socially useful up to a point, but if the rate of saving is too high, unemployment will occur. On the other hand if savings are too low, productive capacity will be wasted, and the future will be sacrificed to the present.

The business cycle is caused by underconsumption and oversaving. Prosperity causes prices, capital investment, and bank credit to increase. A weakening of prices is the first symptom of a coming depression. Profit margins decline, banks curtail credit, pessimism spreads, and bank depositors and investors seek to withdraw funds. The financial collapse is caused by the imbalance between consumption and saving. The trend is reversed when incomes fall reducing savings enough to produce a new balance.

Oversaving and underconsumption leads to imperialism since an abundance of goods that cannot be sold at home can be sold or unloaded in the colonies. However, if income is distributed properly, the market at home could be expanded and the motivation to exploit the colonies would become unnecessary. The remedy for oversaving, underconsumption, depression, and imperialism is a more equitable redistribution of income that would reduce the proportion of saving to consumption spending. This would increase demand and stimulate industry, promote full and more stable employment. The absolute quantity of saving would be as large as before, but it would be smaller in relation to total income.

A more equitable distribution of income could be accomplished with union action to raise wages, pensions, and other benefits, or through government regulation of industry, operation of industry, and taxation to raise revenue for public consumption. Examples of government regulation include minimum wage enactments, workmen's compensation laws, limited hours of labor, and improved sanitation. Government operation of industry is applicable where monopolies produce large surplus profits in industries such as transportation, communication, mineral resources, banking, insurance, water, gas, and electricity. This kind of socialism would still include large areas in the economy that were based on private enterprise to promote individual initiative. Unskilled industries provide the right environment for socialism, while skilled industries are more compatible with private enterprise. When incomes are too high in the private enterprise system, the state should tax away the surplus. The money received by the state should be used to provide social services such as health and education.

Hobson argued that the standard of human well-being should replace the orthodox economists' monetary standard of wealth. We should ask questions such as: What are the net human cost involved in production, and what are the net human utilities involved in their consumption? His idea was to minimize human cost while maximizing human utility.

Pigou

Arthur Cecil Pigou (1877-1959) succeeded Marshall (See Chapter 14) as the chair of political economy at Cambridge University in 1908. Like Marshall, Pigou was concerned about the conditions of the poor, but was more inclined to allow a role for the government in improving certain undesirable features of society. Pigou abandoned the orthodox idea that what was good for the individual was good for society, or that total welfare was the summation of all individuals' welfare. In The Economics of Welfare originally published in 1920, Pigou wrote that increasing the share of real income in the hands of the poor would, in general increase economic welfare.

Pigou made a distinction between social and private marginal cost and benefits. Private marginal cost is the expense the producer incurs in making an additional unit, while social marginal cost is the expense or damage to society that results from producing that unit. Private marginal benefit is equal to the selling price of the product, while social marginal benefit is the total benefit to society from the production of an additional unit. Social costs may be greater than private costs causing the private marginal net product to exceed the social marginal net product. For example, where an entrepreneur builds a factory in a residential district, much of the value of other people's property would be destroyed. Selling intoxicating beverages is profitable to the distiller and brewer, but increases the social cost when more policemen and prisons become necessary as a result. The opposite case occurs when the benefits of private actions spill over to society, and the people responsible are not compensated for the benefits. In such cases the social marginal net product will exceed the private marginal net product. For example, a factory's investment to reduce smoke from its' chimneys will benefit the community more than it benefits the factory owner.

In general, industries where private cost are too low (i.e., where private gain is high) tend to grow too large, and industries where private cost are high and private gain is low remain too small. This may result in too much investment and employment in sweated industries and too little in schools and hospitals.

Pigou recognized that advertising was another cause of differences between social and private net products. Although advertising provides a social purpose in being informative, much of it is strictly competitive, and its social net product is zero or negative.

Another problem for society occurs because of people's cavalier attitude towards the future. Efforts directed toward the remote future are starved in relation to efforts directed toward the near future, and these are starved relative to efforts directed toward the present. Natural resources are consumed wastefully because future satisfactions are underrated. Government intervention should not strengthen the tendency for people to devote too much of their resources to the present and too little of their resources to the future. As a result, a tax on saving, property taxes, death taxes, and progressive income taxes should be condemned to maximize economic welfare. Heavy taxes on consumption are preferable, except for the need to balance equity toward low-income people against the desirability of increased saving. In contrast to the views of Hobson, Pigou wanted to increase saving to promote economic growth and he did not view excessive saving as a problem.

Where private and social net products do not coincide, government intervention can increase welfare. The government should bring private and social net cost into equality by subsidies, taxes, and legal regulation, e.g., taxing alcoholic drinks and competitive advertising, zoning laws, and subsidies to research. Pigou insisted that legitimate interpersonal comparisons of satisfactions could be made with typical people of the same race that grew up in the same country.

Clark

John Maurice Clark (1884-1963) was the son of John Bates Clark (See Chapter 13), and a professor of economics at Columbia University. He worked toward a synthesis of neoclassical and institutional economics, and was a forerunner of the Keynesian system. In 1917 he published a famous article in the Journal of Political Economy, "Business Acceleration and the Law of Demand" where he developed the relationships between changes in demand for final goods and the accelerated changes that they cause in the demand for machinery and raw materials. Clark published his classic, Studies in the Economics of Overhead Costs in 1923, Social Control of Business in 1926, and Strategic Factors in Business Cycles in 1934. In Clark's system of social economics, social control is required to serve the general welfare. In a journal article published in 1916, "The Changing Basis of Economic Responsibility" he wrote that ..."laissez-faire economics may well be characterized as the economics of irresponsibility, and the business system of free contract is also a system of irresponsibility when judged by the same standard."

In Studies in the Economics of Overhead Costs, Clark made a distinction between the individual and social points of view stating that variable cost for the firm is an overhead cost from society's standpoint. Labor is a fixed asset of the nation, and failure to use it represents as much of a loss as a failure to use a manufacturing plant. Social cost accounting would show a gain from employing labor in a slack season, while private accounting would show a loss. If wages were converted into an overhead cost for the firm, production would become more regular. This might be accomplished by a guaranteed annual wage.

The overhead cost of a producer becomes variable cost to the next firm in a process, or to a distributer. This shifting of cost distorts economic calculations related to the economic value of producing goods. The incentives of each producer are measured by his own overhead costs, not by the total overhead cost involved in the whole process from beginning to end.

Solutions to economic problems require a coordinated effort by government, banking, industry, insurance, and labor. Individual firms should plan steadier production over the business cycle to avoid a slump during a depression. In addition, social and government programs should be used to promote stability.

Although many social controls had been exacted, Clark conceded that the existing system was far from perfect from the perspective of efficiency. A democratic collectivism is not the answer because it would sacrifice efficiency and technical progress, and reduce personal liberty. But the argument against collectivism should not be taken as an argument for preserving the existing system. It is an argument for continuing to struggle to balance liberty and control, and to reduce our worst evils to tolerable levels. There are no quick cures for basic evils, but it is conceivable that we could obtain enough coordination to reduce unemployment to a minimum and maintain stability without making everyone an employee of the state. It would make little difference whether we called it socialism or not. Such a system could still be democratic and leave room for personal liberty.

__________________________________________

Go to the next chapter. Chapter 22: The Keysnesian School (Summary)

Go to Chapter 1 and the links to all Chapters. (Summary).

Related summaries:

Martin, J. R. Not dated. A note on comparative economic systems and where our system should be headed. (Note).

Milanovic, B. 2019. Capitalism, Alone: The Future of the System That Rules the World. Harvard University Press. (Summary).

Piketty, T. 2014. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Belknap Press. (Note and Some Reviews).

Porter, M. E. 1980. Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors. The Free Press. (Summary).

Porter, M. E. and M. R. Kramer. 2011. Creating shared value: How to reinvent capitalism and unleash a wave of innovation and growth. Harvard Business Review (January/February): 62-77. (Summary).

Thurow, L. C. 1996. The Future of Capitalism: How Today's Economic Forces Shape Tomorrow's World. William Morrow and Company. (Summary).