The Question of Knowledge: Summary of Chapters 8-11

Study Guide by James R. Martin, Ph.D., CMA

Professor Emeritus, University of South Florida

Chapters 1-2 |

Chapters 3-7 |

Chapters 12-15 |

Chapters 16-19 |

Chapters 20-22

The author considers three levels of skepticism in this chapter:

1. Common-sense skepticism - the tendency to avoid gullibility, superstition, and prejudice.

2. Philosophical skepticism - the tough-minded tendency to deny or doubt various philosophical claims, e.g., that everything has a cause, that the external world is as we perceive it to be, and that God exist.

3. Absolute skepticism - To deny the possibility of knowledge.

Although absolute skepticism is the main focus of this chapter, there is a short section on philosophical skeptics who are usually associated with terms like freethinker, atheist, unbeliever, and agnostic. All of these terms refer to someone who denies or doubts prevailing religious or philosophical doctrine. For example, an agnostic rejects a doctrine because of an underlying belief that human knowledge is incapable of determining whether the doctrine is true or false. An atheist, on the other hand denies the existence of God. Note that The Question of God is the focus of Part 3 of this book.

Absolute Skepticism: Pyrrho - The Classic Skeptic

The best example of absolute skepticism was provided around 300 B.C. by Pyrrho and his followers who taught that nothing is certain and the wise man would suspend judgment on all matters. Their position was based on ten modes of doubt:

1. The variety of animals - Different animals do not receive the same impressions from the same things. Their senses are different so will the impressions produced by them. For example, hawks are keen-sighted, dogs have an acute sense of smell.

2. The difference in human beings - Life in some ways can be injurious to one man but beneficial to another, so it follows that judgment must be suspended.

3. The different structure of the organs of sense - An apple appears green to the sight, sweet in taste, and fragrant in smell. An object of the same shape appears different by differences in the mirrors reflecting it. What it appears to be may be something else.

4. Differences in Circumstantial Conditions - Impressions differ on the basis of conditions and changes in a person's health, sleep, joy, sorrow, age and many other things.

5. Differences in Disciplines, Customs, Laws, and Dogmatic Convictions - Considerations of such things as good and bad, beautiful and ugly, true or false differ based on customs, laws, myths and dogmatic assumptions.

6. Intermixtures - Nothing appears pure in and by itself. Everything is different with different mixtures of light, moisture, solidity, heat, cold , movement etc.

7. Positions, Intervals and Locations - Things thought to be large appear to be small, square things round, straight things bent, colorless things colored. Everything must be observed from places and positions so their real nature is unknowable.

8. Quantities and Formations of the Underlying Objects - The quantity and quality of things changes their effect. Heat or cold, swiftness or slowness.

9. Frequency or Rarity of Occurrence - Things appear different depending on their frequency.

10. The Fact of Relativity - Things are perceived based on their position to something else. Relative things are in and by themselves unknowable. All things are relative to our mind.

Is Absolute Skepticism a Coherent Position?

Some objections to absolute skepticism include:

Some things at least are certain. 2 + 2 = 4.

The skeptics position that we cannot know anything actually means that we must know something.

The skeptics position that we cannot know anything is self-refuting. If we know nothing, we cannot know that we know nothing. If absolute skepticism is true, then it must be false.

Knowing is Not a Simple Matter

Knowing or knowledge includes at least three categories:

1. Knowledge as personal acquaintance, as in the statement, "I know Mike."

2. Knowledge as mastery of information or data, as in "I know Spanish."

3. Knowledge as in the claim that something is true, e.g., "I know in fourteen hundred and ninety-two Columbus sailed the ocean blue."

Epistemology, or the theory of knowledge is mainly concerned with problems stated as truth-claims.

If we reject absolute skepticism, the question becomes not whether we can know, but what, how, and how much we can know.

What is the basis of knowledge? How we answer that question is the basis for the rest of our philosophy.

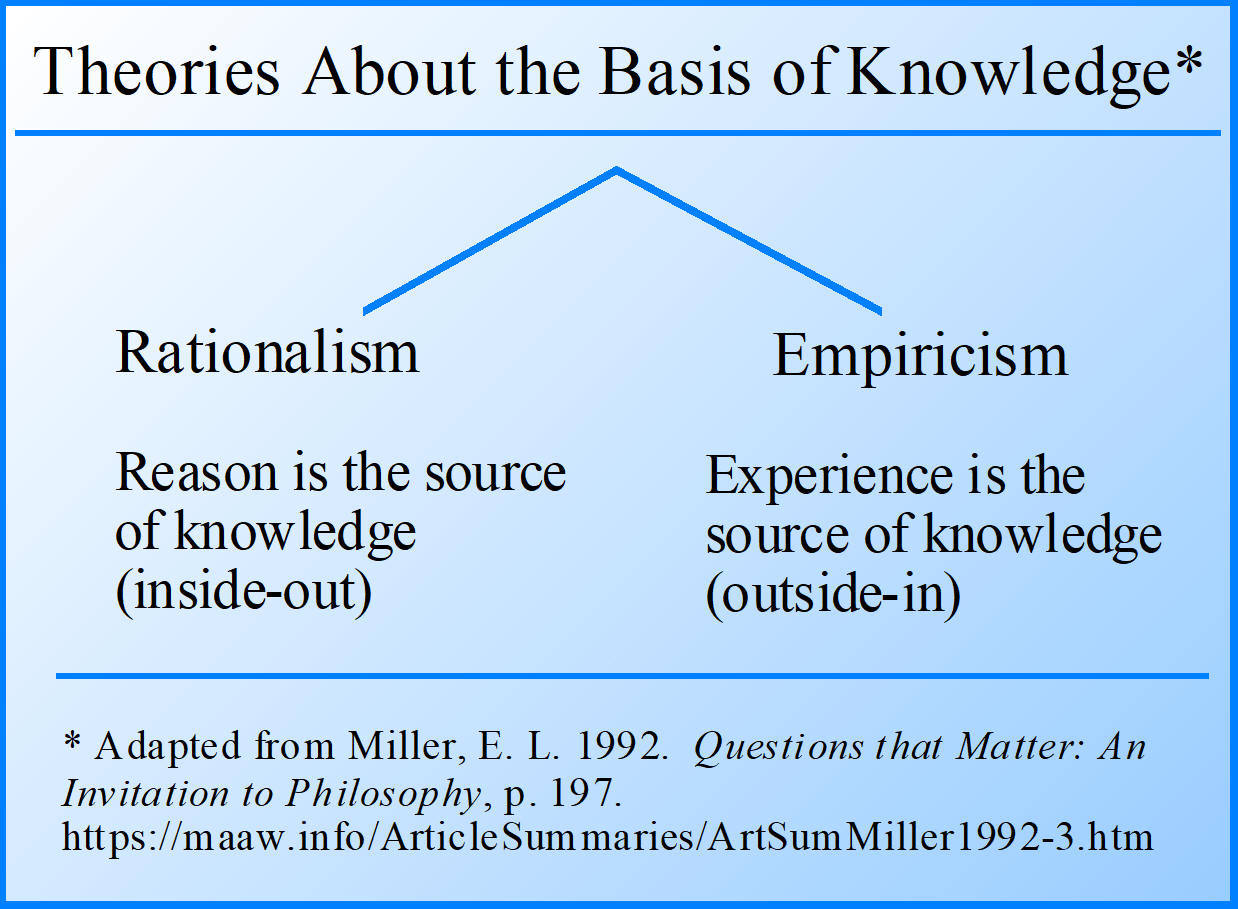

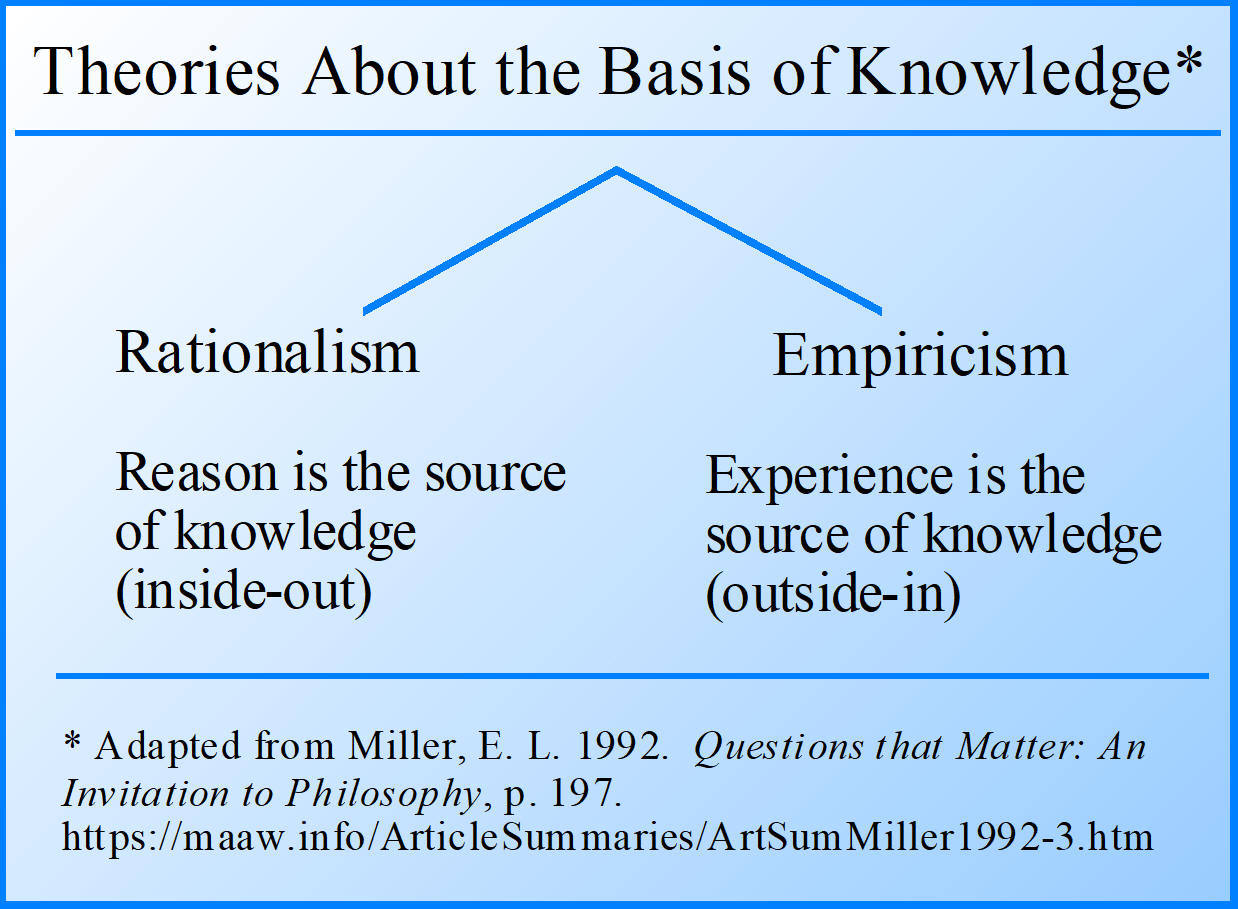

Two Main Theories About The Basis Of Knowledge

One theory places emphasis on reason as the source of knowledge (inside-out), while the other theory places emphasis on experience as the source of knowledge (outside-in). The theory stressing the intellect or reason is referred to as rationalism, and those who support this view are called rationalist. The theory that places emphasis on experience is referred to as empiricism, and those who support this view are called empiricists. Of course empiricists are also rational thinkers. In the loose sense all philosophers are rationalist in that they are interested in reasoning, reflecting, criticizing, and examining. However, it is in a strict more technical sense that the term rationalism is an epistemological theory or a theory about the basis of knowledge.

Reason As The Basis of Knowledge

Rationalism is the belief that at least some knowledge about reality (actual existing things) can be obtained through reason without any help from sense experience. The author provides two classic examples of rationalism: The rationalism of Plato, and the rationalism of Descartes.

The Rationalism of Plato

Plato viewed reason as the characteristic that separates humans from the lower animals. He argued that human happiness is obtained from contemplation and knowledge, but as long as we are in this world we are constrained from the attainment of knowledge by our bodily needs. We are slaves in its service. More importantly, our souls are imprisoned in our bodies and can only peer out through the five senses. Sense experience is a hindrance to real knowledge. Only when the soul is set free from the body by death can we enjoy absolute knowledge. Therefore, real philosophers do not fear death.

What little knowledge we acquire in this world is only possible because it is innate or inborn. Plato argues that we have knowledge of equality, beauty, goodness, uprightness, and holiness before birth. When we see something that appears similar to something else, but see that it is not equal, we must have had some previous knowledge of equality. Before we began to see and hear and use our senses we must have acquired the knowledge that there is a thing such as absolute equality.

The theory of innate ideas is not to be confused with instinct. Instinct is subcognitive and purely mechanistic behavior that enhances survival. Innate knowledge is built into the mind at birth. Plato contends that our innate knowledge supports the idea that the soul is immortal and exist both before birth and after death.

The Rationalism of Descartes

Descartes (1596-1650) developed a "geometrical method" for philosophy that he described in Rules for the Direction of the Mind. A man shall never assume what is false is true, never spend his mental efforts to no purpose, and will gradually increase his knowledge to understand all things. Descartes uses intuition to start with irreducible truths, and uses deduction to obtain more truths. His view of intuition is that it is an innate direct knowledge or awareness of something derived from the mind alone. Intuition enables us to expand our knowledge by deducing additional ideas and truths from our intuited ones.

A Contemporary Version: Chomsky

Noam Chomsky (1928-) argued that the phenomenon of language is impossible without innate intellectual structures. More specifically, there are certain universal principles inherent in all languages, or features that are not the result of learning, but are instead features that we are born with. From Chomsky's perspective there is no reason to doubt that what is true of language is true of other forms of human knowledge. (Chomsky, N. 1969. Language and the mind. In Readings in Psychology Today: pp. 282, 286).

There are some problems with Chomsky's theory. It is not clear how the mind acquires this innate structure in the first place. Chromsky says it is a complete mystery. Another question is what is the relation of this innate intellectual structure to truth? Are we to believe in some sort of pre-established harmony where our innate structure corresponds to reality? Or something like Plato's preexistence of the soul? This sort of question comes up again in Chapter 11.

Chapter 10: The Way of Experience

When philosophers emphasize experience as the source of knowledge they are referring to sense experience, i.e., perceptions derived from the five senses: sight, sound, touch, taste, and smell.

What is Empiricism?

Empiricism is the view that all knowledge of reality is obtained from experience. This means that the mind is a blank tablet at birth, and that anything written on the tablet is written by the five senses.

Classical Empiricism: Aristotle and St. Thomas

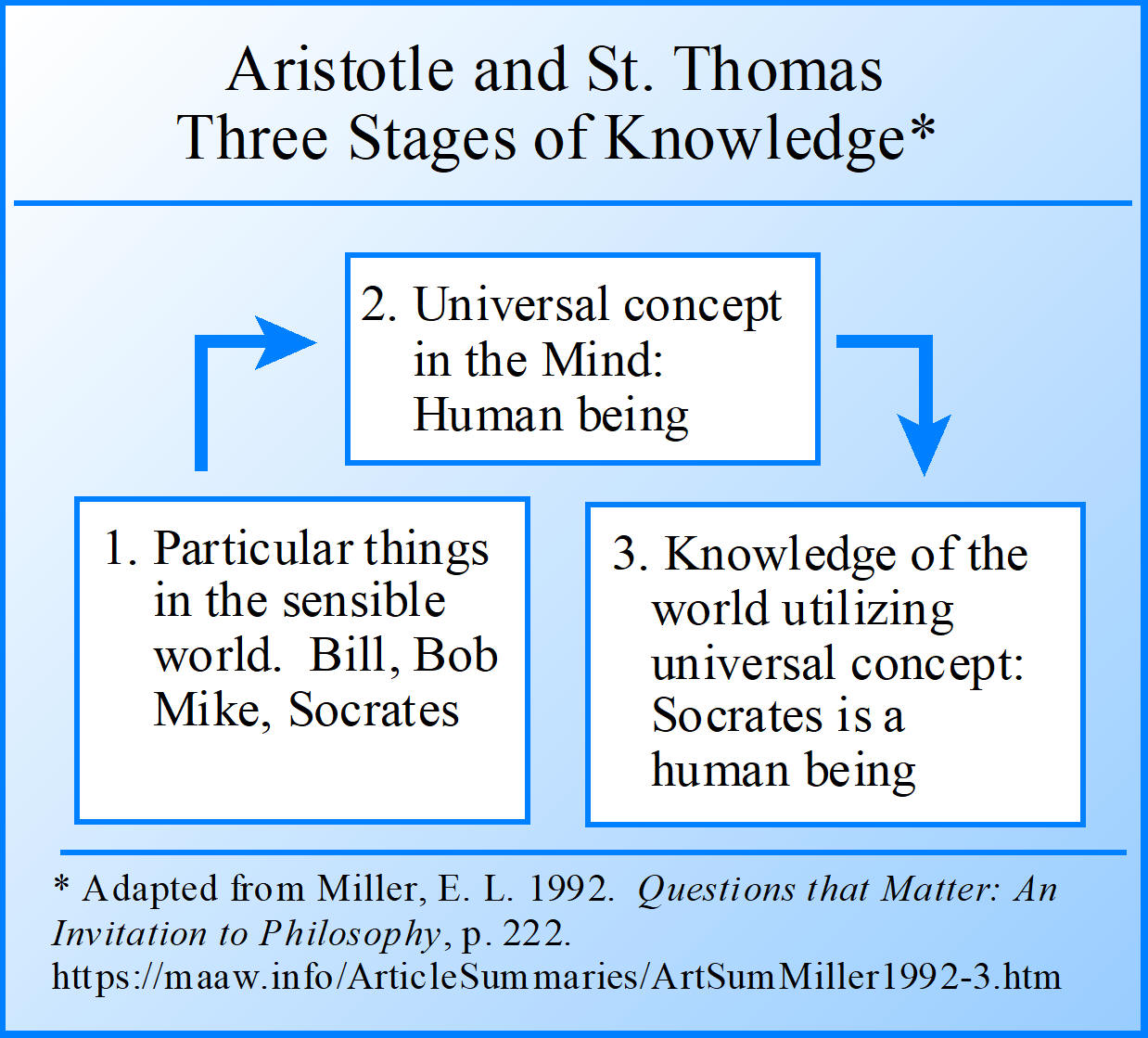

Aristotle, unlike Plato believed that knowledge is derived through our sense experience of specific things in the world. He agreed with Plato that knowledge involves general or universal ideas (man, chair, table, dog), but that this knowledge was built up in the mind through repeated experiences and induction. In this way they become the building blocks of reasoning. Universal ideas are neither innate, nor developed from higher states of knowledge, but instead are derived from sense-perception.

St. Thomas had the same empiricist idea and stated that nothing is in the intellect that was not first in the senses. Universal ideas are unlocked in the mind by abstraction, i.e., the mind is enabled to understand universal features from particular instances of things, and then ignore the particulars that are not essential to them. For example, after coming in contact with numerous people with various features, the mind grasped the universal idea of human being.

For both Aristotle and St. Thomas we derive universal concepts and principles from particular things we encounter in the world, and use those concepts to speak of them, think about them, and know them. These three stages are illustrated in the graphic below.

Modern Empiricism: Locke

John Locke (1632-1704) rejected the theory of innate ideas stating that the arguments in support of the theory do not prove it. Even if it were true that certain principles are universally agreed upon by all mankind, it would not prove that they are innate. Many universal principles are not known to a large part of mankind. In addition, it is evident that children and idiots have no apprehension or thought of them.

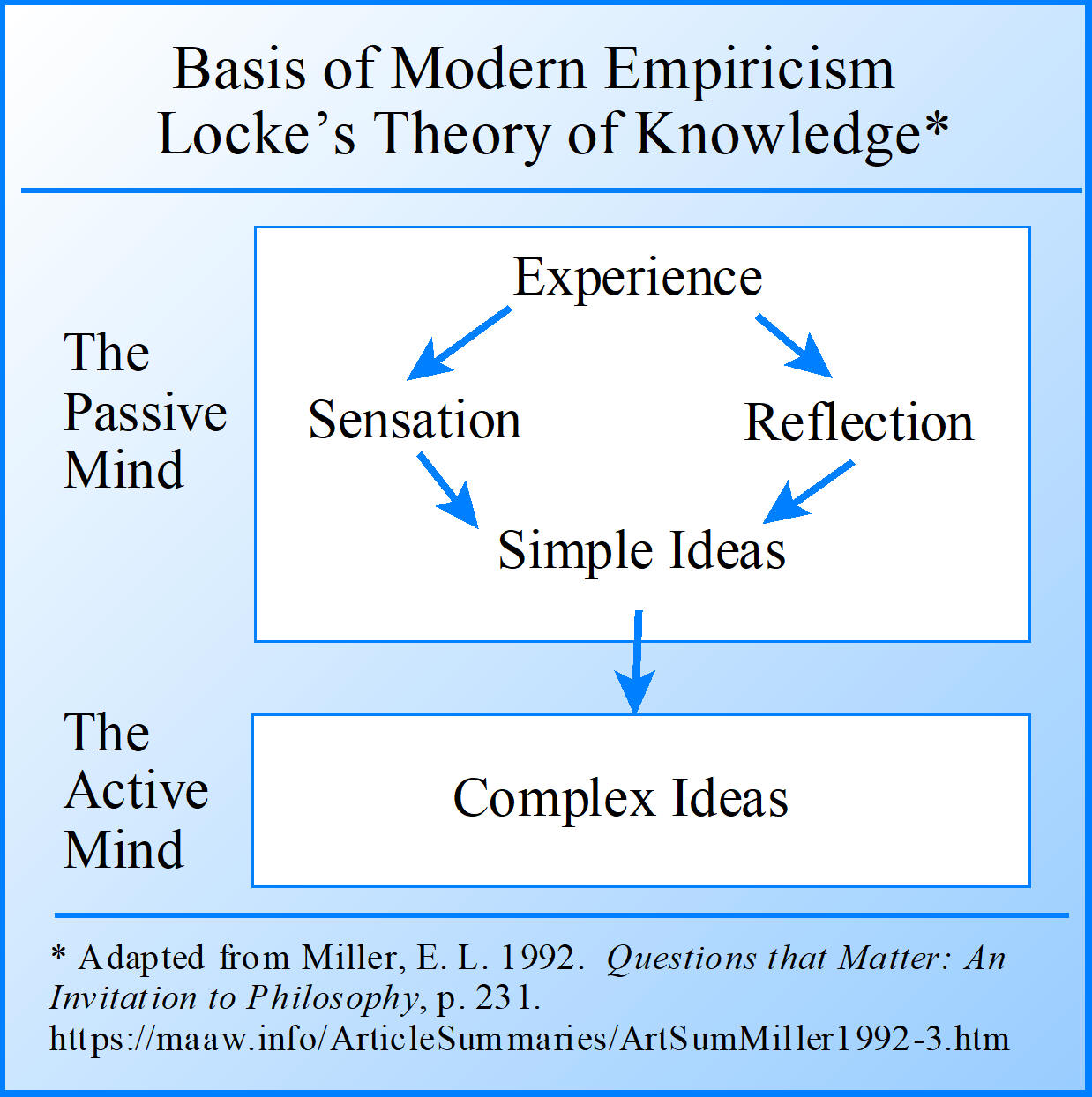

The origin of the ideas that exist in our minds is experience. Experience takes two forms, sensation and reflection. First, things in the external world enter our minds through sensation, e.g., red, yellow, hard, soft, hot, cold. Second, there is an internal experience or operation of our minds, or reflection, e.g., thinking, believing, doubting, comparing. These external and internal experiences are the only two ways that ideas are written on the blank tablets of our minds.

Sensation and reflection are the foundations of knowledge, but they are passive. The mind also has an active side where it constructs complex ideas out of simple ones by combining, comparing, and abstracting. There are three ways the mind exerts its power over simple ideas to form complex ideas.

1. The mind combines several simple ideas into one compound or complex idea.

2. The mind brings two simple or complex ideas together to obtain ideas of relationships.

3. The mind separates them from all other ideas in a process Locke referred to as abstraction.

Locke emphasized epistemological dualism, i.e., that there are two factors involved in knowing: the mind that does the knowing, and its ideas that are the known. But there is a third factor that includes the objects that are represented or known by means of our ideas. Representative perception is the theory that our ideas faithfully represent objects in the external world.

A problem with this theory (the egocentric predicament) is that if all we can directly know comes from our own ideas, how can we know whether our ideas correspond to anything out there in the external world? Berkeley solved this problem with the idealist view that objects or things are ideas. In other words, there is no material substance, only mental substance (see Chapter 6: Idealism).

Radical Empiricism: Hume

Locke believed in two basic substances, mind and matter. Berkeley followed Locke with the idealist philosophy that denied the existence of matter, leaving only mind and ideas. David Hume's (1711-1776) view of knowledge is similar to Locke's but is more extreme. According to Hume all we have are perceptions divided between impressions and ideas. Impressions are vivid sensations, while ideas are copies of impressions that provide the material for thinking. First we have sensations, then ideas that are based on these sensations. There is a mental substance that underlies our intellectual activities, and a material substance that underlies the external world. However, according to Hume there is no rational grounds for talk about matter or mind. Hume's position is called phenomenalism. It is essentially that all we can actually know is the phenomena or appearances that are presented to us in our perceptions. Material and mental substances are no more than bundles of perceptions. Hume is a philosophical skeptic in that he denies metaphysical principles and relations. There are only relations of ideas, and matters of fact.

1. Relations of ideas or matters of logic - These are certain but have no connection with reality, e.g., three times five is half of thirty.

2. Matters of fact - These are informative about the real world, but can never be certain because they are derived from limited perceptions, e.g., the sun will rise tomorrow.

Our ideas are either certain but uninformative, or they are informative, but never certain.

Chapter 11: The Problem of Certainty

The German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) disagreed with Hume saying that "I am certain of some of the truths which Hume called "matters of fact." His examples include the principle of causality, and Newton's Third Law of Motion (i.e., that all motion actions and reactions must always be equal). His theory supports the view that propositions can be both informative and certain. In this way Kant provides a theory of knowledge halfway between rationalism and empiricism.

Some Important Terminology

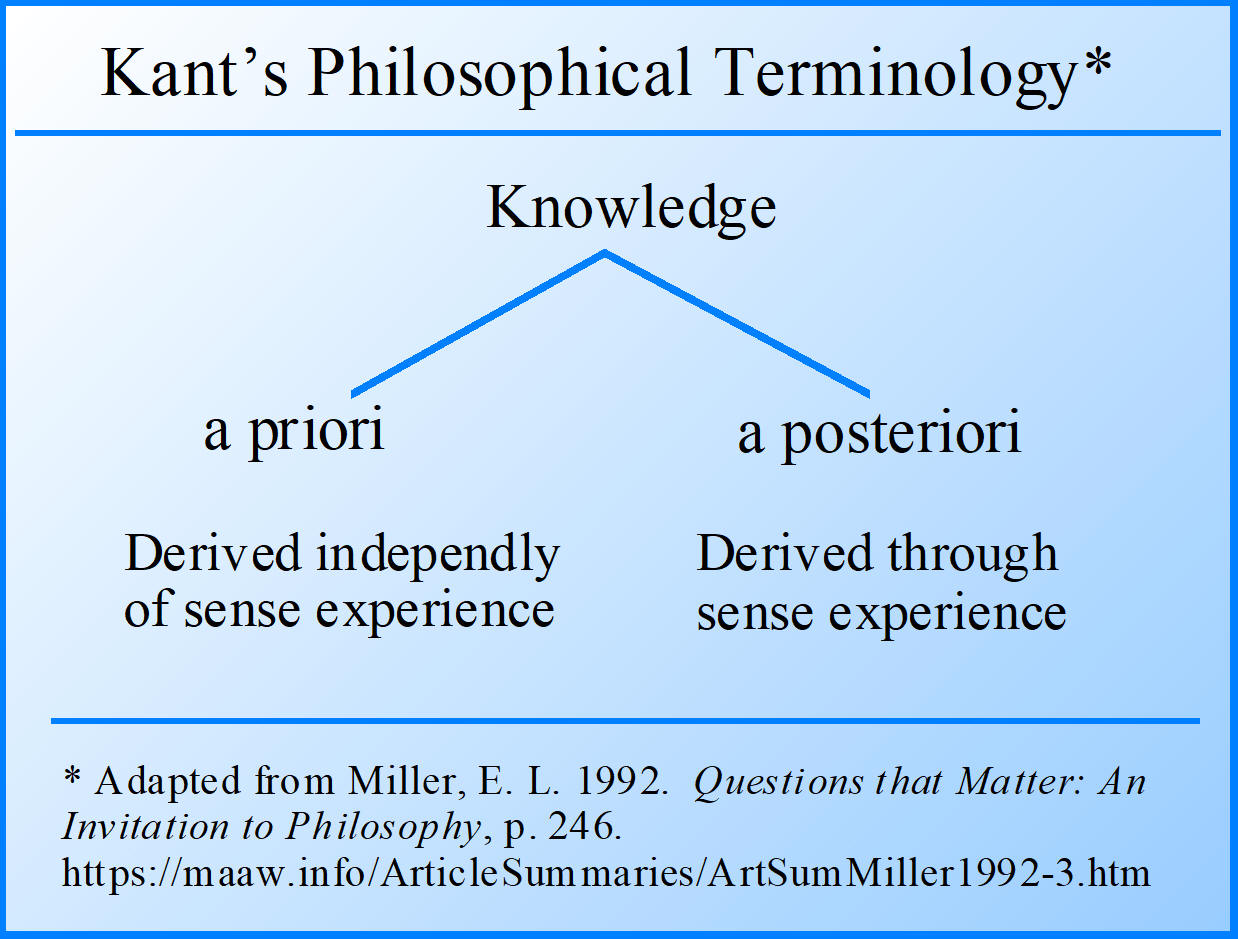

Kant made the distinction between two types of knowledge:

1. A priori knowledge (knowledge that comes before sense experience) and

2. A posteriori knowledge (knowledge that comes after sense experience).

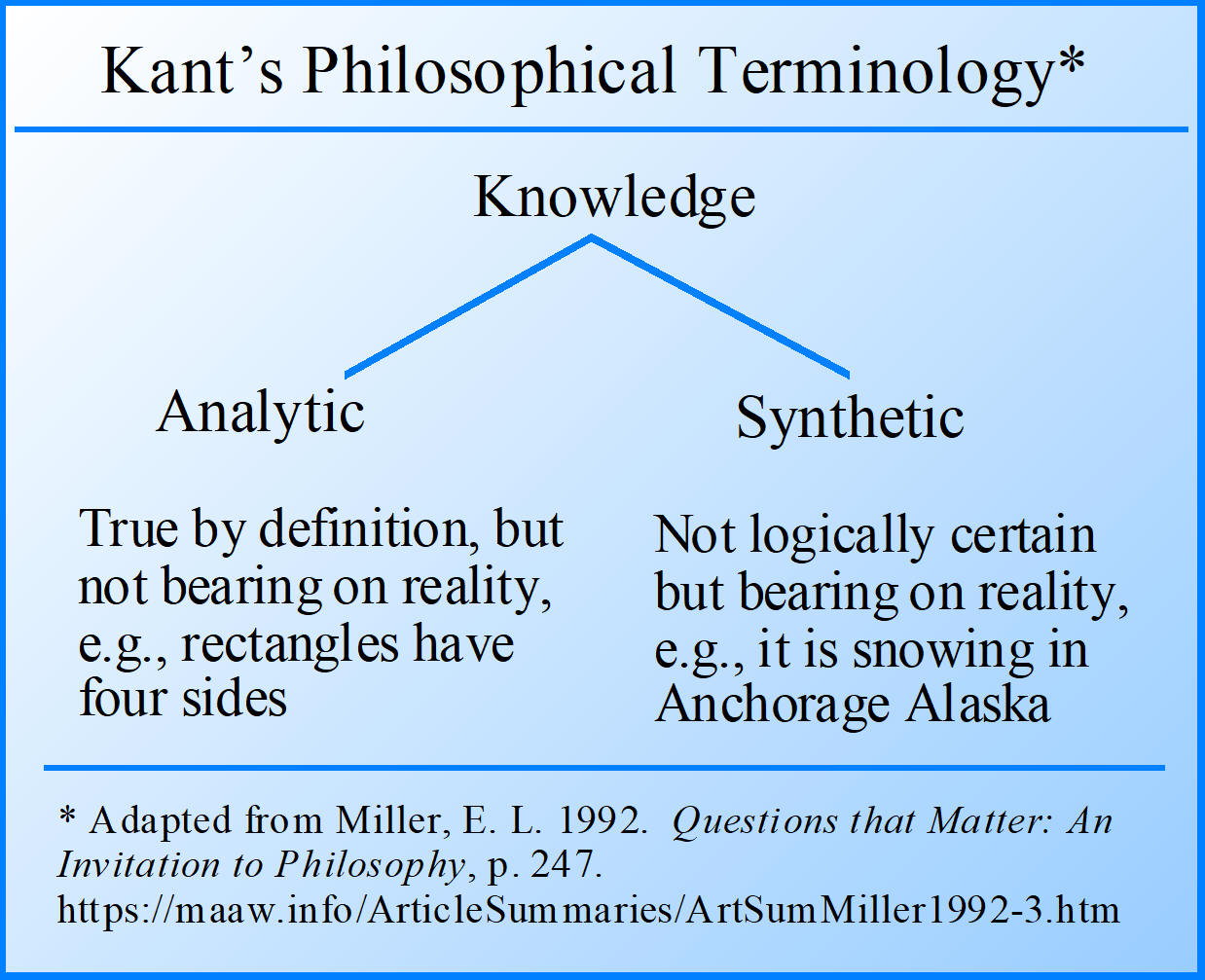

He also made the distinction between analytic and synthetic knowledge.

1. Analytic knowledge refers to Hume's relations of ideas or matters of logic (all barking dogs bark). These propositions are logically true or true by definition (sometimes called tautologies or redundancies), but tell us nothing about reality. They are a priori or independent of sense experience.

2. Synthetic knowledge refers to Hume's matters of fact where two ideas are synthesized in the proposition (Dogs bark, water freezes at 32 degrees Fahrenheit), and they tell us something about reality by either affirming or denying the existence of something.

Is There Synthetic A Priori Knowledge?

The real issue between rationalist and empiricists is whether we can possess any knowledge that is both a priori certain and synthetically informative? For Kant the answer is yes. Kant said, "I am certain of some of the truths which Hume called "matters of fact." He argued that ideas such as substance and causality are not obtained from experience, but are instead a priori categories of understanding that mold and shape our experience. Substance, causality, as well as space and time are a priori conditions of experience. In other words, they are pure concepts that do not come from experience, but instead experience comes from them.

In Critique of Pure Reason (1781) Kant made a distinction between empirical or a posteriori knowledge derived from sense experience, and pure or a priori knowledge that is completely independent of experience. Then he raises the question of whether pure knowledge exist, and establishes the two identifying marks that pure or a priori knowledge must have to be recognized: necessity and universality. He also distinguishes between analytic and synthetic propositions and explains that synthetic a priori knowledge is informative and bears the marks of necessity and universality not accounted for on the basis of experience.

Kant argues that all our knowledge begins with experience, but it does not follow that all knowledge arises from experience. So the question of whether there is knowledge independent of experience deserves closer investigation. Kant goes on to insist on the role of a priori concepts as conditions of experience. To know a thing as an object is only possible if we have intuition or perception of the object and a concept by which an object is thought of as corresponding to that intuition.

Kant also tells us that this category of a priori concepts that underlie understanding has no legitimate application beyond experience. This means as we have gained a priori certainty and universality for synthetic knowledge, we have given up any knowledge of reality beyond space and time. Our theoretical reasoning has proper application only to objects of possible experience. However, practical reasoning builds on the foundation of moral experience and provides a way to investigate knowledge of God, freedom, and immortality.

_____________________________

Go to the next Chapter: Chapter 12: God and the World

Related summaries:

Dawkins, R. 2008. The God Delusion. A Mariner Book, Houghton Mifflin Company. (Summary).

Martin, M. and K. Augustine. 2015. The Myth of an Afterlife: The Case against Life After Death. Rowland & Littlefield Publishers. (Notes and Contents).