The Question of Morality: Summary of Chapters 16-19

Study Guide by James R. Martin, Ph.D., CMA

Professor Emeritus, University of South Florida

Chapters 1-2 |

Chapters 3-7 |

Chapters 8-11 |

Chapters 12-15 |

Chapters 20-22

Introduction to Part Four

This section includes four chapters that examine ethical or moral values that define personal decisions and actions as good or evil, moral or immoral. Moral philosophy, or ethics is one aspect of value theory. It is concerned with the clarification of fundamental ethical concepts and the various critical positions and perspectives on ethical behavior and morality.

Chapter 16: Challenges to Morality

This chapter examines four main challenges to the moral absolutism argument examined in Chapter 13. Moral absolutism is also referred to as the objectivist or ethical absolutist view of morality, i.e., that moral values are independent of individual opinions, and instead are fixed and common to all. The four challenges include:

1. The Logical Positivist - who view ethical propositions as meaningless.

2. The Relativists or Subjectivists - who believe morality is a matter of individual (person, community, society, or culture) judgment, and there are no common universal moral obligations.

3. The Existentialist or Humanist - who argue that the basis of morality evolves with human nature.

4. The Determinist - who believe that all things are causally conditioned such that they could not be otherwise, and therefore there is no basis for moral responsibility, i.e., no free will.

The Challenge of Logical Positivism

Logical positivism maintains that the language of traditional morality is meaningless. An underlying concept of logical positivism is the verification principle, i.e., that a proposition is cognitively meaningful if and only if it is either analytic or in principle empirically verifiable. The implications of this principle are that all metaphysical claims (e.g., about God, souls, free will, causal relations) are cognitively meaningless. Moral propositions make no claims about reality, but are instead emotional expressions of one's likes or dislikes. This position on morality is referred to as emotivism. Critics argue that this view of morality does not work in practice.

The Challenge of Relativism

Ethical relativism or ethical subjectivism is the view that the individual (person, community, society, or culture) is the source of moral judgments. Moral claims are cognitively meaningful (true or false), but there are no common or universal or objective moral values. This idea was mentioned in Chapter 7 in reference to B. F. Skinner's Beyond Freedom and Dignity where Skinner stated that what is good in one culture may not be considered good in another culture. In Anthropology and the Abnormal (1934) anthropologists Ruth Benedict stated "We recognize that morality differs in every society, and is a convenient term for socially approved habits." The argument is essentially that ethical views and opinions are largely or even completely conditioned by our circumstances, e.g., where we were born, how we were raised, our education, religious instruction, skin color, and even height.

According to the author, relativism denies that any value or idea is any better than any other. However, this seems to conflict with Bertrand Russell's argument for the relativist position discussed in Chapter 13. Russell argued that conduct that is right is what would probably produce the greatest possible balance in intrinsic value of all acts possible in the circumstances. A person has to consider the probable effects of their action to determine what is right.

The Challenge of Existentialism

Existentialism is the philosophy that emphasizes the existing individual as the point of departure for philosophical questions. According to Jean-Paul Sartre (1844-1900) the idea that everything is what it is by virtue of transcendent essence is wrong. The main idea in existentialism is that existence precedes essence. The individual is alone. We are free and unconditioned by any moral law or eternal values. Human beings in their freedom are the basis of values. This is the humanistic view that humanity is at the center of determining value and meaning. Humanism is similar to relativism but different in that relativism denies any objective or common values, and views the individual, community, society, or culture as the source of subjective values. Humanism, on the other hand affirms objective values and locates the source as humanity rather than God.

The Challenge of Determinism

Determinism was defined in Chapter 7 as the view that all things are causally conditioned such that they could not be otherwise. If this is true, then morality is impossible. It is a denial of free will, and morality presupposes free will. Hard determinist believe all things are determined and are determined by external factors that we cannot control. Soft determinist believe that our choices cannot be otherwise, but that the causes (our desires, inclinations attitudes, etc.) are within the individual. Critics of this view (free-willists) argue that soft determinism reduces to hard determinism because it essentially denies moral responsibility.

This chapter considers the very old view of morality referred to as hedonism, and the question of whether the consequences of our actions matter morally.

The Question of Consequences

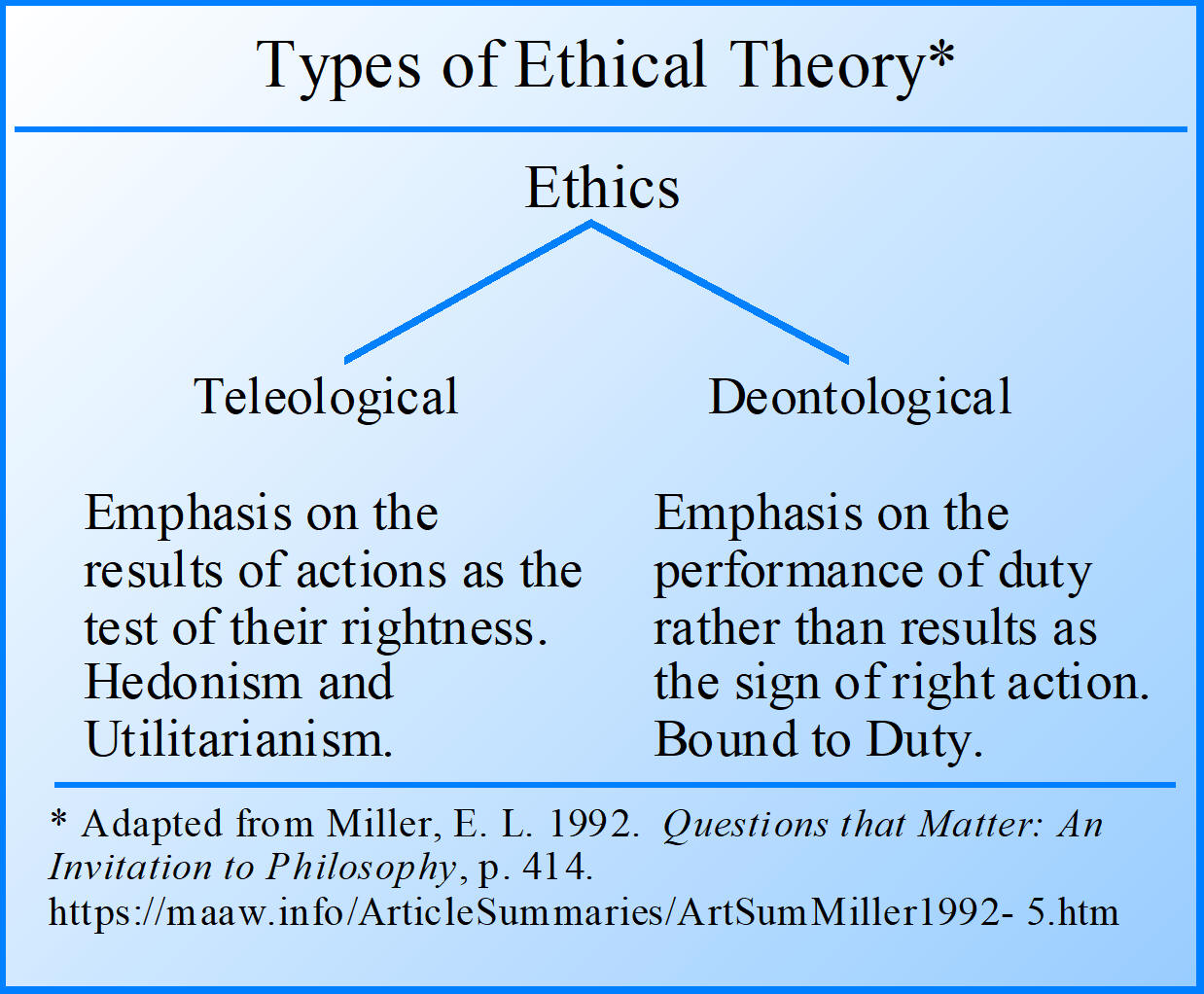

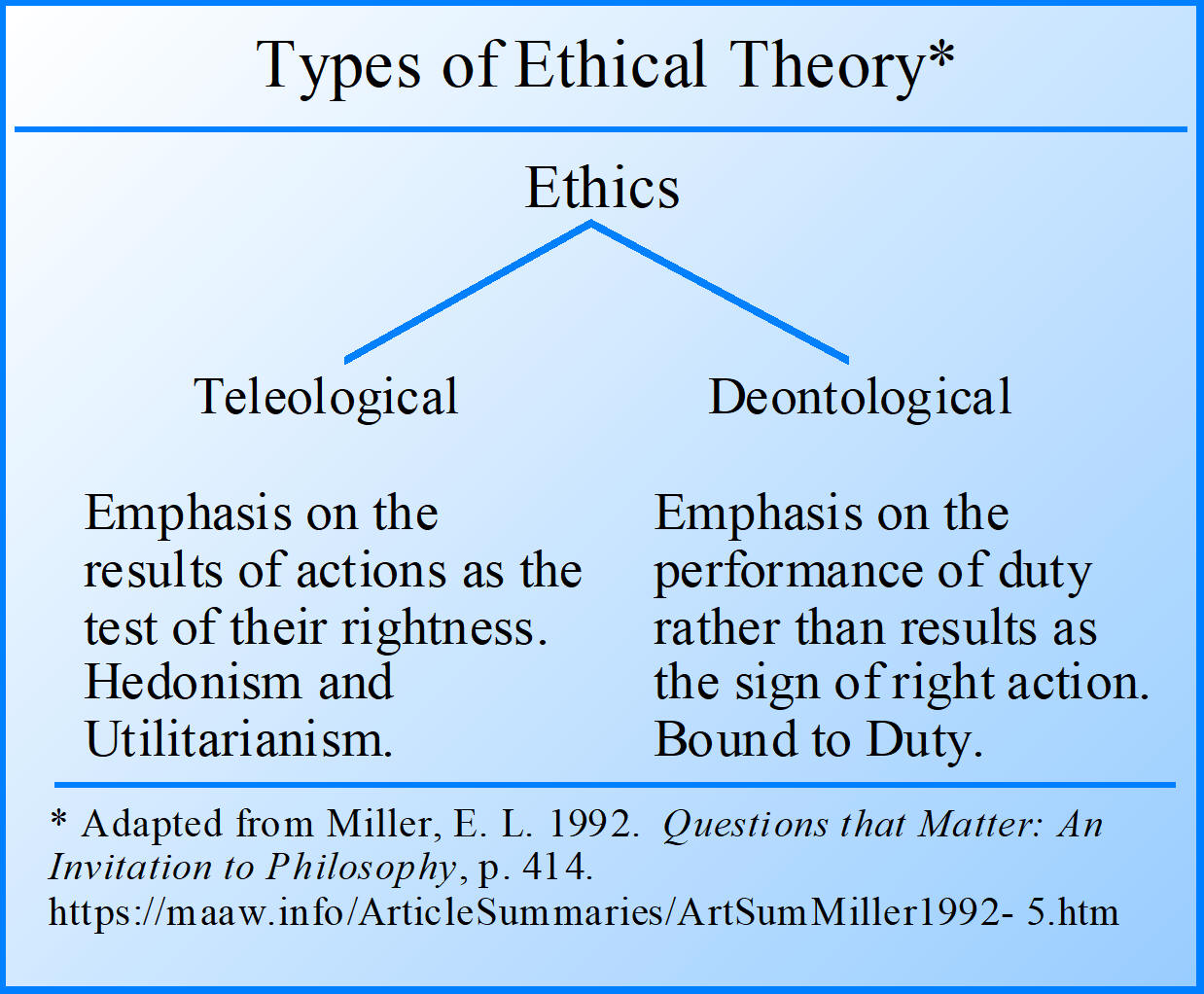

There are two types of ethical theory: teleological and deontological. Teleological theory stresses the consequences of actions as the test of whether they are right or wrong, moral or immoral, and includes hedonism and utilitarianism. Deontological theory is based on the view that the will is bound to duty, and conformance to duty determines whether an action is right or wrong, moral or immoral. This chapter considers hedonism. Chapter 18 considers utilitarianism, and Chapter 19 examines the most influential deontological theory of morality, i.e., the role of duty.

Hedonism: The Pleasure Principle

Hedonism views pleasure as "the highest good." According to the hedonistic pleasure principle, pleasure is the criterion of right action. However, there are different forms of hedonism related to different concepts of pleasure and how the question of "whose pleasure" is answered. Pleasure relates to various aspects of human sensations such as the satisfaction of needs, happiness, or the absence of physical and mental pain.

Egoistic Hedonism

Egoism makes the self the central concern. Psychological egoism is based on the idea that everyone by nature pursues his or her own self interests. Ethical egoism is the view that everyone should pursue his or her own interest as the criterion of right action. Combining ethical egoism and hedonism produces the concept of egoistic hedonism that dates back to the ancient Greek philosophies of Cyrenaicism (about 400 B.C.) and Epicureanism (300 B.C.). Cyrenaicism was most interested in the lower pleasures. Enjoy as much bodily pleasure as possible. Eat drink and be merry, for tomorrow you may die. Bodily pleasures are far better than mental pleasures, and bodily pains are far worse than mental pains.

Epicureanism is also a version of egoistic hedonism but places emphasis on the absence of pain, especially mental pain in the form of anguish and fear. The Epicurean idea of a life of pleasure is health of the body and peace of mind, tranquility or serenity. The advocates of this version of egoistic hedonism were repelled by the entanglements of sexual involvements, marriage, family life, and public or political life. Instead they viewed friendships and the intellectual delights of philosophizing, rather than the drunken orgy as the way to a pleasant life. In a letter to Menoecceus, Epicurus explained the idea as follows:

"...When, therefore, we maintain that pleasure is the end, we do not mean the pleasures of profligates and those that consist in sensuality, as is supposed by some who are either ignorant or disagree with us or do not understand, but freedom from pain in the body and from trouble in the mind. For it is not continuous drinking and revellings, nor the satisfaction of lusts, nor the enjoyment of fish and other luxuries of the wealthy table, which produce a pleasant life, but sober reasoning, searching out the motives for all choice and avoidance, and banishing mere opinions, to which are due the greatest disturbance of the spirit."

Does "Is" Mean "Ought"

Any form of teleological ethical theory is subject to the criticism provided in the form of a question: Can an ought be derived from an is? The criticism is essentially that moving from a factual judgment "everyone seeks pleasure" to a value judgment "pleasure is the highest good" is a naturalist fallacy. How can there be ideals if "what is" is "what ought to be?" How can we move from the observation that we are selfish to the conclusion that we should be selfish?

Egoism or Altruism?

Egoistic hedonism is one of the most widely practiced moral philosophies. However, ethical egoism and egoistic hedonism conflict with the principles of altruism that are embedded in our Western moral consciousness: e.g., "Do unto to others as you would have others do unto you." Although the psychological egoist views altruism as a hopeless ideal, what happens when one egoistic hedonist's pursuit of pleasure deprives another of his pleasure? In this case should all egoistic hedonist agree to act to ensure the pleasure of all? If so they would no longer be egoistic hedonists because they would have altered their concern from self to the common good. The idea of pursuing the common good leads us to the moral philosophy in the next chapter, utilitarianism.

Utilitarianism or social hedonism is another widely practiced moral philosophy, although the actual application of the criterion is often difficult. Think of a group of men sitting in a lifeboat about three hundred yards from a sinking ship. A desperate sailor is clinging to the side of the ship and screaming for help. The men in the lifeboat see him, but they do not move. They have been taught that a lifeboat must sit off at least three hundred yards to avoid being pulled under by a sinking ship. The sailor begs them to save him, but they do not move. It is a simple problem: Should several lives be jeopardized in an attempt to save one more?

What is Utilitarianism?

Utilitarianism employs the principle of utility to mean an action that promotes the greatest balance of good over evil, or pleasure over pain. Like egoistic hedonism it judges the rightness of an action by its production of pleasurable consequences. However, the utilitarian or social hedonist is motivated out of an interest for the greatest possible number of people rather than self-interest. Utilitarianism or social hedonism combines hedonism with the benevolence principle to produce the ethical doctrine that an action is right if, and only if, it promotes the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people. It is a philosophical perspective as well as a democratic political perspective that has been the basis for legislative social reforms, welfare movements, and egalitarian ideals.

Bentham's Version: Quantity Over Quality

Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) is the founder of modern utilitarianism. Bentham's process for making moral decisions includes the following steps:

1. Consider the various courses of action available.

2. Take into account all the people affected including yourself as only one of them, and calculate the pleasures and pains involved.

3. Then choose that course of action that will result in the greatest balance of pleasure over pain.

Calculating a pleasure involves measuring or weighing it in seven ways (Bentham's idea of hedonic calculus), i.e., it's intensity, duration, certainty, propinquity (how near at hand it is), fecundity (its ability to produce more pleasures), purity (its freedom from pain), and extent (number of people affected). Bentham's doctrine also included four sanctions or motivations for ethical behavior: nature, law, opinion, and God. His reasoning was that if we fail to do what we should, natural laws, civil laws, public opinion, and God will make it unpleasant for us, in this life or the next, or both.

Mill's Version: Quality Over Quantity

Although Bentham was the founder of modern utilitarianism, John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) is the most famous. Both Bentham and Mill agree on the principle of utility as augmented by the principle of benevolence. Actions are right if, and only if, they produce pleasure, happiness, or satisfaction of needs, and this is distributed among as many people as possible. They also were in agreement that the principles of social utilitarianism cannot be proved.

Mill did not agree with Bentham's purely quantitative view of pleasure. For example, Bentham indicated that the game of push-pin is of equal value with the arts and sciences of music and poetry. If the game of push-pin provides more pleasure, it is more valuable than either. Mill disagreed saying push-pin may be more fun than poetry, but it yields an inferior happiness. And can the joy of sex really compare with the joy of the intellect? Wouldn't you rather be a dissatisfied human than a satisfied pig. For Bentham "greatest happiness" meant most. For Mill it meant best.

Mill also differed with Bentham in the area of moral sanctions. He accepted Bentham's external sanctions (nature, law, opinion, and God), but added an internal sanction, i.e., a conscience, or subjective feeling in our minds that is the ultimate sanction or motivation of all moral behavior. However, Mill did not believe this internal sanction was innate, but instead acquired and cultivated.

Mill was a champion of liberal causes. For example, he advocated the abolition of child labor and slavery, and perfect equality in the area of women's rights. Mill wrote the following in his Subjection of Women (1869).

"That the principle which regulates the existing social relations between the two sexes - the legal subordination of one sex to the other - is wrong in itself, and now one of the chief hindrances to human improvement; and that it ought to be replaced by a principle of perfect equality; admitting no power or privilege on the one side, nor disability on the other."

In the first edition of Utilitarianism Mill said that the moral rightness of an action is independent of the motive behind it. A critic gave an example that involved a man who saved another man from drowning so that he might torture him to death. The critic asked how could this be a morally right action? In response to this criticism Mill added a footnote in the second edition explaining that the critic had confounded the very different ideas of motive and intention. The morality of an action depends entirely upon the intention.

Act-Utilitarianism/Rule-Utilitarianism

More recent philosophers distinguish between act-utilitarianism and rule-utilitarianism. For act-utilitarianism the question is, What action should be taken in this situation to bring about the greatest happiness for the greatest number? For rule-utilitarianism the questions is, What rule should be followed in a particular situation to bring about the greatest happiness for the greatest number? Mill seems to have advocated both when he said we cannot live without rules of conduct, but some situations are so singular and exceptional that they do not fall into any general category or under any general rule.

Some Objections

Although there are many objections to utilitarianism, five are mentioned as more significant than the others.

1. Utilitarianism is neither purely egoistic or altruistic because it tells us to distribute happiness to as many people as possible, but also tells us that we are one of those people. For critics, the question is whether Jesus, Socrates, or St. Francis would count himself as one?

2. There are many forms of hedonism, but how is it practical to measure, compare, and calculate what action would produce the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people?

3. The utilitarian numbers game is difficult to play. How do you distribute ten parts of happiness? Five parts to two people, two and a half parts to four people, one part to ten people?

4. Utilitarianism (and hedonism in general) is incompatible with the standards of morality that we actually use. For example, producing the greatest happiness for the greatest number may easily conflict with our concept of justice, e.g., frame one person to make ten other people happy.

5. Utilitarianism suffers from the same naturalistic fallacy as any other type of hedonism, i.e., attempting to derive an ought from an is. What have our natural masters, pain and pleasure got to do with what we ought to do? What does pleasure or the avoidance of pain have to do with what is desirable, or worthy of desire, or right?

After considering the theories in the previous chapters one might ask if there aren't some actions that are unconditionally right or wrong?

Morality as Unconditional

The teleological theories or morality presented in Chapters 17 and 18 emphasized intended consequences of actions as the criteria of rightness. The idea in egoistic hedonism is to promote personal pleasure. Utilitarianism is similar but the emphasis is the promotion of the general welfare. Deontological theory is based on the very different viewpoint that the consequences of our actions have nothing to do with their rightness or wrongness. In deontological theory the criterion of moral behavior is taking a certain action with the intent to perform one's duty.

In Foundations of the Metaphysics of Morals Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) regarded morality as a matter of ought, or obligation. For Kant, the moral ought is an unconditional ought because morality must be necessary and universal, and it must be absolutely binding on everyone. We should take the consequences of our actions into consideration in order to determine whether it is our duty. But we should act out of duty, not for the sake of the consequences.

Kant rejected all forms of naturalistic ethics, i.e., any theory that bases its ought on nature such as happiness, or the avoidance of pain. For Kant, happiness is an impossible basis for moral laws. Morality based on consequences distorts the ideal of morality. Genuine morality should be derived a priori from pure reason.

The Good Will

For Kant pleasure and happiness are gifts of nature, but they cannot be the foundation of morality. There are other innate gifts such as intelligence, wit, and courage, and accidental gifts of power, wealth, and honor. But these are not absolute goods. They have no intrinsic or unconditional value and can be corrupted and turned into an evil without the necessary and sufficient condition for all right action, the foundation of rational morality - the good will. By good will, Kant means an intention to act in accordance with moral law, and moral law is what it is no matter what anything else might be. To be really moral, we must act out of duty, i.e., with good will or with respect for the moral law.

Kant's Categorical Imperative

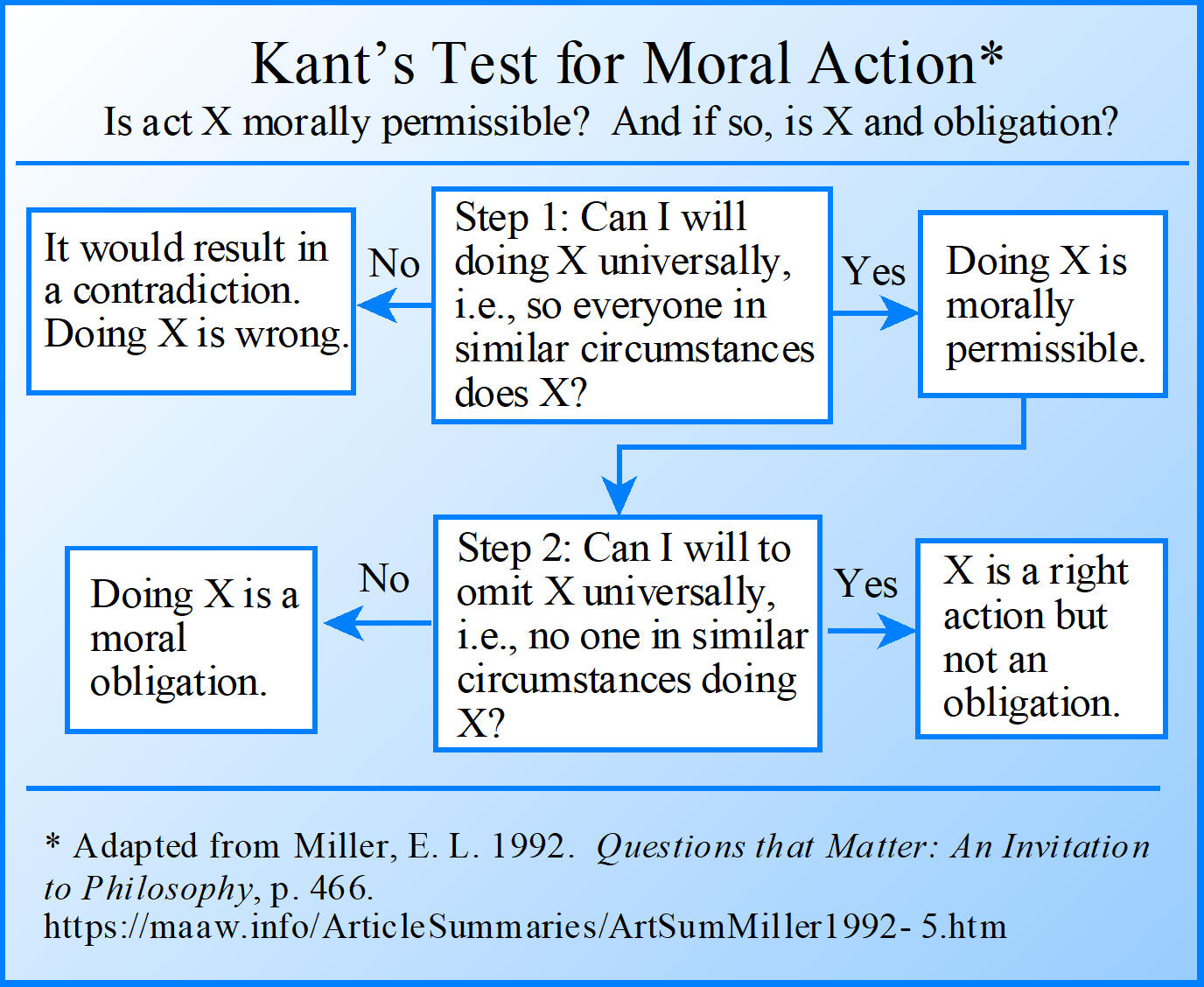

All imperatives are either hypothetical or categorical. Hypothetical imperatives command someone to do X if they want to achieve Y. Notice the hypothetical form, if X then Y. But a categorical imperative would command someone to do X because it is intrinsically right. Kant's categorical imperative is the fundamental principle of morality, or criterion to make sure our actions are motivated by good will and performed out of duty, i.e., moral. When you are about to take action X, ask yourself whether you can will that everyone else in similar circumstances act in the same way, i.e., universalize the act. If the answer is yes, you are acting out of duty or with good will. It is a categorical imperative because it is intrinsically right regardless of any other considerations, no ifs, no conditions, no strings attached. It is unconditional without regard to consequences or personal desires.

The Test of Moral Actions

According to Kant, when we make a moral judgment about a course of action we primarily need to consider the possibility of a contradiction in our action. Does universalizing the principle of my act result in a contradiction? If so, the action fails the test and must be rejected as immoral. For example, a man who makes the decision never to help others in need may himself need help in certain circumstances. By universalizing his decision he would rob himself of the aid he needs.

Some Objections

1. Kant assumes that there is a moral law, but he does not establish that there is an objective morality.

2. Kant also makes it clear that morality cannot be based on anything empirical or natural, but Mill, who followed Kant said morality must be based on nature.

3. Kant's distinction between the moral world and the natural world is also problematic because it downplays any moral responsibility we have for the natural world, e.g., environmental ethics and animal rights.

4. In addition, Kant's theory of morality appears to divide a person's inner life into different faculties with their own functions and powers (faculty psychology). Is it appropriate to assume that desires and inclinations are distinct from and subservient to the will, and the will is different from and subservient to reason?

5. Following Kant's theory we must always act out of a good will or duty, and there are no exceptions. For example, we always have to tell the truth no matter what! Really? What are you going to say when your spouse ask "Does this outfit make me look fat?"

6. Finally, the idea that the consequences of our actions are irrelevant for moral decisions and action is difficult if not impossible to accept as practical advice.

_______________________________

Go to the next Chapter: Chapter 20.

Note: In addition to their contributions to philosophy, both Jeremy Benthem and John Stuart Mill made significant contributions to economic theory. See Oser, J. 1963. The Evolution of Economic Thought. Chapter 8: The Classical School: Bentham, Say, Senior, and Mill. Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc. (Summary).

Related summaries:

Dawkins, R. 2008. The God Delusion. A Mariner Book, Houghton Mifflin Company. (Summary).

Hornsey, M. J. and K. S. Fielding. 2017. Attitude roots and Jiu Jitsu persuasion: Understanding and overcoming the motivated rejection of science. American Psychologist 72(5): 459-473. (Summary).

Kenrick, D. T., A. B. Cohen, S. L. Neuberg and R. B. Cialdini. 2018. The science of antiscience thinking. Scientific American (July): 36-41. (Summary).

Martin, M. and K. Augustine. 2015. The Myth of an Afterlife: The Case against Life After Death. Rowland & Littlefield Publishers. (Notes and Contents).

Prothero, S. 2007. Religious Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know - And Doesn't. Harper San Francisco. (Summary).