Summary by James R. Martin, Ph.D., CMA

Professor

Emeritus, University of South Florida

Pricing Decisions Main Page |

Surveys Main Page

According to Warren Buffett. "The single most important decision in evaluating a business is pricing power." Although competition, costs, and market price sensitivity affect the parameters of a company's pricing strategy, pricing power is a learned behavior or skill that can be developed within an organization. The purpose of this paper is to describe the five major categories of pricing capability, the two dimensions of these capabilities (price orientation and price realization), the characteristics of the five zones, and the transformation process for improving a company's pricing capability.

Price Setting or Orientation

Pricing strategies or orientations generally fall into three categories: Cost-based pricing, competition or market-based pricing, and customer value-based pricing. Hinterhuber's description of these strategies is provided in the illustration below from my summary of his 2008 article: Customer value-based pricing strategies: Why companies resist. (Summary).

Price Getting or Realization

Price realization refers to the capabilities and processes a company uses to get the price that the company sets, e.g., avoiding inconsistent discounting and other undesirable behavior by sales personnel. Price realization requires establishing pricing rules and procedures to insure that the rules are followed so that list prices become realized prices.

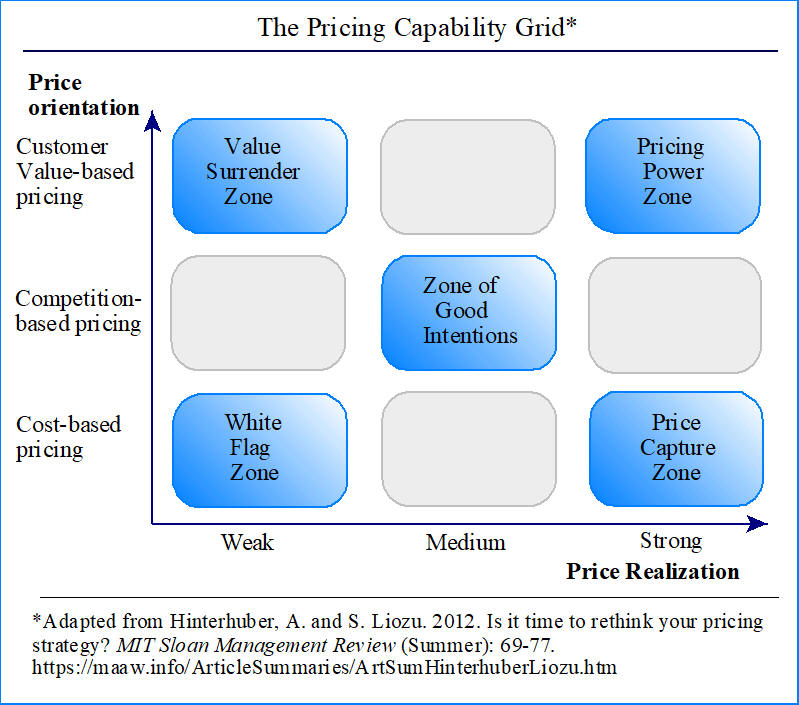

The Pricing Capability Grid: Five Primary Zones of Pricing

To determine the current state of pricing practice in U.S. companies the authors interviewed 44 managers in 15 U.S. based industrial companies over an 18 month period. To measure the degree these companies had developed their pricing function, the authors developed a pricing capability grid that includes five major categories. These five primary categories or zones of pricing are illustrated in the following grid.

1. Pricing power zone: Companies in this zone have high capabilities in price orientation and price realization. They have the ability to command significantly higher prices and profitability than other companies. These companies have a culture dedicated to pricing, customer value analysis tools, robust pricing processes, champions and other executives responsible for pricing. These executives and the support and conviction from top leaders drives customer value-based pricing throughout the company.

2. The white flag zone: Companies in this zone have low capabilities in price orientation and price realization. They pay little attention to pricing and realize lower prices and profitability than other companies. Their prices are cost-based and do not reflect the customer's value and willingness to pay. Their discounting is widespread and chaotic. They essentially abdicate their pricing power to customers.

3. The value surrender zone: Companies in this zone have high capabilities in price orientation, but weak capabilities in price realization. List prices generally reflect customer value, but discounting prevents the companies from achieving the value they have created. Sales personnel negotiate prices, but do not have the information and skills needed to improve price realization.

4. The price capture zone: Companies in this zone have low capabilities in price orientation, but high capabilities in price realization. They have strong systems and processes to minimize unjustified discounting from list prices, but the list prices are generally cost-based and do not reflect the full value their products deliver to customers.

5. The zone of good intentions: Companies in this zone have an average price orientation, and average price realization capabilities. These companies use more advanced approaches in setting prices such as linking their prices to a well-defined group of competitors. They also have systems to encourage discipline to achieve price realization.

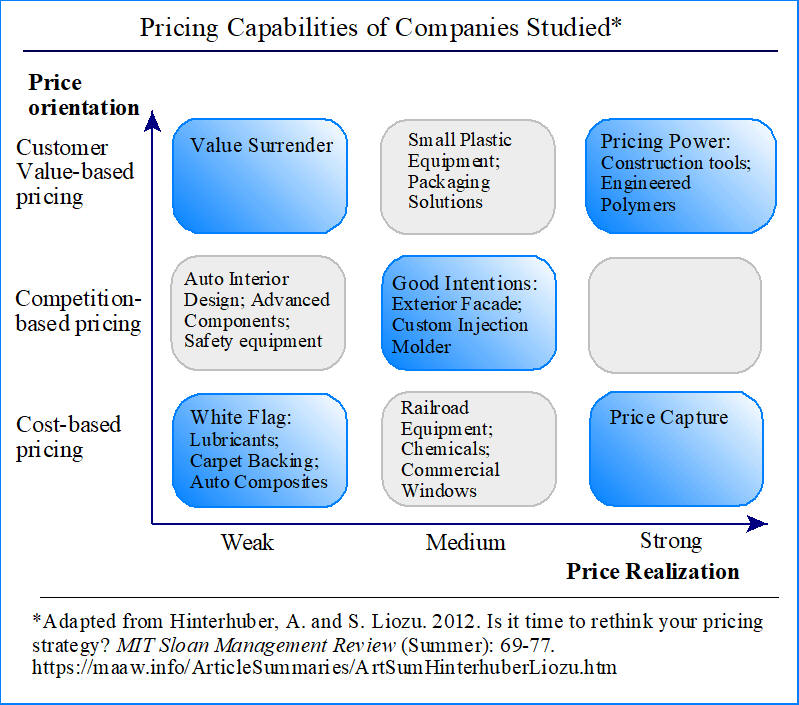

Pricing Capabilities in the Companies Studied

The pricing capabilities of the fifteen companies studied are illustrated in the graphic below. Only four used customer value-based pricing, and only two were categorized in the pricing power zone. Five firms used competitive-based pricing but all of these experience limited price realization. Six firms used cost-based pricing and none of these firms had the capability to obtain strong price realization.

The Transformation to Strong Price-Orientation and Price-Realization Capabilities

Few companies have made the transition from cost or competition-based pricing with weak price-realization to customer value-based pricing with strong price-realization capabilities. This transformation requires a deep organizational change that requires a gradual and sometimes painful process. The transformation requires that new value-based concepts are embraced by everyone involved in the price orientation and price realization process.

How to Rethink Your Pricing Strategy

The first step involves rethinking a company's pricing strategy recognizing that a customer value-based pricing orientation provides the best overall approach to pricing. The second step is to develop or improve the process of translating list prices into realized prices. Implementing value-based pricing and price realization controls is not easy and will often require improvements in a company's information systems, negotiation capabilities, incentive systems, controlling tools, and sales personnel confidence. It will also require top management support and involvement to change the company's culture. These transformational changes are difficult to obtain, but they are the key catalysts needed to obtain pricing power and enhanced profitability.

________________________________________

Related summaries:

Abel, R. 1978. The role of costs and cost accounting in price determination. Management Accounting (April): 29-32. (Summary).

Bertini, M. and O. Koenigsberg. 2021. The pitfalls of pricing algorithms. Harvard Business Review (September/October): 74-83. (Summary).

Dummer, W., M. Masters and D. Swenson. 2015. Delivering customer value through value analysis. Cost Management (March/April): 17-24. (Summary).

Govindarajan, V. and R. N. Anthony. 1983. How firms use cost data in price decisions. Management Accounting (July): 30-31, 34-36. (Summary).

Hinterhuber, A. 2008. Customer value-based pricing strategies: Why companies resist. Journal of Business Strategy 29(4): 41-50. (Summary).

Hughes, S. B. and K. A. Paulson Gjerde. 2003. Do different cost systems make a difference? Management Accounting Quarterly (Fall): 22-30. (Summary).

Martin, J. R. Not dated. Chapter 11: Conventional Linear Cost-Volume-Profit Analysis. Management Accounting: Concepts, Techniques & Controversial Issues. Management And Accounting Web. Chapter11.

Martin, J. R. 2022. A note on pricing strategies. (Note).

Porter, M. E. 1980. Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors. The Free Press. (Summary).

Shim, E. and E. F. Sudit. 1995. How manufacturers price products. Management Accounting (February): 37-39. (Note).

Shim, E. D. and R. Lim. 2022. A survey of U.S. firms' pricing strategies and costing methods. Cost Management (May/June): 15-19. (Note).

Thurston, K. L. D. M. Keleman and J. B. MacAarthur. 2000. Providing strategic activity cost information: Cost for pricing at Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Florida. Management Accounting Quarterly (Spring): 4-13. (Summary).