The Question of Society: Summary of Chapters 20-22

Study Guide by James R. Martin, Ph.D., CMA

Professor Emeritus, University of South Florida

Chapters 1-2 |

Chapters 3-7 |

Chapters 8-11 |

Chapters 12-15 |

Chapters 16-19

Introduction to Part Five

Moral values and social and political values are closely related. Consider issues related to fairness, justice, freedom, and rights, e.g., civil disobedience, welfare, women's rights, racial discrimination, pornography, and abortion. These are clearly both ethical and social-political issues. The social-political philosopher is concerned with questions of value related to the public good, how it should be implemented, and the basis for human rights and justice.

Chapter 20: Some Historical Background

This chapter examines some of the ideas from the ancient and medieval periods (particularly the case of natural law) to set the stage for subsequent developments.

Plato: The Elitist

Plato examined a number of social-political perspectives and advocated aristocracy or elitism (rule by a select few) as an acceptable form of government. Plato's Republic was a book about social and political issues including ethics, metaphysics, epistemology, and art. Plato considered five political theories including: timocracy, oligarchy or plutocracy, democracy, despotism or dictatorship, and aristocracy.

1. Timocracy - Plato defined timocracy as rule by those who are primarily motivated by ambition and honor. He rejected this idea because such rulers are dominated by the emotional or inferior part of the soul.

2. Oligarchy or plutocracy - Rule by the rich. He rejected oligarchy or plutocracy because it would inevitably cause alienation and class warfare between "the haves" and "the have-nots."

3. Democracy - Plato viewed democracy as the actual and equal participation of every citizen in the affairs of the state rather than participation by representation. Plato rejected democracy because he believed that majority rule would result in mob rule.

4. Despotism, or dictatorship - Absolute rule of a single individual. Plato rejected this form of government because he believed in Lord Acton's famous saying, "All power corrupts; absolute power corrupts absolutely."

5. Aristocracy or elitism - Rule by the best. Plato believed philosophers were the best qualified to rule.

Plato considered philosophers as those who can apprehend the eternal and unchanging. Philosophers should be chosen whose knowledge is perhaps their greatest point of superiority, provided they do not lack other qualifications. These include a passion for knowledge and a desire to know the whole of reality. They should possess a love of truth and a hatred of falsehood, and not tolerate untruth in any form. They should also be temperate and free from the love of money, meanness, pretentiousness, and cowardice. They require a good memory, measure and grace, and will be instinctively drawn to every reality in its true light. They must be quick to learn and to remember, magnanimous and gracious, the friend of truth, justice, courage, and temperance.

Although Plato was an early advocate of women's rights, he also proposed a program of eugenics, censorship, arranged marriages, and community of property and children.

Aristotle: The Democrat

In Politics Aristotle indicated that the state was the most encompassing of human institutions. He rejected Plato's aristocracy or elitism and the extreme form of democracy (mob rule), but he did believe that an adequate form of government should accommodate the rank and file of the citizenry. "The principle that the multitude ought to be supreme rather than the few best is one that is maintained, and, though not free from difficulty, yet seems to contain an element of truth."

Is There a Natural Law?

In Ethics Aristotle distinguished between conventional laws established by general agreement, and natural law or law derived directly from the natural order of the world including the built-in tendencies of human nature. Natural law is defined as general and universal rules of conduct, both personal and social, derived rationally from nature. According to Aristotle, they are discoverable in the very nature of things.

St. Thomas accepted much of Aristotle's philosophy and transformed it from a Christian perspective. This included four kinds of law:

1. Eternal law - governance of all things by the divine reason.

2. Natural law - eternal law revealed specifically in human nature and known by human reason.

3. Human law - specific statutes and legislation contrived by humans to apply nature law to practical situations.

4. Divine law - direction for humanity's supernatural end, known only through divine grace rather than through reason.

Only natural law and human law are related to social and political issues. The key to any doctrine of natural law is a general view of reality that social and political values are built into the world and human nature, and that they can be rationally discovered, expressed and applied. Those who accept the idea of a natural law believe that there is a rhyme and reason to things, and that values have an objective foundation.

Chapter 21: Liberalism vs. Marxism

Our social-political system is mainly determined by the debate between liberalism and Marxism, or the economic expressions, capitalism and communism. To be informed about the social-political realities that continue to confront us, we need to grasp these competing perspectives.

The Liberal Perspective: Locke

In the context used in this chapter the word liberalism refers to classical liberalism, or a general social-political theory that underlies our entire social-political system, including both liberals and conservatives. Liberalism comes from the Latin libertas, liberty or freedom. Classical liberalism insists on freedom for the pursuit of individual interests, and freedom from undue external, and government controls. Many freedoms appear in the first ten amendments to the Constitution of the United States. For example, freedom of religion, freedom of speech, and freedom to peaceably assemble appear in Amendment I. With regard to a well regulated Militia, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed appears in Amendment II. Classical liberalism may also be referred to as individualism since the state is viewed as the servant of the individual, and the guarantor of the individual's interest and rights.

John Locke (1632-1704) was the primary advocate of the classical liberal perspective. Locke believed that all private and public good is based on natural law that displays fundamental rights and liberties. For Locke, God is the objective source of natural law, and natural law can be discovered rationally. Locke challenged the prevailing view that monarchs were established by God, and that all others were subservient to them. He instead believed that the natural state is governed by natural law, and natural law legislates freedom, equality, and inherent rights for all. However, a social contract is needed where members of society agree to forfeit certain rights and privileges in order to preserve others. The social contract is something that evolves as members of the system give tacit consent to support the contract. When people unite into a community, they must give up power to the majority of the community. Any political society is nothing but the consent of any number of free men capable of a majority to unite and incorporate into such a society. And that is the beginning of any lawful government in the world. The main purpose of free men uniting and giving up the equality, liberty, and executive power they had in the state of nature is to preserve their property. But the power of society can never be supposed to extend farther than the common good. The Declaration of Independence reflects Locke's ideas of natural law, social contract, and individual rights.

Liberalism and Capitalism

Classical liberalism includes the economic freedom of the individual alone, or with others to own the means of production and to produce and sell goods for a profit. This is the basis of capitalism. Locke regarded the individual's right to own property as the most important of natural rights and the preservation of their property is the reason why men unite into common-wealths putting themselves under government.

In his Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776) Adam Smith (1723-1790) provided a more specific expression to the rights of the individual in a free market system of capitalism. Smith used the French term laissez faire ("let it alone" or "hands off") to describe the concept of individual economic freedom, and he believed that it would provide the best economic approach for everyone. The mechanisms of supply-and-demand and free enterprise provide an efficient arrangement for all concerned, owner, merchant, worker, and consumer. Although every individual intends only his own gain, an "invisible hand" will promote the interest and good of a capitalist society.

Both liberals and conservatives embrace the idea of classical liberalism, i.e., individual rights, and the social responsibility of the state. However, conservatives defend individual freedom from encroachment by the state, while liberals emphasize the state responsibility to ensure individual rights. The real attack on classical liberalism is the radical alternative of Marxism.

A Radical Response: Marx

The work of G. W. F. Hegel (1770-1831) provides the roots of Marxism. Hegel was an objective idealist who believed that reality is "idea-listic" or spiritual in nature, and exist objectively or independently. Reality is a spiritual process that is always changing by a mechanism he referred to as dialectic, a give-and-take between opposite states. The process is represented as a synthesis of opposite states, thesis and antithesis. Karl Marx (1818-1883) used the idea of the historical dialectic and gave it a materialistic twist referred to as dialectical materialism. This is the metaphysical view that reality is matter and motion, and evolves historically in accordance with the dialectical principle of synthesis of opposite states. Marx used it to promote class warfare as a social and economic expression of the historical dialectic to achieve a classless society where private ownership of the means of production would be abolished, and wealth would be equitably distributed, i.e., communism. At the time Marx began developing the communist philosophy, the working class (proletariat) labored in squalid working conditions, and received a wage wholly determined by the owning class (bourgeoisie). The capitalist industrial system included child labor and the workers were alienated from the products they produced, from themselves, from their human nature, and from their fellow workers. Marxism lead to the communist revolution (led by Lenin) in Russia in 1917, the revolutions in China (Mao Tse-Tung) and Cuba (Castro), and to labor unions and socialist programs in many other countries.

Some Objections

Some have argued that Marxists have not recognized that other social systems are capable of introducing important social changes, and that capitalism has proved that it can be self-correcting through its own dialectic of improvement. In addition, Marxism is naive and over-optimistic in its view of human nature. The very repression of human values that Marxists condemn in other government systems reveals itself even more vividly in communist systems.

Is Prosperity a Deception? Hospers vs. Marcuse

Although there are variations of libertarianism, most libertarians would subscribe to three ideas.

1. The freedom of individuals to pursue their private interests as long as they do not harm others,

2. The denial of the state's responsibility for all forms of public welfare, and

3. A "night-watchman" conception of government where the government exist solely for the protection from enemy invasion, to prevent infringement on individual rights, and to enforce contracts, etc.

Libertarianism takes laissez faire to a different level, relegating government to a role purely subservient to individual interest as opposed to the interest of society. In Free Enterprise as the Embodiment of Justice (1978) libertarian John Hospers compares the economic successes of the free enterprise system (capitalism, freedom, and affluence) with the failures of the communist system (tyranny, regulation, and misery). He argues that by 1825 capitalism had created in the United States the most prosperous nation in the history of the world. Other countries that have embraced the free enterprise system have prospered as well including West Germany, Malaysia, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Japan, while East Germany, India, China, Vietnam, and Cambodia who rely on central planning are heavy with the dead weight of bureaucracy.

In One-Dimensional Man Marxist Herbert Marcuse argued that modern capitalist societies have deceived their citizens and have substituted one form of alienation for another. A higher standard of living is illusory. The capitalist system strains and drains itself economically and psychologically in pursuit of military prowess and possible war, "the peaceful production of the means of destruction." The threat of an atomic catastrophe serves to protect the very forces that perpetuate this danger. The whole appears to be the embodiment of reason, but the defense structure is destructive of the free development of human needs, and society is irrational as a whole. The high standard of living in the capitalist system is a cruel deception because the citizens are blinded to the trivializing and dehumanizing price that must be paid for the good life.

Chapter 22: The Question of Justice

The idea of justice is the most basic idea of social and political philosophy. Does justice involve equity and fairness? If so, how should equity and fairness be defined? Does it involve worthiness? If so, what is the basis for worthiness? Does it involve social responsibility? Then how is social responsibility to be measured?

The Problem

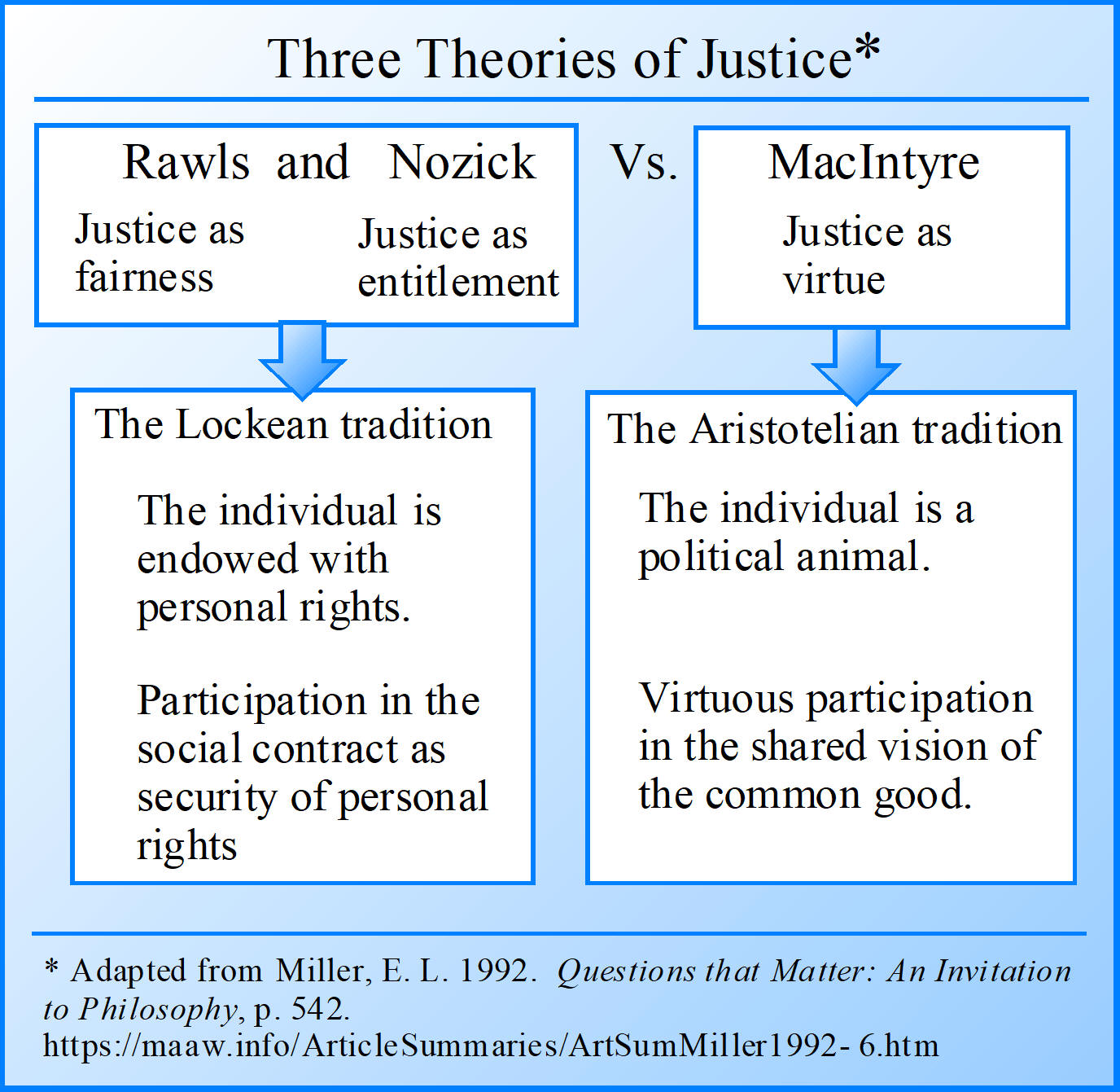

The purpose of this chaper is to focus on a few recent contributions related to the question of justice. In After Virtue: A Study of Moral Theory (1981) Alasdair MacIntyre explained the problem using two hypothetical individuals A and B. Individual A may be a store owner, a police officer, or a construction worker who believes he has a right to keep what he has earned and regards rising taxes as unjust. Individual B may be a social worker, or someone with wealth who is impressed by the inequalities in the distribution of wealth, income and opportunity. He is also impressed by the inability of the poor and the deprived to do much about their condition because of the inequality in the distribution of power. He believes both of these inequalities are unjust and that redistributive taxation to finance welfare is what justice demands. In both cases the price for one person or group of people receiving justice is always paid by someone else. Neither principle is socially or politically neutral. John Rawls argues in favor of B's position, and Robert Nozick argues in favor of A's position.

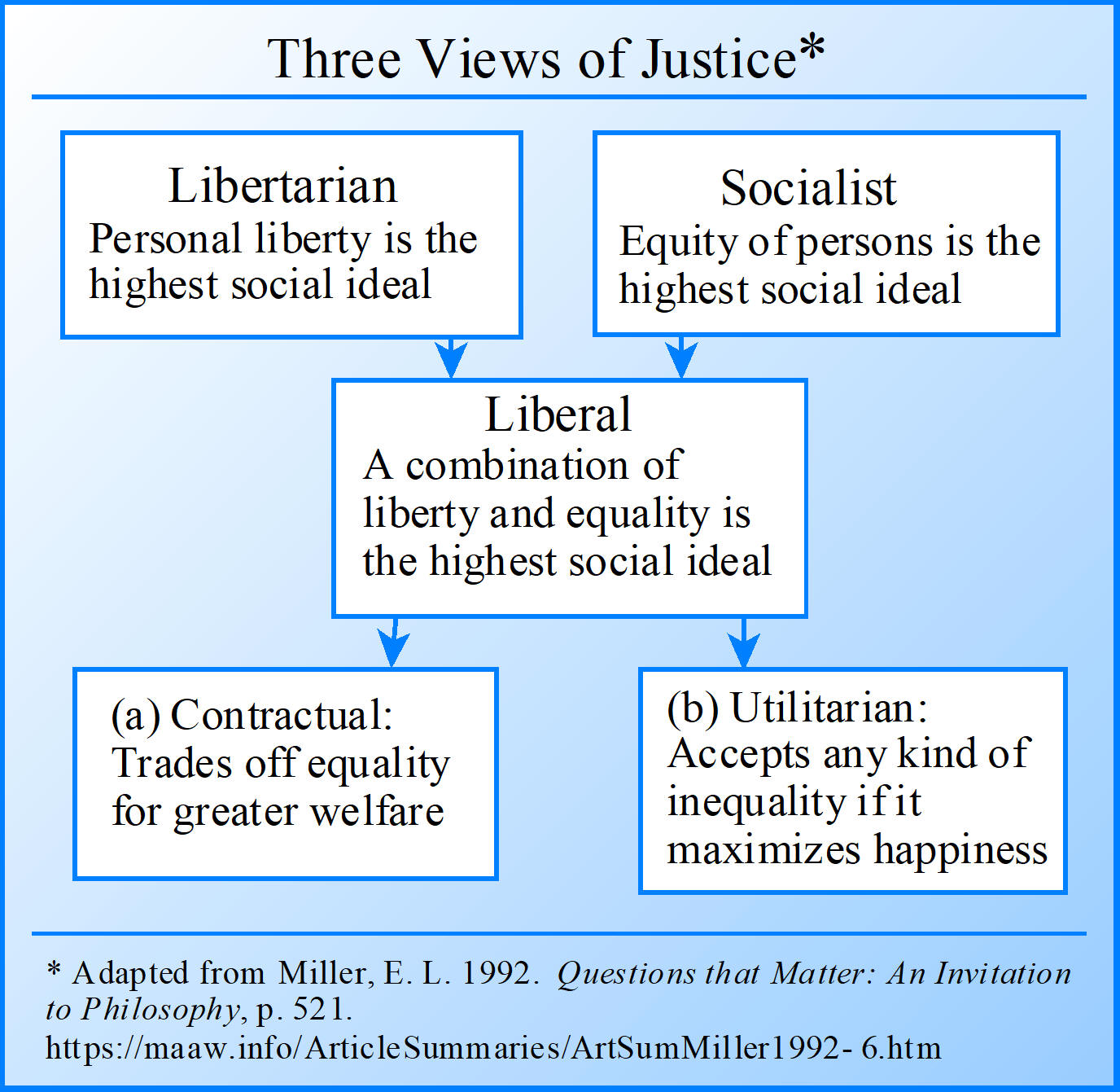

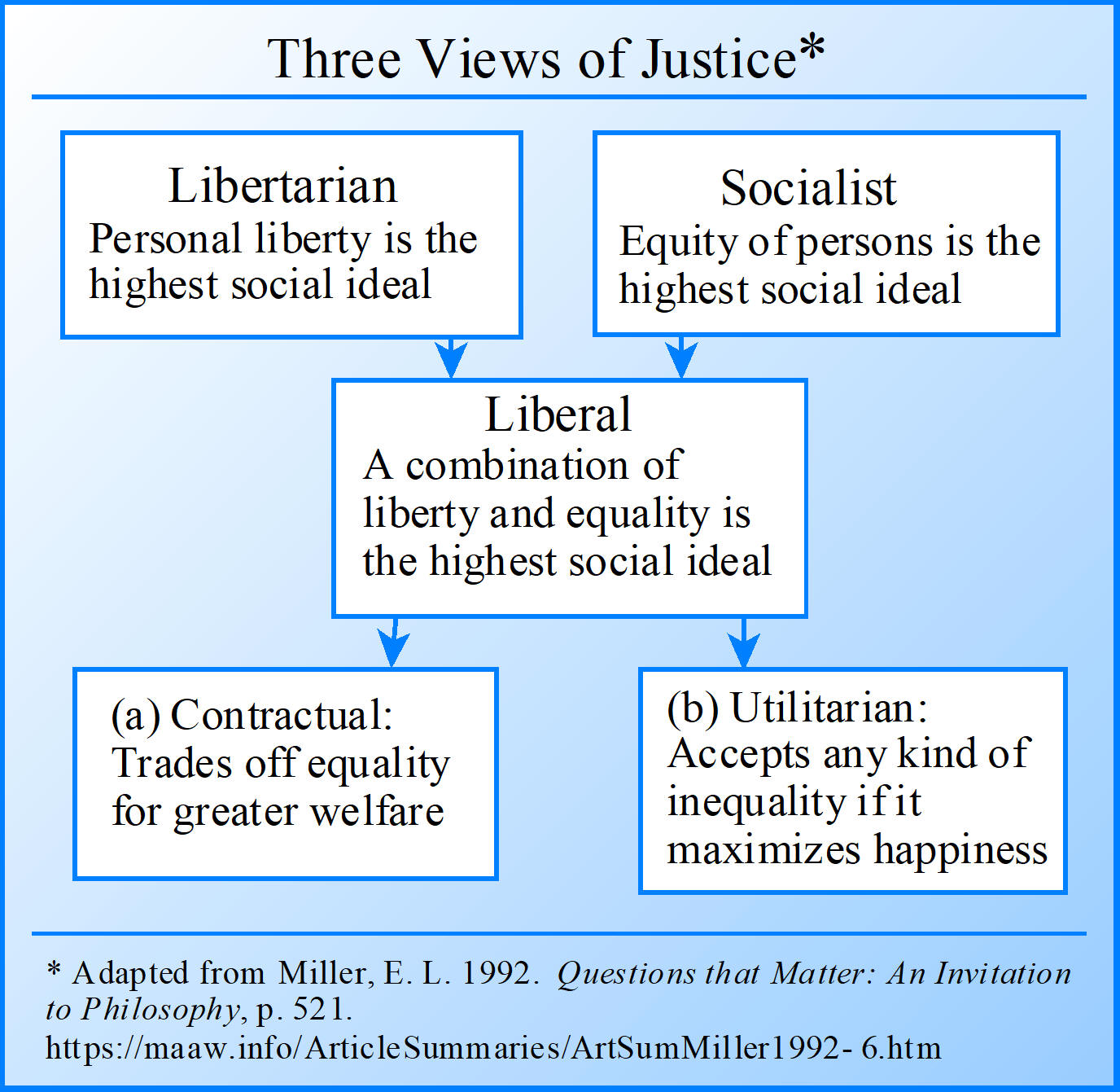

Rawls: Justice As Fairness

In his books Justice as Fairness and A Theory of Justice John Rawls attemps to combine the libertarian view of justice (personal liberty) with the socialist view of justice (social equality) to obtain the liberal view of justice (a combination of liberty and equality). The liberal view of justice has two forms: (a) contractual and (b) utilitarian. The contractual form involves an agreement between persons who willingly limit their freedoms in exchange for greater equality. The Utilitarian form involves the adoption of rules that would promote the maximization of happiness.

Rawls begins with the idea of an original hypothetical position where there is no prejudice in favor of one principle rather than another (a veil of ignorance). Then, assuming the social-contractors are rational, they will be impartial and favor a principle that results in a fair share for all. This leads to two principles:

1. The Principle of Equal Basic Liberty for All - Each person is to have an equal right to the most extensive basic liberty compatible with a similar liberty for others.

2. The Difference Principle - Social and economic inequalities are to be arranged so that they are both reasonably expected to be to everyone's advantage, and attached to positions and offices open to all. For example, it is to everyone's advantage that medical doctors earn more than others if we receive better healthcare as a result.

A more general conception of justice is that all social values (liberty and opportunity, income and wealth, and the bases of self-respect) are to be distributed equally unless an unequal distribution of any, or all, of these is to everyone's advantage. Inequalities are unjust if they are not to the benefit of all. This is a principle of equality with respect to needs.

Critics argue that Rawls theory is very abtract and hypothetical when compared to real life situations and the implementation of his theory needs a deeper moral principle. According to William R. Marty, Rawl's distribution of the pie is faulty because it divorces distribution from a number of things that can legitimately provide a claim to a particular share of a distribution, e.g., contribution, risk, need, skill, responsibility, and performance. These are things one needs to know to distribute justly. The Rawlsian method assumes that an equal division is a fair division, but it can and does defend unjust divisions and as a result fails as a means of locating justice.

Nozick: Justice as Entitlement

In Anarchy, State, and Utopia (1974) Robert Nozick argues for a principle of equality with respect to entitlement, rather than Rawl's principle of equality with respect to needs. There are two main features of his theory: the minimal state, and his conception of justice as entitlement. The state should be limited to the narrow functions of protection against force, theft, fraud, and enforcement of contracts. The minimal state is only to protect the rights and properties of its citizens. The justification for this view is that individuals are endowed with certain inalienable rights. The entitlement theory is that people are entitled to the property they have acquired legitimately, and they are entitled to dispose of it any way the desire as long as this does not infringe on the rights of others. Nozick's theory includes three principles:

1. The Principle of Justice in Acquisition - An acquistion of something is just if the something is previously unowned and acquisition leaves enough to meet the needs of others.

2. The Principle of Justice in Transfer - A holding is just if it has been acquired through a legitimate transfer from someone who has acquired it through a legitimate transfer or through original acquisition.

3. The Principle of the Rectification of Justice in Holdings - An honest attempt must be made to identify the sources of illegitimate holdings and to compensate the victims.

The complete principle of distributive justice is that a distribution is just if everyone is entitled to the holdings they possess under the distribution. The controlling idea is entitlement rather than Rawls idea of fairness. Nonvoluntary redistribution of income or goods to achieve equality of material condition is impermissible because forcing some to contribute to the welfare of others violates the rights of those who are forced.

A frequent complaint against Nozick's theory is his emphais on natural rights. His appeal to self-evident principles is vulnerable because it does not include a sustained defense of this doctrine. Both Rawl's and Nozick's theories are said to offend our moral sensibilities.

MacIntyre: Justice as Virtue

In After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory (1981) Alasdair MacIntyre challenged the Rawlsian and Nozickian theories on the grounds that they both leave out something crucial, the idea of desert - how deserving a person is as the crucial component of justice. Individual interests are primary and the interest of society is secondary in both theories. But the notion of what one deserves is relevant only in the context of a community whose bond is a shared understanding of the good for man and the good of the community where individuals identify their primary interest. The absense of the idea of community accounts for the their failure to accomodate in their theories the notion of desert. People getting what they deserve only makes sense when we recognize that "we are all in this together."

MacIntyre intends to replace the previous theories with the tradition of virtues from Aristotle's theory of virtue. A virtue is a mean between vices (e.g., courage is a mean between foolhardiness and cowardice). Virtues play a role in social life as well as in the life of the individual. The social community is formed for the common good, and the virtues are conductive to the common good or well-being of the community. The application of the law to regulate behavior conducive to the common good requires the virtue of justice. This requires rewarding on the basis of desert in accordance with right reason. The emphasis is shifted from the individual to the larger community and the shared, common good that individual participants in the community contribute through their virtuous activity. MacIntyre's idea of justice is more wholistic than the theories based on individual needs or rights, i.e., communitarian rather than individualistic. Justice is the rewarding of the virtuous activity that enhancs the common good of man.

_______________________________

Related summaries:

Buchanan, M. 2002. Wealth happens. Harvard Business Review (April): 49-54. (Buchanan describes a universal law of wealth based on a network effect that appears to have some important implications for economic policy). (Note).

Martin, J. R. Not dated. A note on comparative economic systems and where our system should be headed. (Note).

Martin, J. R. Not dated. Chapter 1: Introduction to Managerial Accounting, Cost Accounting and Cost Management Systems. Management Accounting: Concepts, Techniques & Controversial Issues. Management And Accounting Web. This chaper includes a discussion of two very different variants of capitalism, i.e., individualist and communitarian. Chapter1.

Oser, J. 1963. The Evolution of Economic Thought. Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc. (Summary). See Chapter 5 for more on Adam Smith and Classical Economic Theory. See Chapters 9 and 10 for more on Socialism and Marxism.

Porter, M. E. and M. R. Kramer. 2011. Creating shared value: How to reinvent capitalism and unleash a wave of innovation and growth. Harvard Business Review (January/February): 62-77. (Summary).

Prothero, S. 2007. Religious Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know - And Doesn't. Harper San Francisco. (Summary).

Thurow, L. C. 1996. The Future of Capitalism: How Today's Economic Forces Shape Tomorrow's World. William Morrow and Company. (Summary).