Chapter 11

Using Budgets to Achieve Organizational Objectives

Study Guide by James R. Martin, Ph.D., CMA

Professor Emeritus, University of South Florida

ABKY Main Page

In this chapter ABKY cover the budgeting process, the master budget, methods of forecasting demand, cost-volume-profit analysis for both single product and multi-product organizations, budgets for discretionary costs, and the behavioral aspects of budgeting.

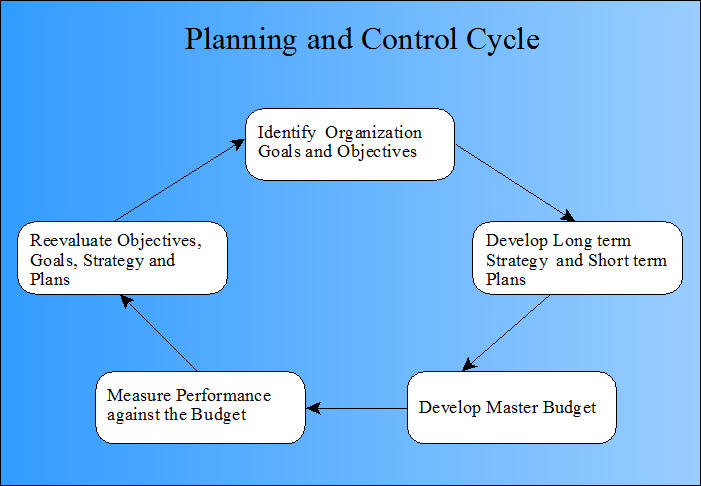

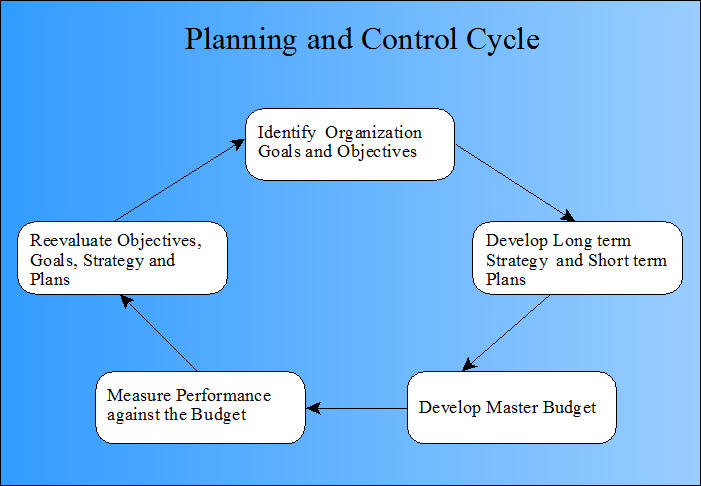

The overall concepts of planning and control are illustrated in ABKY Exhibit 11-1 and summarized in a similar exhibit below. After the organization's objectives, goals and strategy has been identified, the master budget is developed to express the plans in monetary terms. The master budget serves as a tool for communication and coordination recognizing the interrelationships within the organization. The control elements of the cycle involve calculating differences (variances) between the actual results and the budget estimates to help monitor performance. This control concept is covered in the Chapter 12.

There are two main parts, or sub-budgets within the master budget including the operating budget and the financial budget. The operating budget involves forecasting the demands for various types of resources including the variable or flexible resources and the intermediate term and long term capacity related resources. There appears to be some disagreement related to where the income statement and capital budget belong. ABKY place the income statement in the financial budget and put the capital budget in the operating budget. I believe they have that distinction backwards, although this is a minor difference. From my perspective (and most management accounting textbook authors), the operating budget begins with the sales budget and ends with the budgeted income statement. The financial budget includes the capital budget along with the cash budget and budgeted balance sheet. Collections and payments tie the operating and financial budgets together along with all the budgeted changes in balance sheet accounts. An overall view of the master budget appears in ABKY Exhibit 11-2. The exhibit below from MAAW's Textbook chapter 9 provides a similar view.

See MAAW's Textbook Chapter 9 illustration for a fairly simple master budget example.

Methods of Forecasting Sales or Demand

There are various methods of forecasting demand including the following:

1. Take a market survey with sales representatives.

2. Use statistical forecasting models to estimate the demand

function, i.e., schedule of quantities consumers are willing and able to buy at various prices. See the graphic illustration below.

3. Use a percentage based on recent trends in growth or decline.

Types of Cost in Relation to Cause and Effect

There are three main types of cost related to the three types of resources. These cost types can be defined in terms of cause and effect as indicated in the exhibit below.

| Type of Cost | Cause and Effect or Cost Benefit Relationship |

Cost Behavior | Examples |

| Discretionary | Relationships are difficult or impossible to define. Spending is at the discretion of management. | Fixed, variable and mixed in the short run. | Cost of administrative and support services such as employee training, advertising, sales promotion, legal advice, preventive maintenance, and research and development. |

| Engineered | Relationships are relatively easy to define. | Variable in the short run. | Flexible resources used in production activities such as direct materials and direct labor and many indirect or support resources such as electric power and supplies. |

| Committed | Relationships can be estimated, but not defined precisely. | Fixed in the short term and intermediate term. | Cost of establishing and maintaining the readiness to conduct business, such as the cost associated with plant and equipment. |

3. Cost Volume Profit Analysis

3a. CVP Analysis for Single Product Organizations

Cost volume profit equations are developed as follows.

Profit = Revenue - Total Costs

Profit = Revenue - total variable or flexible costs - total fixed or capacity related costs.

If we let P = sales price, X = units produced and sold, V = variable or flexible cost per unit and TFC = Total fixed or capacity related costs, then

Profit = PX - VX - TFC

Profit = -TFC + (P-V)X

or (P-V)X = TFC + Profit

X = (TFC + Profit) ÷ (P-V)

Where P-V is the contribution margin per unit and (P-V)X is the total contribution margin.

A graphic illustration of this linear CVP model appears below.

Ontario Tole Art Company Example

Ontario Tole Art Company's break-even point is

X = (TFC + Profit) ÷ (P-V)

X = (205,200 + 0) ÷ (80-17.60) from page 462.

X = (205,200 + 0) ÷ 62.40

X = 3,288.46 units.

We can show this graphically as in the figure below, adapted from ABKY Exhibit 11-16.

Determining the Units needed for a Target Profit

To find the number of units the company needs to produce and sell to obtain a target profit we simply include the target amount in the equation and solve for the unknown number of units. For example, if the desired target profit is $106,800, the needed units are found as follows.

X = (TFC + Profit) ÷ (P-V)

X = (205,200 + 106,800) ÷ 62.40

X = 5,000 units.

This solution is indicated above where the target revenue is easy to identify from the graph, i.e., PX = ($80)(5,000) = $400,000.

See MAAW's Example 11-1 for another CVP problem including a graphic illustration.

4. CVP Analysis for Multiproduct Organizations

When multiple products are involved we need to calculate a weighted average contribution margin per unit, where the weights are the proportions each product represents in the sales mix. Using the Princeton Company example on page 464, Exhibit 11-17 shows that the contribution margins are $14 for plastic valves, $15 for metal valves and $13 for specialty valves. The sales data in this example represents the expected or budgeted mix. The mix proportions are based on each product's sales divided by total sales. The calculations are as follows:

Weighted average CM = 14(500/1,325) + 15(425/1,325) + 13(400/1,325) = $14.0188792

The total fixed cost in this example is $20,400,000 and includes $9,400,000 manufacturing costs, $6,500,000 administrative costs and 4,500,000 business sustaining costs. Mixed units at the break-even point are calculated as follows:

Mixed X = (TFC + Profit) ÷ (Weighted P-V)

Mixed X = (20,400,000 + 0) ÷ 14.0188792 = 1,455,181 rounded to whole units.

Rounding contribution margin causes the answer in the text to be slightly different.

Then multiplying the mixed units by the mix ratios we obtain the number of units of each product needed at the break-even point.

Plastic valves = (500/1,325)(1,455,181) = 549,125 rounded

Metal valves = (425/1,325)(1,455,181) = 466,756 rounded

Specialty valves = (400/1,325)(1,455,181) = 439,300

rounded

The number of units needed to produce a target profit can be determined by placing the target amount in the equation above and then solving for the mixed units and individual units as illustrated above.

What if and Sensitivity Analysis

What-if analysis involves determining the effects of various types of changes in the CVP model. These effects can be determined by simply changing the constants in the CVP model, i.e., prices, variable cost per unit, sales mix ratios etc. As ABKY point out, this is fairly easy with spreadsheets, or other software developed to handle these calculations. Sensitivity analysis is similar, but the idea is to test how sensitive the model is to bad estimates or forecasting errors.

Other Chapter Sections

There is a short section on the role of budgeting in service and not-for-profit organizations on pages 468-470 and a brief discussion of periodic versus continuous budgeting on page 470.

5. Controlling Discretionary Costs

Discretionary costs are controlled with the aid of appropriation budgets. Appropriation budgets establish a maximum amount that can be spent. The main differences between the various types of appropriation budgets are summarized in the table below.

Types of Appropriation Budgets

| Appropriation Budgets | |

| Type | Basis of Budget Amount |

| Incremental | Last year’s budget plus an increment. |

| Priority Incremental

(Not mentioned by ABKY) |

Last year’s budget plus an increment, but includes the manager’s priority of increases and possible decreases by activity. |

| Zero Based | Manager must supply detailed justification for the entire budget each budget period. In practice few budgets were ever zero based. Eighty percent based is more common. |

| Activity Based | Activity drivers are used to make more accurate estimates of future capacity needs and future costs. |

| Project Funding | Provides funding for projects with a specific time horizon or sunset provision. |

6. Behavioral Aspects of Budgeting

The last section addresses behavioral problems associated with budgeting. A great deal has been written about this topic. ABKY break it into two parts including: 1) the process of designing the budget and 2) the behavioral influences on the budget process.

Types of Budget Process Design

1. Authoritative - the budget is imposed from the top down.

2. Participative - Subordinates share in the budget decisions.

3. Consultative - Subordinates provide input, but are not involved otherwise.

1. Tight, but attainable - what is most likely to occur based on

efficient operations.

2. A Stretch - setting the budget targets well beyond previous performance.

3. Built in Slack - building

excess into the budget for contingences.

Behavioral Influences on the Budget Process

1. Budget gaming - dysfunctional behavior to achieve budget targets. (See the Collingwood and Jensen summaries for more on gaming).

2. Budget slack - building excess into the budget to reduce the risk of not meeting budget targets.

7. The Controversy Over Budgeting

(strong

This section is not part of Chapter 11, but very important.)

Budgeting is a very controversial topic and some authors recommend managing without budgets. For example, see the following publications and links.

Francis, A. E. and J. M. Gerwels. 1989. Building a better budget. Quality Progress (October): 70-75. (Summary).

Hope, J. and R. Frazer. 1997. Beyond budgeting ... Breaking through the barrier to "the third wave". Management Accounting. UK. (December). (See this article on the CAM-I Web site).

Hope, J. and R. Frazer. 2000. Beyond budgeting. Strategic Finance (October): 30-35.

Hope, J. and R. Frazer. 2003. Who needs budgets? Harvard Business Review (February): 108-115. (Summary).

Hope, J., R. Frazer and J. T. Trent. 2003. Beyond Budgeting: How Managers Can Break Free from the Annual Performance Trap. Harvard Business School Press.

Jensen, M. C. 2001. Corporate budgeting is broken - Let's fix it. Harvard Business Review (November): 94-101. (Summary).

Roehm, H., A. L. Weinstein, and J. F. Castellano. 2000. Management control systems: How SPC enhances budgeting and standard costing. Management Accounting Quarterly (Fall): 34-40. (Summary).

1. What is a budget? (See 2a above for a graphic view).

2. What is the difference between flexible and capacity-related resources? (See Chapter 3 terminology table).

3. A student develops a spending plan for a school semester. Is this budgeting? Why?

4. How does a family's budget differ from a budget developed for an organization?

5. What is a production plan? Give an example of one in a courier company. (See the budget diagram above).

6. What is a variance? How is a warning light in a car that indicates the oil pressure is low like a variance (or is it)? (See the budgeting process above and the Francis & Gerwels summary).

7. What is the difference between operating and financial budgets? (See the budget diagram above).

8. Would a labor hiring and training plan be more important in a university or a municipal government office that hires casual workers to do unskilled work? Why?

9. What is the relationship between a demand forecast and a sales plan? (See 2c above).

10. What is a demand forecast and why is it relevant in budgeting? (See 2c above).

11. Is employee training an example of a discretionary expenditure? Why? (See 2d above).

12. What does a capital spending plan do? (See committed costs in item 2d above).

13. What is an example of a capacity-related expenditure? (See Chapter 3 terminology table) and (Committed costs in item 2d above).

14. Are food costs in a university residence cafeteria an engineered cost or a capacity-related costs? Briefly explain.

15. Are materials always a flexible resource? Why?

16. What is a line of credit? How is it useful to a small organization?

17. Using the notion of aggregate planning, what problems would municipal authorities face when planning transportation for people attending a rock concert in the city's center?

18. What does the term contribution margin per unit mean? How is contribution margin used in cost analysis to support managerial decisions? (See items 3a and 3b above).

19. What does the term break-even point mean? (See items 3a and 3b above). (See MAAW's Example 11-1 for another CVP problem including a graphic illustration).

20. What are the similarities and differences between what-if and sensitivity analysis? (See the note on this above).

21. What is an appropriation? Give an example of one in a university. (See item 5 above).

22. What is a periodic budget?

23. You are planning your expenses for the upcoming school semester. You assume that this year's expenditures will equal last year's plus 2%. What approach are you using? (See item 5 above).

24. You are willing to donate to worthy organizations. However, you believe strongly that each request for a donation should be evaluated based on its own merits. You would not feel bad in any year if you donated nothing. What approach are you using? (See item 5 above).

25. What are the two interrelated behavioral issues in budgeting? (See item 6 above).

26. What are the three most common methods of setting the budget? (See item 6 above).

27. What is the most motivating type of budget with respect to targets? (See item 6 above).

28. What is a stretch target? (See item 6 above).

29. What is budget slack? (See item 6 above).