The Question of Reality: Summary of Chapters 3-7

Study Guide by James R. Martin, Ph.D., CMA

Professor Emeritus, University of South Florida

Chapters 1-2 |

Chapters 8-11 |

Chapters 12-15 |

Chapters 16-19 |

Chapters 20-22

Why is there anything rather than nothing? This chapter focuses on the Pre-Socratic philosophers attempts to understand the world in terms of one reality, i.e., what is the underlying reality that is revealed in the many things around us? This is referred to as the problem of the One and the Many. What is the untimate reality (the One)? And how is everything else (the Many) related to it?

The First Theory of Reality

Around 600 B.C. a man named Thales viewed reality as one thing. He lived in the city of Miletus (now Turkey) and he and his followers are called Milesian monists, i.e., one-ism. According to Thales, the one thing that represents the untimate reality is water. His reasoning for this view was that water is a necessity for all living things, it seemed to be present in most things, it seemed to be everywhere, there appeared to be more of it than anything else, and it could exist in different forms.

Three Pre-Socratic Traditions

Three broad Pre-Socratic traditions include the Ionian, the Italian, and the Pluralist.

1. The Ionian - Reality was identified with a sensible substance. Water, air, fire, or some indeterminate substance or mixture.

2. The Italian - Everything was viewed as essentially a number, or to some "being" was the one and immutable reality.

3. The Pluralists - Indentified reality with a plurality of substances, earth, air, fire, and water. Love and strife brought these elements together and separated them in an endless cycle. Other views in the Pluralists tradition were that all things are a mixture of an infinite number of divisible particles or seeds, or that everything arises out of an infinite number of irreducible atoms.

The Pre-Socratic philosophers had the notion of unity, a notion that there was an ultimate principle that governed the world as a system.

The first full-fledged philosophical system was developed by Plato (427-347 B.C.) who worked out a theory for all aspects of experience.

Plato and Socrates

Plato developed his theory from the ideas of Socrates, and he expressed his philosophy in numerous dialogues between Socrates and his contemporaries. In the dialogues, Socrates ask questions that cause the respondent to engage in an analysis that generates more and better answers. For example, a dialogue about holiness. The gods love holiness, but is holy holy because the gods love it, or do they love it because it is holy? In the Dialogues, Plato gradually introduced his ideas in place of those of Socrates even though Socrates is used as the mouthpiece. This makes it difficult to separate their ideas.

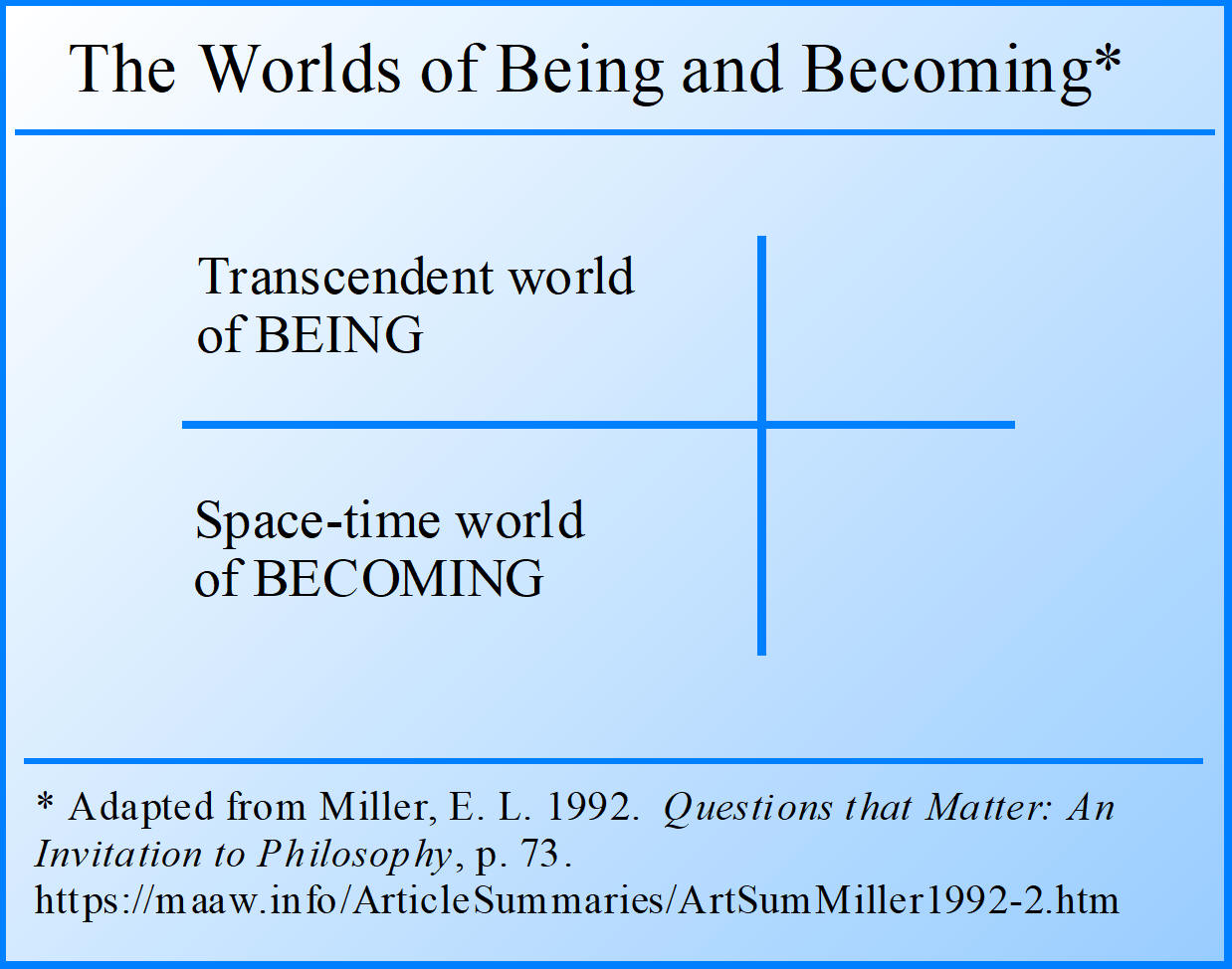

The Two Worlds: Appearance and Reality

The two-layer view of reality is that there is "what appears to be real," and "what is real." Plato used the terms Becoming and Being. For Plato, our understanding of being, truth, and goodness must be anchored in some objective, independent, and absolute reality. There must be a world of Being in addition to the world of Becoming. Becoming is a "twilight" or "half-way region" between reality and unreality.

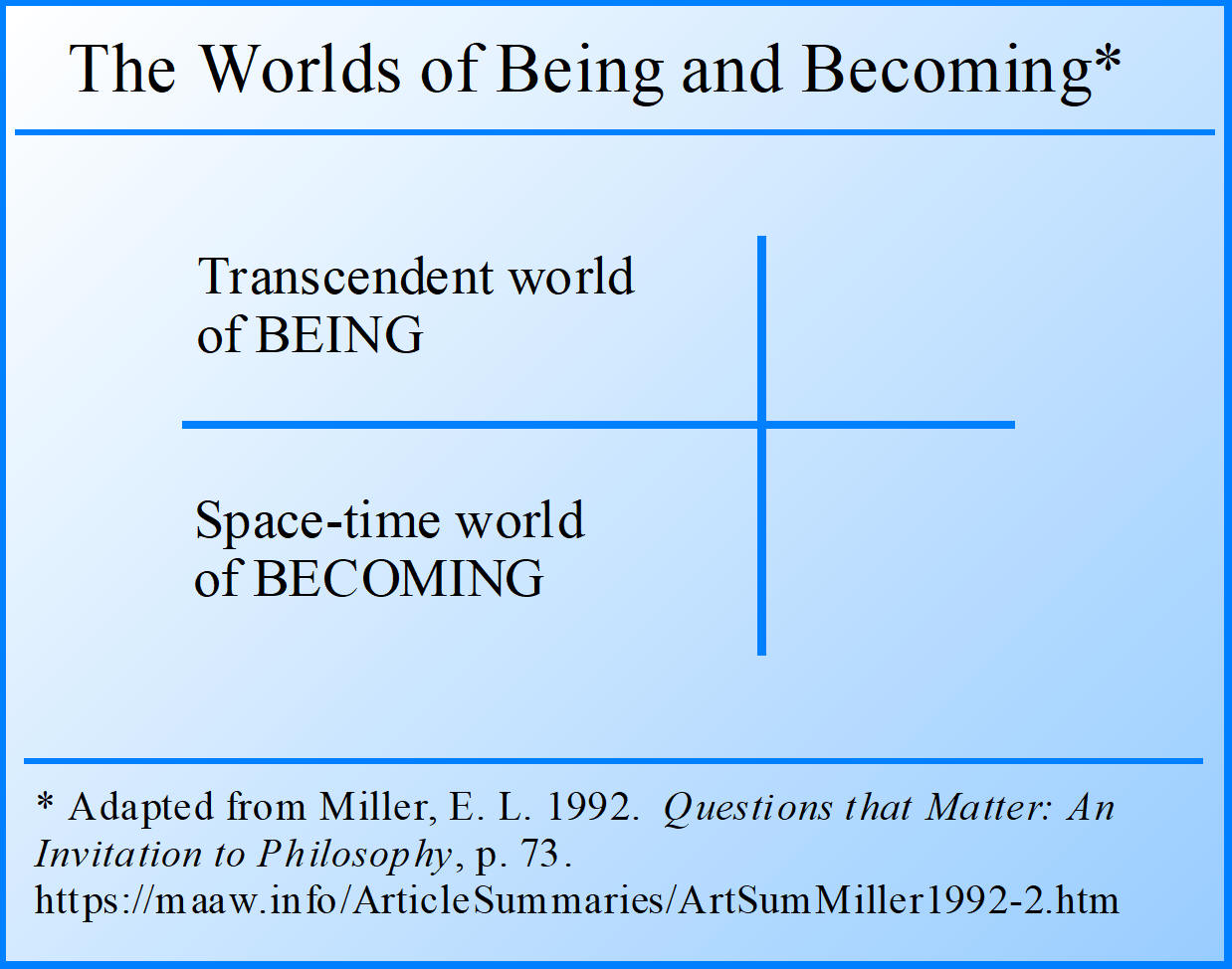

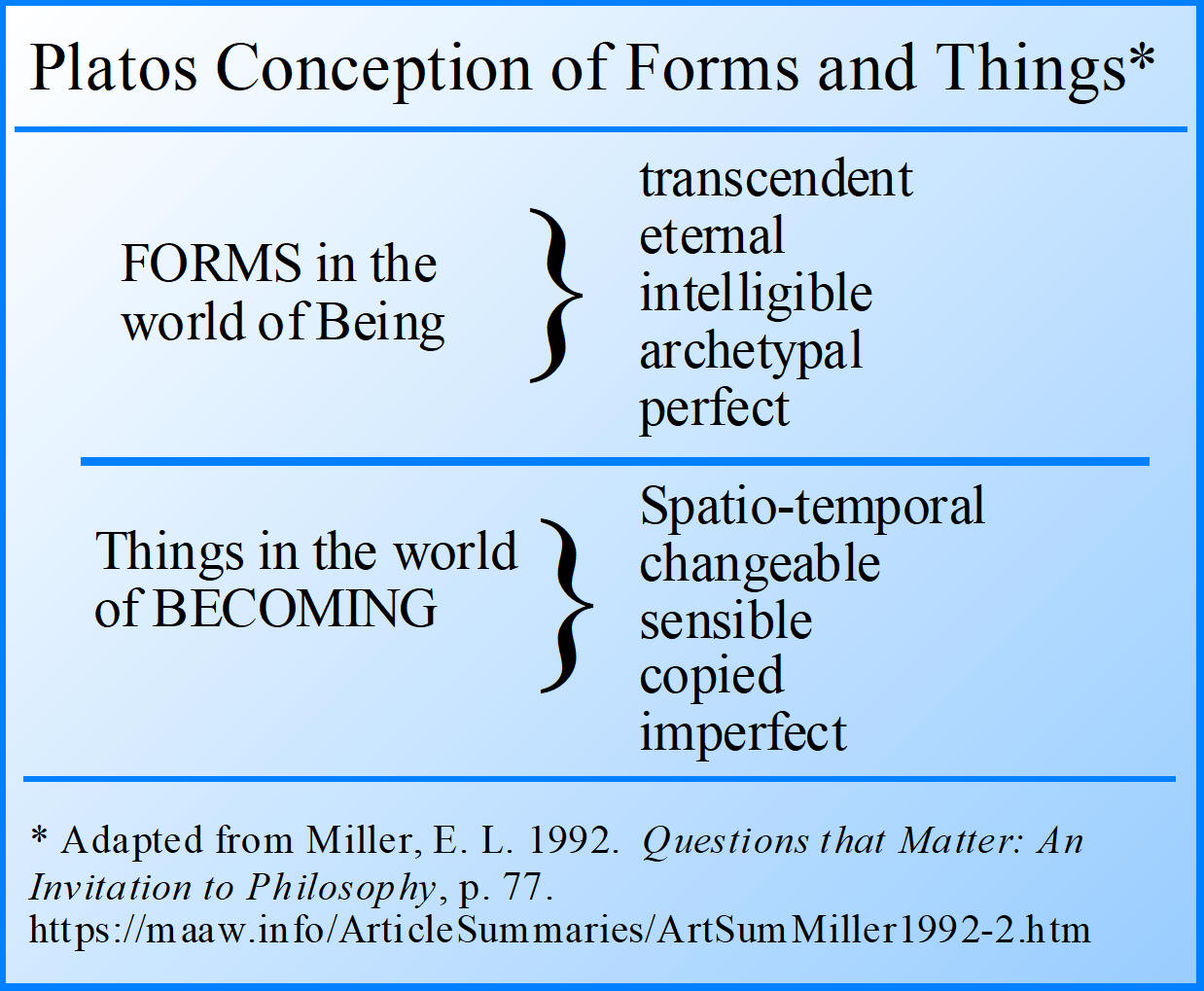

The Theory of The Forms

The world of Being is made up of realities called Forms (or Ideas). Forms are the causes of particular things that exist like tables, dogs, circles, human beings, instances of beauty, or examples of justice. Forms are:

Objective - they exist independently of our minds.

Transcendent - they lie above or beyond space and time.

Eternal - they are not subject to motion or change.

Intelligible - they cannot be grasped by the senses but only by the intellect.

Archetypal - they are the models for every kind of thing that does or could exist.

Perfect - they include absolutely and perfectly all the features of the things they represent.

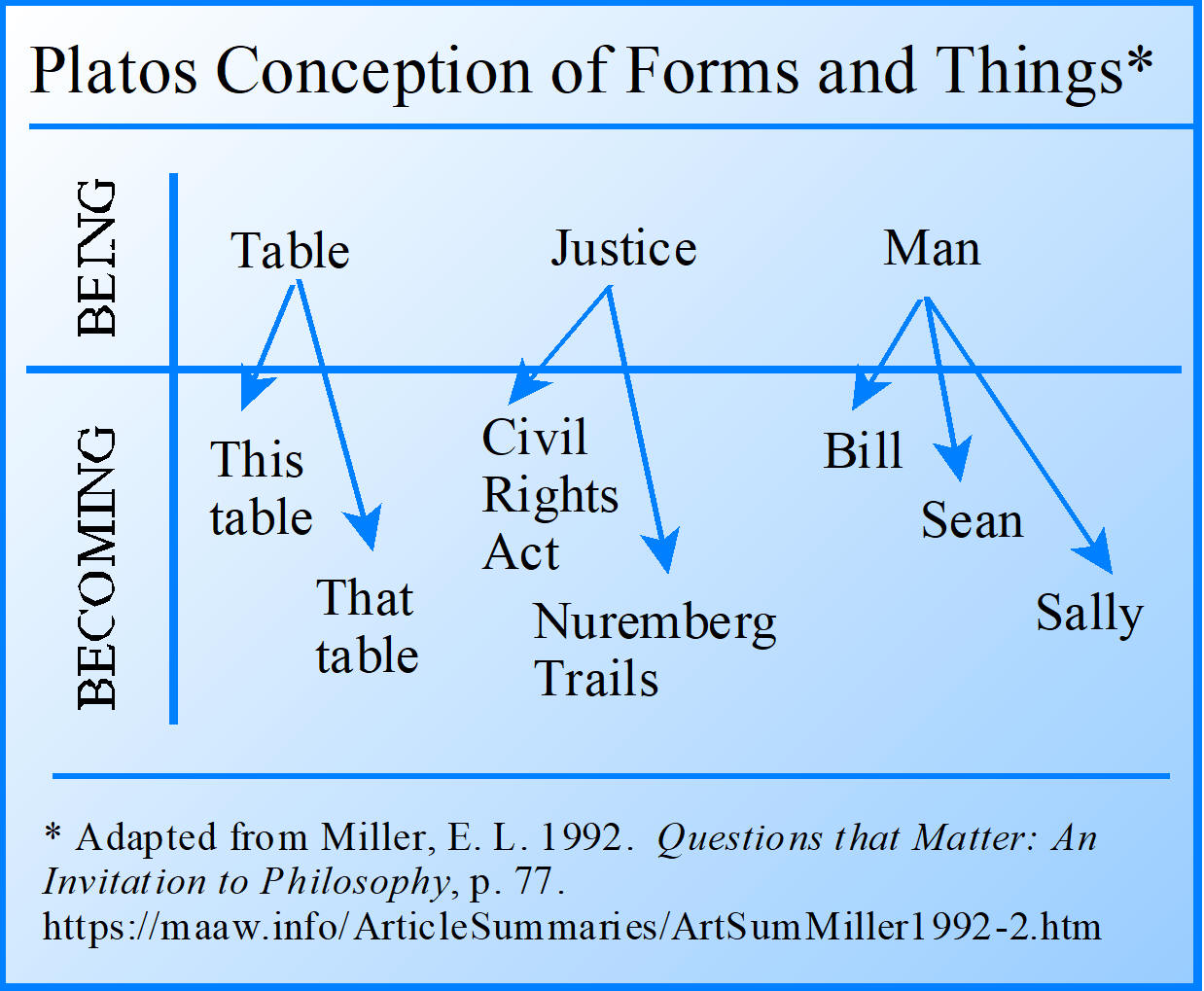

The theory of forms is that for every particular and imperfect thing in the world of Becoming (a table, an instance of justice, a circle, an example of beauty) there is a corresponding reality that is the essence or Form in the world of Being (Table, Justice, Circle, Beauty).

Plato was not precise on the nature of the Form's relation to the particular, and that things can participate in more than one Form. For example, things that live (dogs, cats, trees, humans) are part of the Life Form as well as their individual Forms. In addition, there are many different kinds of dogs, cats, trees and humans.

Degrees of Reality and Knowledge

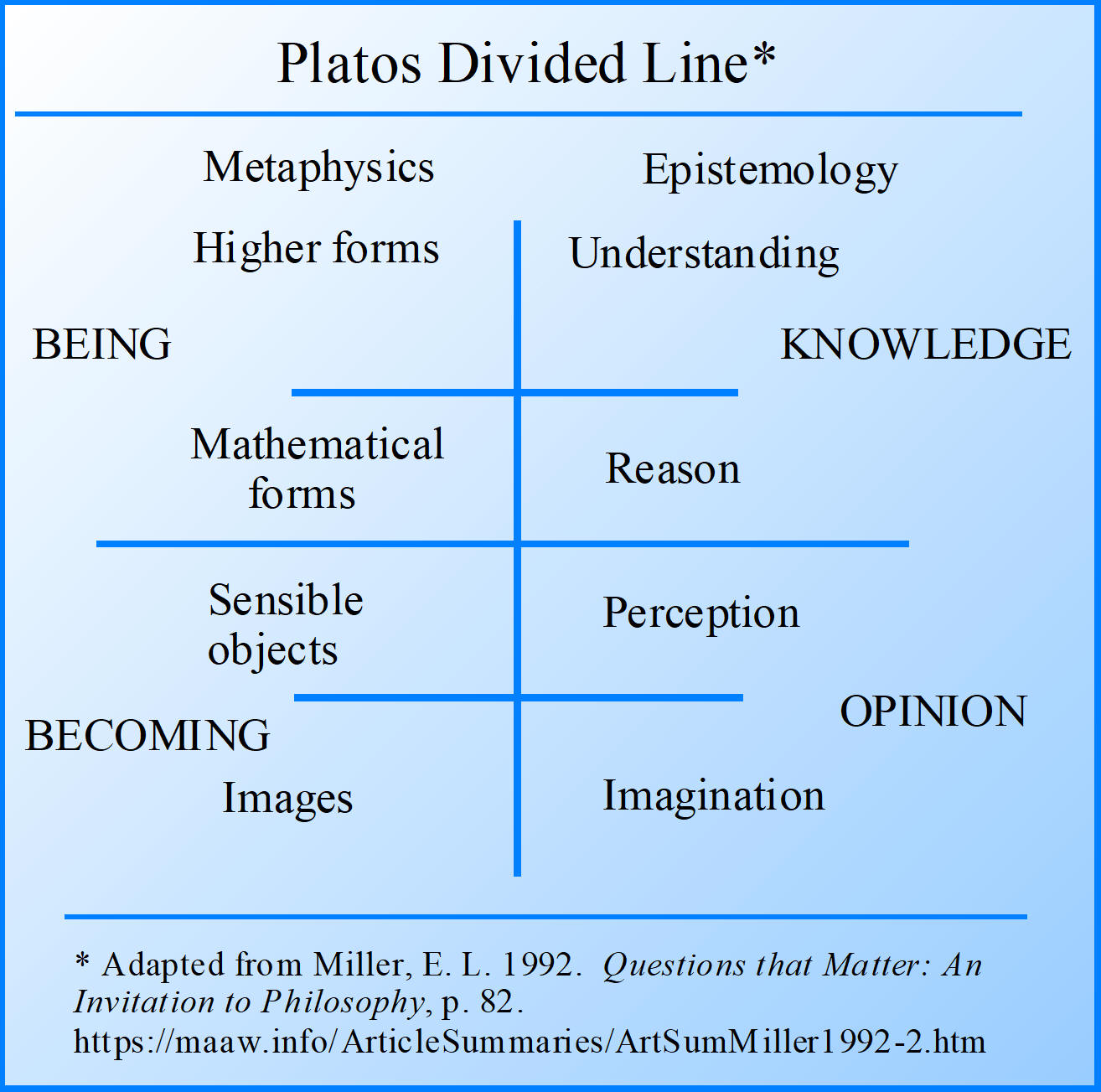

Plato's theory of reality is more complicated than the two layers of Being and Becoming. It involves a line divided into two unequal parts as represented by the graphic below.

Moving from the bottom to the top of the Line we attain greater and greater degrees of reality and certainty. The major division Line separates the world of Being and the world of Becoming. The lines above and below produce a ladder of reality on the lefthand or metaphysical side, and a ladder of knowledge on the righthand or epistemological side. The ladder of reality extends from images of things to the things themselves (tables, chairs, humans, etc.). The ladder of knowledge extends from mere imagination, to perception, to reason, to understanding.

The Good, The Sun, and The Cave

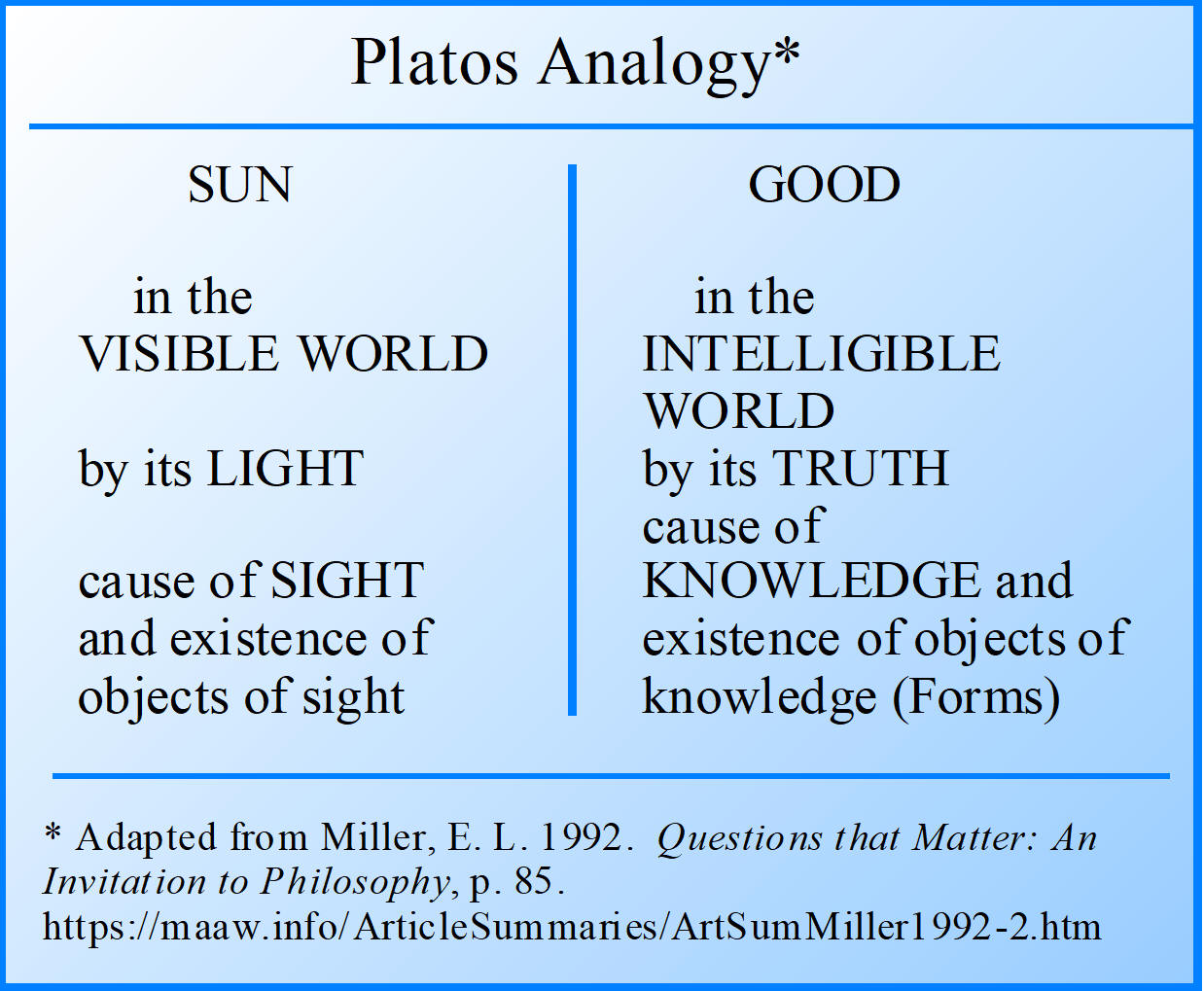

The essential Form of Good is above the Forms themselves. Plato's idea is that the Forms derive their being from a source that is above them, i.e., the Form of Good that is beyond being and knowledge. According to Plato the Good is to the intelligible world, or world of being, as the sun is to the visible world, or world of Becoming. Eyesight involves sight and objects to see, but also requires a third thing. The Sun or Light. The sun is analogous to the Form of Good and the visible world is analogous to Truth. The objects of sight are analogous to the objects of knowledge, and sight is analogous to knowledge.

The sun lights up the world and makes physical objects visible and further causes things in the world to exist and sustains them. The Good illuminates intelligible objects (Forms) and makes them knowable by the mind and is the ultimate principle of reality and truth. In the Allegory of the Cave, prisoners are chained to a wall in a cave so that they cannot move and can only see shadows on the wall of the cave facing them. They mistake the shadowy figures on the wall as reality. Only by forcing them out of the cave and into the light would they see what is real. The point of the story is that like the prisoners in the cave we mistake the unreal for the real, and that we might have to be forced to see truth and reality.

Aristotle's Criticism of Plato

Aristotle (a student of Plato) argued that Plato placed the ultimate causes of things (the Forms) in a transcendent world separated from the things they cause. How can the Forms be the causes of the nature of things without being in those things? They can't. How can the Forms account for the things around us coming into being? They don't.

Aristotle's View of Form

Aristotle rejected Plato's idea of transcendent Forms and instead used the idea of immanent Forms, i.e., Forms exist within particular sensible things. The Form combined with matter is what is real. "No form without matter, and no matter without form." This is called hylomorphic composition: Every thing in the natural world is composed of both matter and form. The exception was God who was viewed as the Unmoved Mover, the immutable source of all motion, who must be devoid of matter and therefore Pure Form.

According to Aristotle there are four principles, or causes of a thing:

Material cause - the matter,

Formal cause - its essence or whatness,

Efficient or moving cause - what brings it into being, and

Final cause - the purpose of the thing.

Lumping the last three together we have material cause/formal cause.

After Plato and Aristotle

Ockham's idea was that Forms have no external or independent existence. This view, referred to as nominalism is that Forms are merely names or words we use to group things together that have the same features. Another view is conceptualism, or the idea that there are universals but they are mind-made and used for the sake of meaningful thought and discourse about reality. "I can see the horse, Plato, but not horseness."

Adding these ideas we have three main mediaeval points of view regarding universals:

Realism - the doctrine of Forms, or essences, possess objective reality.

Nominalism - The doctrine that Forms, or universals are merely universal names that are used to group things that posses similar features.

Conceptualism - The doctrine that universals are mental constructs, and really exist in the mind.

Mind-matter dualism is a common view of reality. It is the belief that the mind might exist apart from matter. This reduces everything to two basic realities, i.e., mind and matter. Although the idea appears to be simple, mind-matter dualism is more complex than it appears.

Descartes: The Father of Modern Philosophy

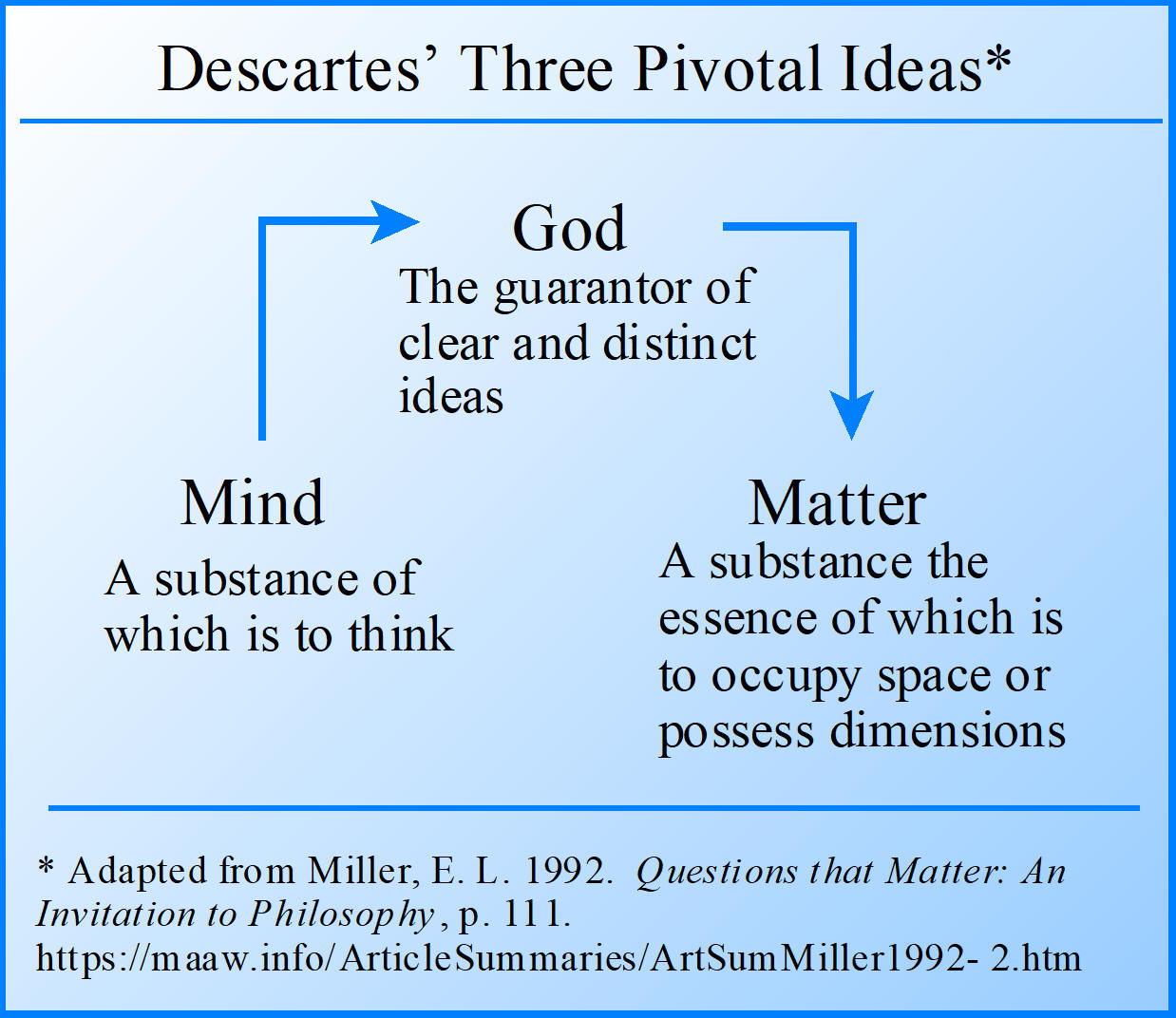

Rene Descartes (1596-1650) was a mathematician, scientist and philosopher who based his views on what could be known through reason (inside-out) rather than through the senses (outside-in). His philosophy was developed in three stages using intuition and deduction:

1. the knowledge of the mind,

2. the knowledge of God, and

3. the knowledge of matter.

What Can I Know For Certain

Descartes started with systematic doubt, i.e., he began with the view that everything was doubtable to see if there was anything that cannot be doubted. This resulted in the first principle of philosophy, "I think, therefore I am." The mind, or soul, or spirit is a thinking substance. It is certain that I exist, and I am a mind or thinking substance. This thinking provides Descartes' first metaphysical conclusion: There is mind.

The Deduction of God

Descartes provides two arguments (proofs) for Gods existence. The Eidological argument for God is that God must exist in order to account for our idea of perfection. Using a mixed syllogism, "If I have an idea of perfection, then there must actually exist a perfect being as its cause. I have an idea of perfection. Therefore, there must actually exist a perfect being." It is a causal argument for God, i.e., that an idea is a thing that needs a cause. The Ontological argument for God is that God must exist, otherwise he would not be the greatest being possible. Could God be the absolutely perfect being if he did not even exist? This reasoning provides Descartes' second metaphysical conclusion: There is a God.

The Deduction of Matter

Descartes viewed God as the guarantor of clear and distinct ideas. If there were no God it is possible to doubt the existence of the world and any of the other things that exist. But Descartes believed that God is incapable of creating in us false or misleading ideas. Errors in judgment occur, but only because of a misuse of our will that is given by God. This followed from the belief that God is supremely perfect and cannot be the cause of an error. Thus God is the guarantor of our knowledge. Using our sense perceptions granted by God we know that in the external world there must be a substance that supports the various physical qualities that we experience, i.e., a material substance. This substance must be extended, or occupy space and possess dimensions. This thinking provides Descartes' third metaphysical conclusion: There is matter.

Some Objections

Many philosophers have indicated that only sense experience is the source of knowledge (outside-in), rather than Descartes' view that knowledge comes through reason (inside-out). Another problem with Descartes' theory of reality is that he appears to have committed the fallacy of circular reasoning. Descartes accepts any clear idea as one that cannot be doubted, uses such ideas in his arguments for God's existence, but then insists that God ensures the reliability of the ideas. In addition, it is not clear why we could not have an idea of God without the existence of God.

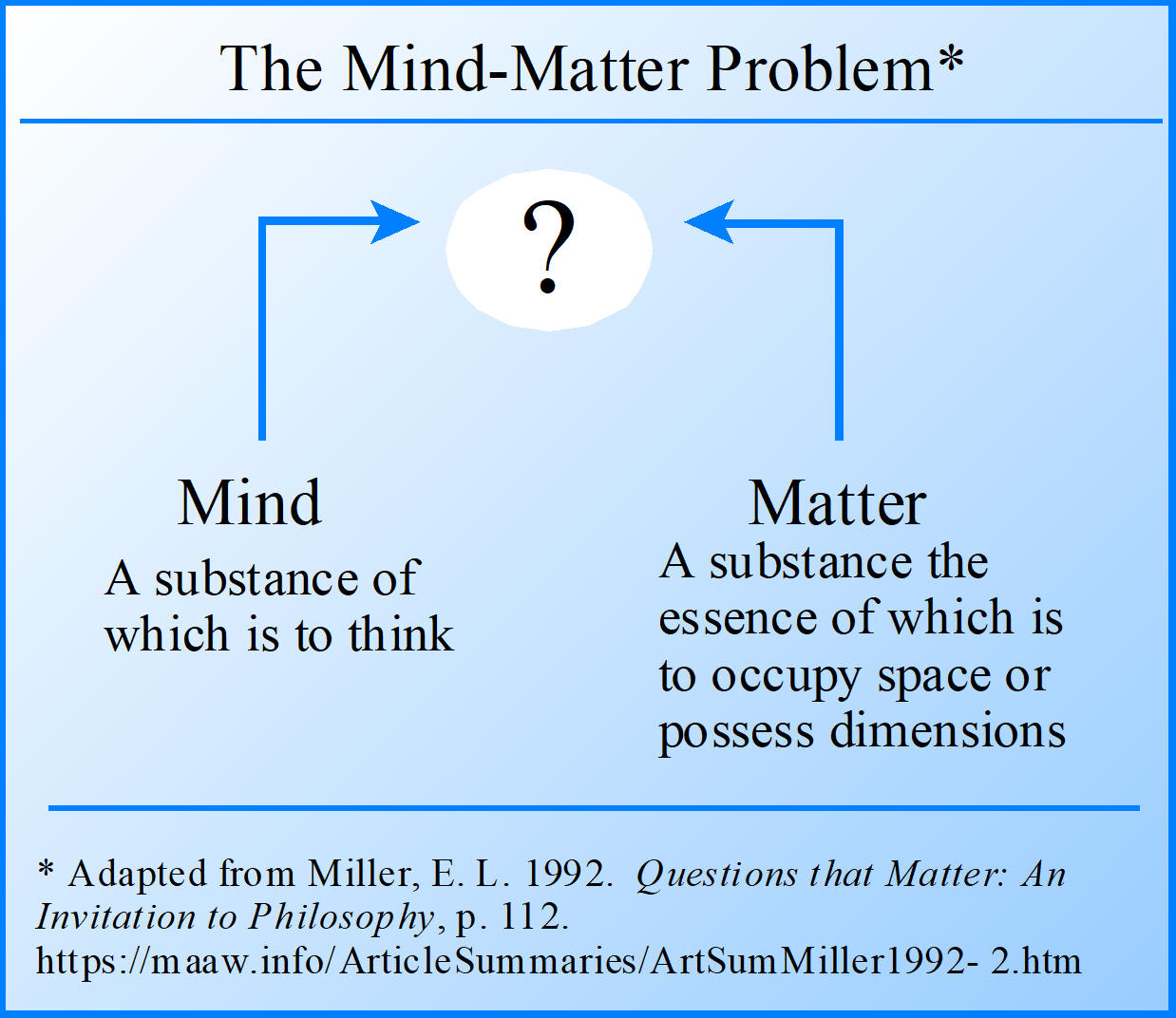

The Mind-Body Problem

Focusing only on the natural world, Descartes' theory is dualistic, i.e., mind and matter. The problem is how do we connect mind and matter if they are essentially two different substances? The mental effects of caffeine, drugs, and old age support the view that the mind and body are in a causal relation to each other, but how?

The mind-body problem is more difficult. In the book Minds, Brains and Science (1984) John Searle suggests that there are four aspects of the mind that appear unconnectable with the material world: consciousness, intentionality, subjectivity, and causation. How can physical systems have consciousness? How can a person's brain be about or refer to anything? How is it that we can feel pain? How can our thoughts cause a physical action?

Descartes proposed a solution to the causal problem called interactionism, i.e., there is an interaction between the mind and body that takes place in the pineal gland in the center of the brain. He did not explain how the mind and body interact, only where they supposedly interacted. Other proposed solutions include Malegranche's (1638-1715) occasionalism (on the occasion of bodily stimuli, God creates an appropriate response in the mind), Leibniz (1646-1716) pre-established harmony (body and physical states are preordained by God for every mental state), and Spinoza's double-aspect theory (there is only one reality known to us through its attributes of mind and matter). A more radical solution is addressed in the next two chapters, i.e., Idealism in Chapter 6 and Materialism in Chapter 7.

Mind: A Set of Dispositions or Functions

In the book The Concept of Mind (1949) analytic philosopher Gilbert Ryle said that the mind-body problem is not a real problem, but instead a pseudo problem resulting from a misunderstanding and misuse of language and concepts. The official doctrine that comes from Descartes is that every human has a body and a mind, but after death of the body a person's mind may continue to exist and function. Bodies are in space and can be inspected by external observers. But minds are not in space and are not witnessable by other observers. What happens to the body is public. What happens in the mind is private. According to Ryle, the official doctrine involves a category mistake, i.e., treating a concept as if it belonged to one category when it belongs to another. The mind is not some non-physical blob. A more useful idea is that the mind is a set of dispositions, e.g., thoughts, desires, convictions, moods, and inclinations evident in what people do.

Functionalism provides another view on the mind-body problem. This is the idea that the mind and its various states can be understood in terms of function. When addressing the significance of mental states it is not what they are made of that is relevant, but what they do. The mind-matter problem leads to a very interesting question that is addressed in Chapter 7. Are our minds and our brains the same thing?

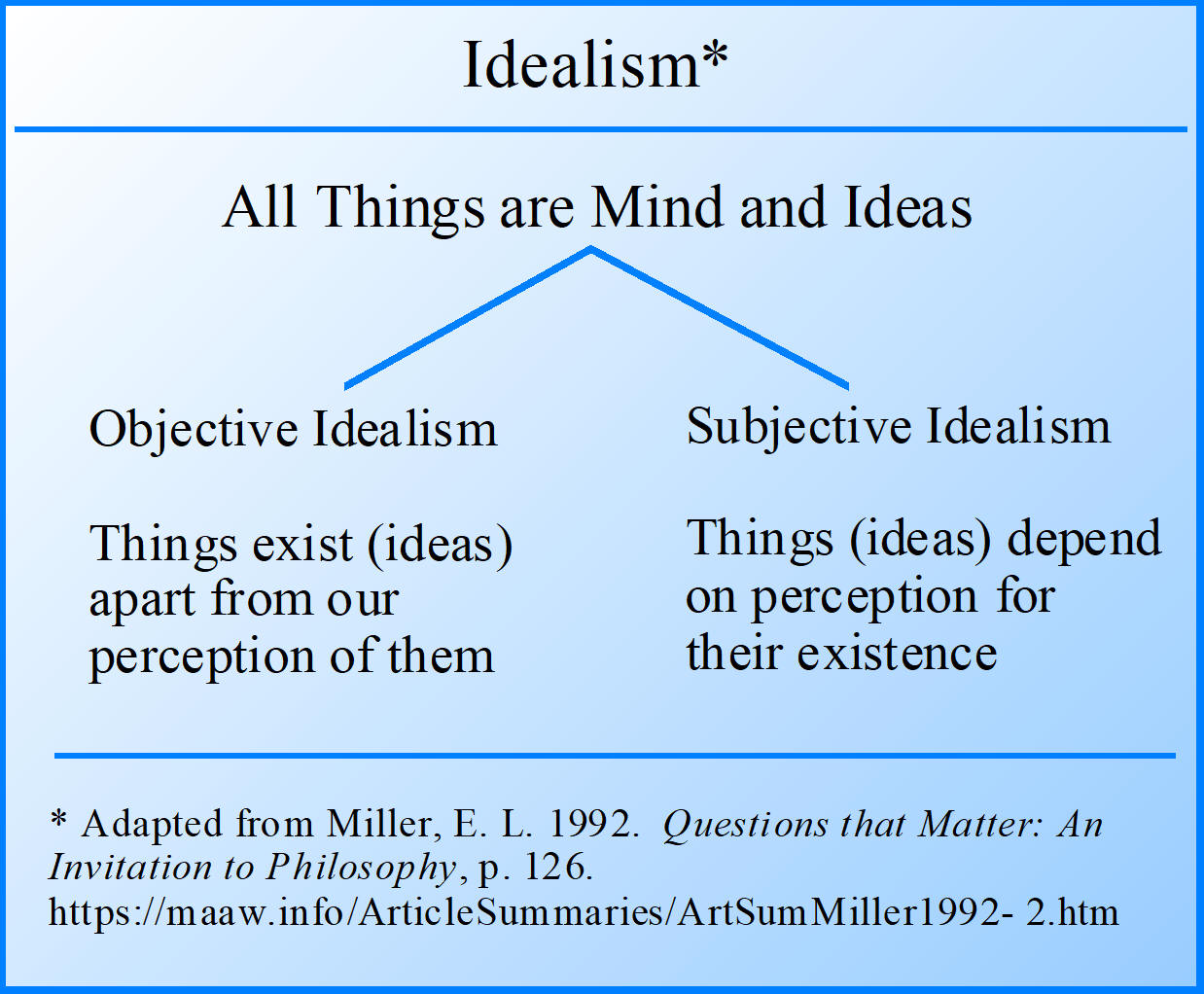

Idealism is the metaphysical monist theory that all things are constituted by mind and its ideas. It is a theory of reality that mind is ultimate and that all things are reducible to mind and ideas, i.e., "idea-ism." Two variants of idealism include:

Objective idealists - all things are made out of mind and ideas, but things exist out there independently of our perceiving or knowing them.

Subjective idealist - all things are made out of mind and ideas, and have no existence apart from our perception of them.

The most influential subjective idealist was Bishop George Berkeley (1685-1753). Berkeley's theory of reality grew out of John Locke's philosophy that included three features:

1. There are two substances, mind and matter (mind-matter dualist like Descartes).

2. Two main things are involved in the act of knowing, the knower and the known, but what is known are ideas about things.

3. Matter has two types of qualities: primary qualities (those that exist independently of a perceiver), and secondary qualities (those that depend on a perceiver). Primary qualities are objective, while secondary qualities are subjective (colors, sound, texture, taste). Secondary qualities vary with the perceiver and are relative. If there is no perceiver, there is no perception.

Berkeley's View: Esse Est Percipi - To Be is to Be Perceived

Berkeley believed that everything depends on perception for its existence. Everything ceases to exist in the absence of a perceiver. Berkeley's valid argument for this view is:

"Ideas exist only in minds

All things are ideas

Therefore, all things exist only in minds"

If the premises are true, the conclusion must be true. The second premise presented a problem.

Five Proofs for Subjective Idealism

1. The discontinuity of dualism - There is only reality, the mind and its ideas.

2. Matter as a meaningless idea - Matter is devoid of qualities and it is only by means of the qualities of something that we have an idea of it. To be is to be perceived.

3. The unexperienced as inconceivable - Anything cannot be conceived except as experienced. The idea is that as soon as you think of something you are experiencing it.

4. The inseparability of primary and secondary qualities - Primary qualities cannot be conceived except as inseparably bound up with secondary qualities. As a result primary qualities too must be subjective.

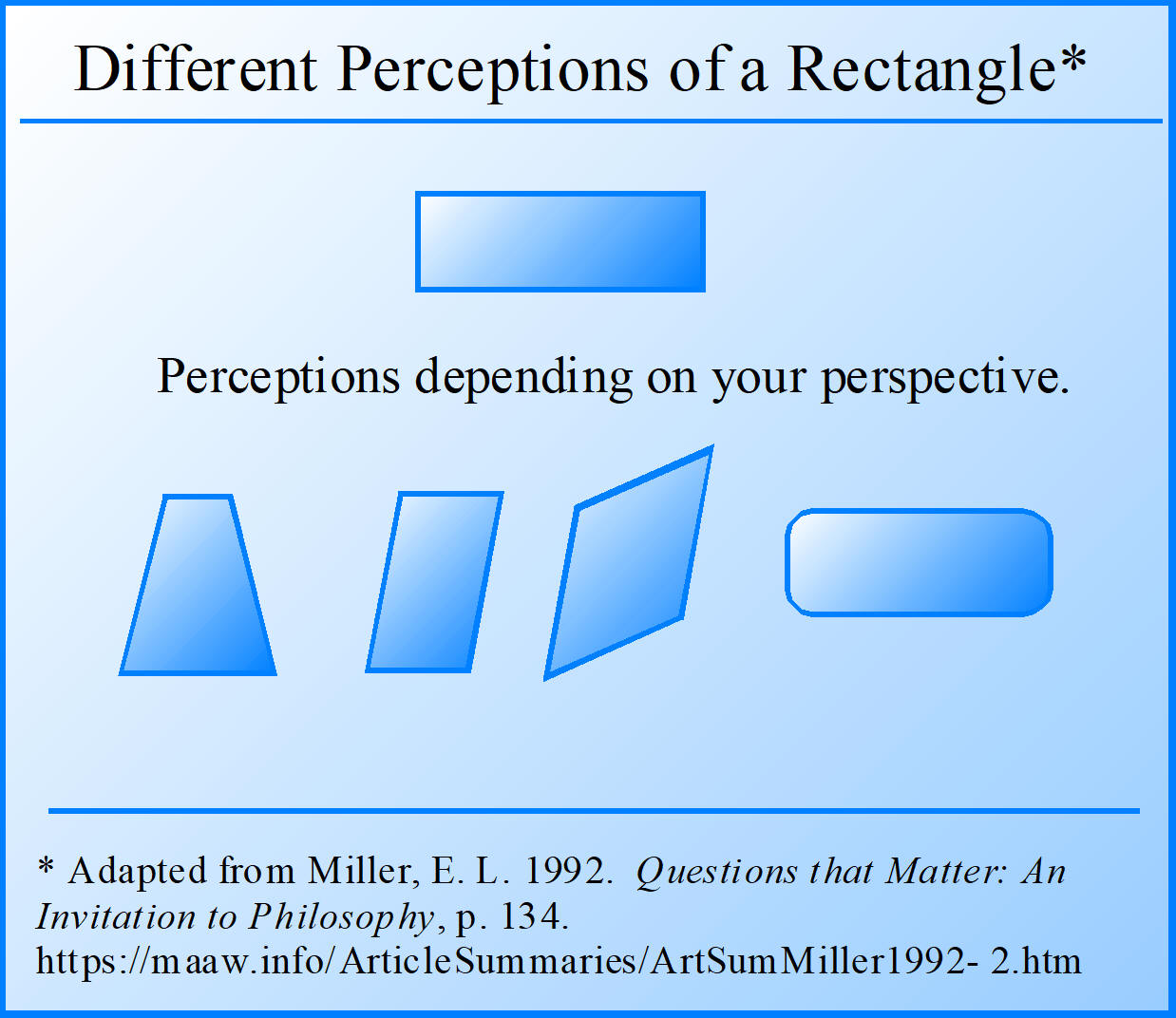

5. The relativity of all qualities - Primary qualities considered in themselves must be subjective. Secondary qualities such as colors, tastes, and sounds are relative to perceivers, or exist in the minds of perceivers. But qualities like shape, size, and motion are also perceived differently by people with different perspectives. For example, from different perspectives, a rectangle might be perceived as illustrated in the graphic below.

Size, position, and motion are also relative to the perceiver and therefore are perceptions or ideas.

Hylas and Philonous

In three dialogues Hylas argues for the reality of material substance, and Philonous represents Berkeley's position that everything depends on perception for its existence. These discussions (about five pages) lead to Berkeley's idea that a table is just what is perceived, a bundle of different perceptions or ideas.

Solipsism or God?

Solipsism is the belief that only one thing exist, the solipisist himself. Everything else exist only in his mind. Does this mean that Berkeley was a solipsist? No, Berkeley acknowledged the passivity of perception, i.e., the reality of things outside the mind. Although it seems inconsistent to claim that all things are ideas existing in our minds, and that they continue to exist even when unperceived by us, Berkeley argues that God, as an infinite Mind perceives all things. For Berkeley this served two purposes: there is no inconsistency in his subjective view of idealism, and it proves that God exist. His proof of God is as follows:

"The sensible world exists if, and only if, it is perceived by a mind;

The sensible world exist unperceived by human minds;

Therefore, the sensible world must be perceived by an infinite mind."

Some Objections

1. We can conceive of many things we cannot experience.

2. Berkeley denied the reality of material substance, but affirmed the reality of mental substance.

3. As with Descartes idea of mental substance, is it meaningful to view the mind as a sort of blob of something? A category mistake.

4. Matter is the essential stuff of all things. Chapter 7.

Materialism is a form of naturalism that repudiates any supernatural or spiritual reality, and uses observation, experimentation, and skepticism, rather than faith, dogma, intuition, and authority. Naturalist are tough-minded philosophers who consider only those things that can be investigated as things that exist. Naturalism includes two views:

The Wider View - Nature includes matter as one of many dimensions of nature.

The Narrow View - Nature is the physical world, i.e., only matter.

What is Materialism?

Materialism represents the narrow view of naturalism and is defined as the metaphysical doctrine that matter with its motions and qualities is the ultimate reality of all things, i.e., everything in the universe is reducible to matter, to physical states, and to a position in space and time.

Materialism denies the reality of mind, or reduces it to matter. This idea can be traced back to Socrates who taught that all things are made up of indivisible particles or atoms. Epicurus (a Greek philosopher around 300 B.C.) adopted the idea and concluded that upon death the soul disperses so that life after death was not possible.

Man A Machine

Mechanistic materialism is an extreme form of materialism, or a theory of reality where not only are all things reducible to matter and motion and located in space and time, but all things happen with particular features according to a finite number of fixed laws. Everything is a machine. This thinking was influenced by Descartes' view of the world as ordered by fixed laws, and Isaac Newton's three laws of motion:

1. A body remains at rest or in motion with a constant velocity unless acted on by an outside force.

2. The sum of the forces acting on a body is equal to the product of its mass and acceleration.

3. For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction.

Mechanistic materialism goes further and includes the view that everything is caused in such a way that it could not have been otherwise. All things are predetermined by unalterable mechanistic laws. The implication is that man is also a machine. This was the theme of the French physician La Mettrie's 1748 publication Man a Machine where he argued that thoughts, sensations, and emotions are all a matter of organs, nerves, impulses, reflex movements, and blood flow.

The New Materialism

In 1963 the Australian philosopher J. J. C. Smart rejected causal determinism and described a purely physicalistic theory of mind referred to as the Identity Thesis. This is the view that the mind, including thoughts, perceptions, and emotions are identical with brain states such as nerve cells and electrical impulses.

Are The Mind and Body Identical?

Some have objected to the identity thesis (that mind and brain are identical) on the grounds that mental states and brain states are different. The American philosopher Richard Taylor raised questions such as: "I can be blamed, but can my body be blamed?" "My thoughts can be true or false, but can my brain be true or false?" From the functionalist point of view, a one-to-one relation between brain states and mental states need not hold. Their view is that there is no single type of physical state that always corresponds to a certain mental state. Therefore, the mind and the brain must be different.

Beyond Freedom and Dignity: Skinner

Behaviorist B. F. Skinner (1904-1990) provides the best recent example of both a physicalistic view of mind and pervasive causal determinism. Soft behaviorism considers observable human behavior as the appropriate object of psychological study. Hard behaviorism, on the other hand is a materialistic and mechanistic view that considers observable behavior as all there is.

In Beyond Freedom and Dignity (1972) Skinner argues that almost all of our major problems involve human behavior, and that these problems cannot be solved with physical and biological technology alone. What is needed is a technology of behavior, i.e., a manipulation of human behavior and transformation of values in accordance with the progress of ideals of the evolutionary process. Skinner viewed human values as dependent on social contingencies and conditions where each culture has its own views on what is good. What is considered good in one culture may not be considered good in another culture. Values aren't universal and objective, they are a by product of the environment and social conditions. Skinner tells us that the idea of autonomous man (free will and self-controlling) has been constructed from our ignorance. This should be rejected and replaced with a technology of human nature along the lines of hard behaviorism. All things are reducible to physical states, and all things are causally determined. "The problem is to induce people not to be good but to behave well."

Are All Things Determined?

One problem with mechanistic materialism is not that everything has a cause, but that everything is causally determined, i.e., could not have happened otherwise. This means the denial of free will. How could moral responsibility and authentic thinking exist without free will? Many philosophers also have a problem with the identity thesis (i.e. the mind and brain are identical) because it denies human existence beyond space and time (transcendence), or simply that life after death is not possible.

_____________________________

Go to the next Chapter: Chapter 8: Skepticism

Related summaries:

Dawkins, R. 2008. The God Delusion. A Mariner Book, Houghton Mifflin Company. (Summary).

Martin, M. and K. Augustine. 2015. The Myth of an Afterlife: The Case against Life After Death. Rowland & Littlefield Publishers. (Notes and Contents).